Charlotte is ‘on the cusp’ of its first true regional transit plan

The Charlotte region is taking concrete steps towards building a regional transit system that crosses county lines, but plenty of big questions remain.

Chief among them: Who will pay?

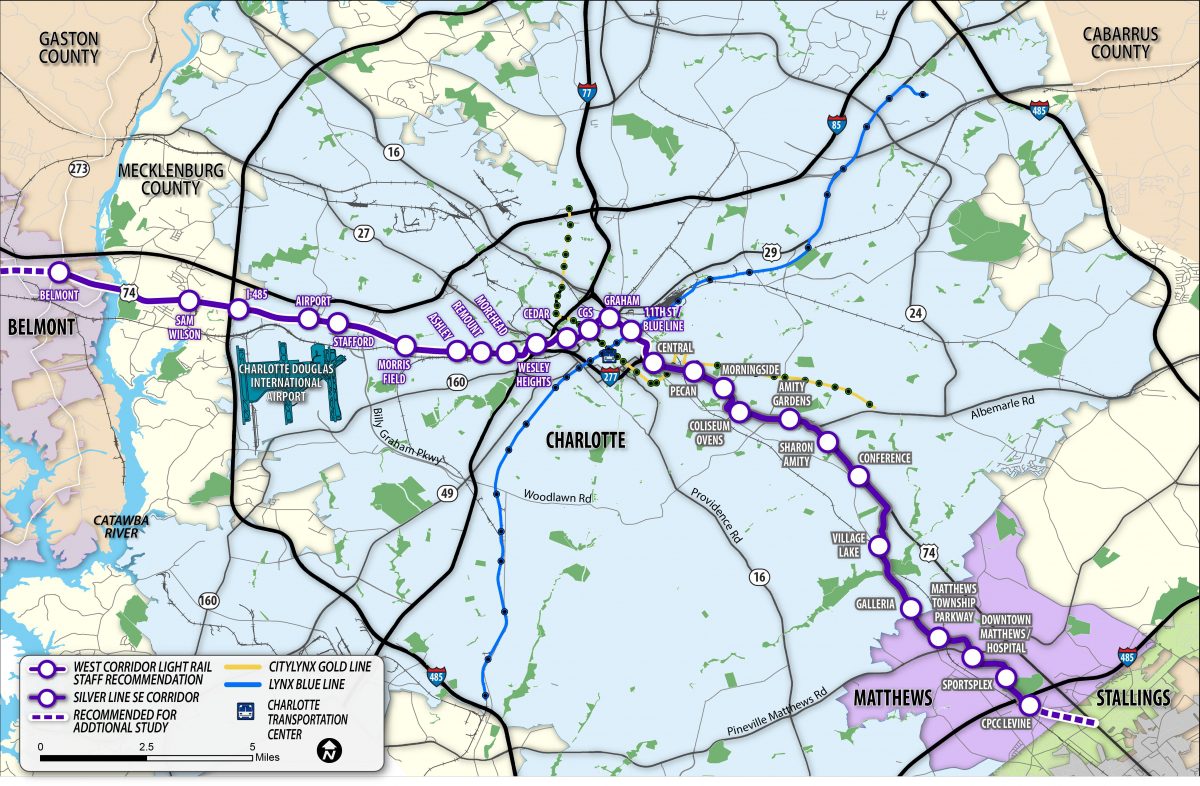

Charlotte Area Transit System planners are starting design work on the Silver Line. The new light rail will potentially run from Stallings through Matthews, around uptown Charlotte, past the airport and across the Catawba River to Belmont. That would mean one line crossing Union, Mecklenburg and Gaston counties – a first for the light rail system. In recent months, local governments from Indian Trail to Gastonia have passed resolutions in support of the plan and asked for light rail to their communities.

The Blue Line light rail, which was funded by a combination of a half-cent sales tax in Mecklenburg County, contributions from the state of North Carolina, and the federal government. Photo: Nancy Pierce.

Meanwhile, the Centralina Council of Governments is crafting a regional transit “vision” that’s expected to guide the broader plans going forward. And staff-level meetings have increased between transportation planners on opposite sides of the Gaston-Mecklenburg line.

