Charlotte is planning a new vision for center city. How’d we do on the last one?

Charlotte is a city that loves big plans and heady visions. And since the 1960s, making a new plan for the city’s center has been the most regularly repeated tradition in Charlotte planning.

The Oddell Plan, adopted in 1966, set the stage, and new visions have been laid out and adopted every 10 years since, starting in 1980. Last week, Charlotte Center City Partners formally kicked off their next planning effort, meant to guide the development of uptown, South End and the neighborhoods just west of Charlotte for the next two decades.

“It’s a 50-year tradition. It’s been a highly effective way for us to inspire and provide a blueprint for growth,” said Michael Smith, CEO of Center City Partners. The planning effort, chaired by Johnson C. Smith University president Clay Armbrister and Wray Ward president and chief creative officer Jennifer Appleby, is expected to take about 18 months.

The vision plans for Charlotte’s center are meant to be aspirational, but much of what’s been proposed in past plans has actually come to pass. For example, the Oddell Plan called for a downtown stadium, more signature parks, and keeping the banks in downtown skyscrapers rather than decamping to the suburbs. City boosters at the time were clearly worried about the downtown core, as evidenced by this special, half-hour program produced on WBTV:

Other parts of that original vision haven’t happened (A downtown zoo, or burying vehicular traffic on Trade Street to turn it into a pedestrian promenade, anyone?). But the tradition of planning for a bigger future has been carried on.

Armbrister said the first meeting of the 32-member steering committee has already shown that people are thinking big about what the next vision could include.

“The group of people we have together are thinking big,” said Armbrister. “Just one little tease – someone said a lot of exciting cities often have waterways that run through them…You never know.”

The most recent vision plan, for 2020, was adopted in 2011. Charlotte’s center city is wrapping up what, by some measures, is its most explosive decade of growth. Center City Partners’ statistics show that between 2010 and 2019, there were 6.1 million square feet of office space, 2,203 hotel rooms and 11,624 new residential units constructed – the most in a single decade for each category.

“When I look at the last decade, it’s largely defined by growth and the maturation of our center city,” said Smith.

With 2020 fast approaching, we took a look at the current 184-page vision plan – where Charlotte succeeded, what fell short, what came to pass and what there’s still room to do.

What the 2020 plan foresaw

Growth on Stonewall, and around new parks

The two parts of uptown that have been transformed the most completely since 2010 are the Stonewall Street corridor and the Third Ward area including BB&T Ballpark and Romare Bearden Park. The 2020 plan predicted those areas would boom.

“The sale and development of the public land in the Stonewall/I-277 Focus Area will be a crucial barometer that signals the revving up of Center City’s nearterm development horizon,” the plan said.

It’s worth remembering how different those were less than a decade ago. The site where the ballpark and Romare Bearden are located was a mud, gravel and grass lot, as well as an old warehouse. And the south side of Stonewall Street was an empty patchwork of leftover land from realigning the I-277 ramps, along with the former Charlotte Observer building.

More people living uptown and in South End

Not too long ago, uptown was mainly a 9-to-5 district populated by workers, not residents, and South End was a post-industrial area with a lot of empty factories and warehouses. But the population of uptown and South End has grown massively, from 14,630 in 2009 to just under 30,000 in 2019.

“Center City’s recent population growth has been facilitated by public and private sector efforts to bring substantial residential development and employment to the core. It has also been supported by a growing national trend toward living in downtowns and dense urban settings,” the report noted, of a trend that has certainly continued.

Increased transit options

With the opening of the Blue Line extension to UNC Charlotte in 2017, and the pending, though delayed, opening of the Gold Line streetcar from Beatties Ford Road to Central Avenue, some of the key transit recommendations in the 2020 plan have been fulfilled.

Others, such as a light rail connection to the airport and some kind of rapid transit to the northern towns, are planned as part of the Charlotte Area Transit System’s 2030 plan. As CATS, the city and the surrounding counties look to plan and fund additional transit lines, this will remain one of the key focuses in the region for decades to come.

What didn’t come to pass – but would still be good ideas

Putting a cap over 277

One of the most ambitious ideas in the 2020 vision plan was capping part of the 277 loop, which often functions as a moat around uptown. That would effectively bury part of the loop and replace it with developable, connected, land. The ideal has floated around for decades.

“I-277 is a barrier between Uptown, South End and surrounding neighborhoods,” the report noted. “A cap over the loop should be constructed in phases and eventually stretch between Church Street and the LYNX Blue Line light rail. This strategy— introduced in the 2010 Vision Plan and built upon here—would help break down the barrier of the loop, create taxable property, and encourage infill development in Uptown and South End. The cap should include a large civic space framed by new private development.”

Obviously, that hasn’t happened yet. But it could be a transformative – though expensive – change for uptown and the surrounding neighborhoods.

Conceptual design of I-277 cap and development. Source: 2020 Vision Plan.

Creating pedestrian and bike loops around uptown

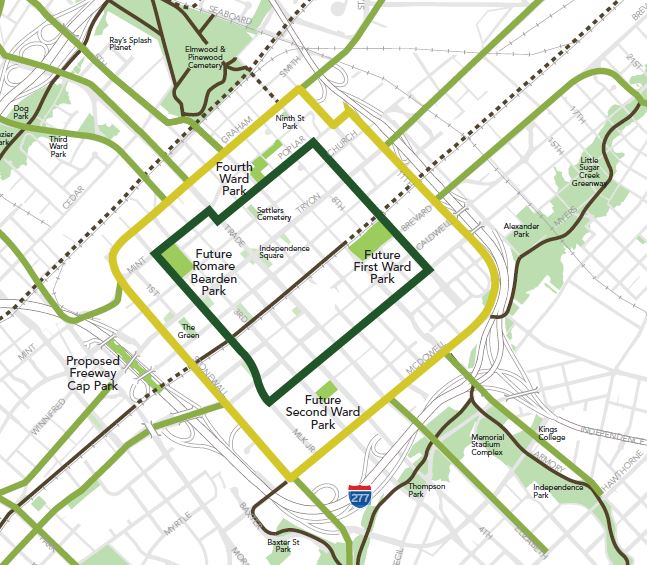

One of the big ideas for improving connectivity was to create two concentric loops, the Ward Loop and the Boulevard Loop, for bicyclists and walkers.

“A Ward Loop and Boulevard Loop will link existing and future ward parks in Uptown,” the report noted. “Linking the four wards of Uptown via special pedestrian- and bicycle-oriented design…would be a unique,

integrating feature of the park and recreation system.”

Charlotte got its first protected bicycle lane earlier this year – a 1.5-mile stretch along Sixth Street. But uptown remains far from having a dedicated, distinctively designed loop system like the one imagined, with “grand tree-lined boulevards” and “great pedestrian amenities” along its whole length.

Hypothetical map of Boulevard (yellow) and Ward (green) loops.

Developing a “grand structure”

“The great cities of the world have an easily recognizable structure—a building, bridge, gateway or other prominent architectural feature—that is synonymous with that place,” the 2020 vision plan noted. “Center City could position itself as a destination nationally and internationally with the development of such a structure.”

We still don’t have such a structure – but creating one could go a long way towards rebutting the common complaint that Charlotte’s appearance tends towards beige. The Charlotte Space Needle, Charlotte Arch or Charlotte Eye? Each has a ring to it.

Curveballs

Uber, Lyft, scooters

As with any vision plan looking ahead a decade, there are things no one saw coming. The biggest unforeseen hole in the 2020 plan is probably the impact of new ways to get around. When the plan was being written, Uber was brand-new and Lyft was still two years from being formed. The arrival in e-scooters was nearly a decade away.

Now, Uber and Lyft are ubiquitous – and, some advocates worry, contributing to traffic in cities and siphoning riders away from transit. Design regulations have had to keep up with new trends such as ride-hailing drop-off and pick-up locations, and Charlotte City Council spent months wrangling with e-scooter rules.

Smith said the new plan will have to contemplate the ongoing impact of ride-hailing apps and scooters, as well as the future effects of new technology like autonomous vehicles. Such disruptive technology could have effects beyond how we get around, such as drastically lowering the amount of parking required in dense parts of the city.

“The level of transportation disruption that we’re experiencing now and will experience,” he said, is probably the most disruptive since “back to the days of horse-drawn carriages and automobiles.”

New redevelopment sites opening

Although the 2020 plan predicted the filling in of parking lots and other vacant land uptown, intense redevelopment pressure has also occurred, wiping out old buildings and creating new developments in places planners didn’t foresee. The biggest example is the former Charlotte Observer site at Stonewall and Tryon streets, sold in 2016. There, 10 acres once home to a printing press and newspaper buildings are being redeveloped into by a five-million square-foot mixed-use development anchored by new office towers from Lincoln Harris.

Growth of South End as an office market

Reading the 2020 vision plan, it’s clear that South End was largely seen as an arts-and-design district with a growing retail and residential base. Some of the main recommendations for the area were to attract an art and design school and cultivate thearea as an arts destination.

“A new art and design school recruited to locate in South End will create a more vibrant design and innovation district. The school will complement existing creative firms, galleries and design studios,” the 2020 vision plan predicted.

But Class A office development has become one of the driving factors – if not the dominant factor – in South End’s recent development, as more staid companies embrace the creative office trend and look to attract millennial, white-collar workers who don’t want to drive to suburban office parks. Lowe’s, EY, Dimensional Fund Advisors and LendingTree are all anchoring major new projects, bringing thousands of corporate workers and reshaping the skyline. South End already totals 2.7 million square feet of office space, according to Charlotte Center City Partners, much of it built in the past five years. When the wave of new projects is complete, South End will total 4.1 million square feet of office space – roughly the equivalent of Ballantyne Corporate Park.