“It’s a very big deal,” said Ron Tober, CATS’ first chief executive. He’s now a transit consultant. Tober called the proposed three-county route for the Silver Line, which is supposed to open by 2030, “monumental” at a meeting several months ago of the CATS governing board.

“I think we’re on the cusp of discussions that could lead to a regional transit authority,” said Tober.

But most of the discussions underway are still just that – discussions. CATS’ budget includes $18 million to bring the Silver Line up to 15 percent design. After that, funding from other counties and municipalities would likely be required to pay for more detailed design work, and eventually, construction.

Building the Silver Line could cost up to $8 billion, though a detailed estimate hasn’t been made. While Mecklenburg levies a half-cent sales tax to fund transit, Union and Gaston voters would likely have to approve additional taxes in those counties to help fund the new line.

“That will be a triggering event,” Tober said, of the moment voters in other counties are asked to chip in money.

Still, local officials say any collaboration is a positive in a region where transportation planning remains divided among an alphabet soup of agencies. In addition to the municipalities and counties around Charlotte and Mecklenburg, three NC Department of Transportation divisions oversee crucial highways and bridges in the area.

The proposed Silver Line alignment. Source: CATS

Then there’s the Charlotte Regional Transportation Planning Organization (CRTPO) for Union, Mecklenburg and Iredell counties, the Gaston-Cleveland-Lincoln Metropolitan Planning Organization (GCLMPO) and the Cabarrus-Rowan Metropolitan Planning Organization (CRMPO). Throw in CATS’ governing board, the Metropolitan Transit Commission (MTC), and the various other agencies just over the border in South Carolina, and it’s easy to see why regionalism sometimes gets more lip service than real policy-making muscle.

“It can get politically kind of byzantine,” said Tony Lathrop, a Charlotte-based attorney and member of the N.C. Board of Transportation. “But the economy doesn’t particularly pay attention to all those barriers. I’m not thinking, ‘Gosh, I’m crossing into the Cabarrus-Rowan MPO.”

Lathrop said he’s given a half-dozen presentations on regional transportation planning and the need for greater collaboration in the past couple months, to groups in Mecklenburg and the surrounding counties. He said he’s seeing enthusiasm grow for a regional transit plan as traffic worsens on the highways.

“You can’t build your way out of rush-hour congestion in a growing city,” said Lathrop. “I think that because of the trends and what’s actually happening on the ground, people are realizing that it’s real now.”

The GCLMPO last year unanimously passed a resolution of support for bringing light rail into downtown Gastonia. At a January meeting of the MTC, Randi Gates, principal transportation planner for Gastonia, said it would help the city, as well as more than 25,000 commuters who drive over the Catawba to Charlotte daily.

“This is, really, important to the city of Gastonia and all the communities within the Gaston-Cleveland-Lincoln MPO area,” said Gates. “We can only add so many lanes to existing highways, I-85 or US 74, so it’s critical that we have other options.”

Kings Mountain mayor Scott Neisler has been pushing for commuter rail to Charlotte, along the Norfolk Southern tracks that are currently used for freight. Neisler, chair of the GCLMPO, said the region needs to look ahead and start planning together, including consideration of a regional board of some kind to govern transit systems.

“It’s time now to think about 2040, 2050,” said Neisler. “It would probably operate better if we had a regional transit authority…We’ve got to plan, plan, plan.”

Building a regional vision

Tober said that more regional leaders participated in the MTC when the group was initially formed, after Mecklenburg voters first approved the county’s half-cent sales tax in 1998. But the regional members hold non-voting seats, and Tober said their participation fell off as the agency’s focus remained on the Charlotte-centric bus system and Blue Line.

Meanwhile, the goal of some kind of unified, regional approach to transit remained on the distant horizon.

“Someday, we’d have to have a regional transit authority, but it was a long time in the future,” said Tober.

For more than a year, the Centralina Council of Governments has been leading a regional planning effort. Michelle Nance convened more than 30 meetings of economic developers, government officials and businesspeople from eight different counties. She said she’s been pleasantly surprised by how many leaders in the region were eager to talk about transit, instead of just more highways.

“People were like, ‘We really need a vision,’” said Nance. “We wanted it to come from the region. It was very important that it wasn’t an idea from CATS.”

Over the next 18 months, the CCOG plans turn those initial talks into a concrete, regional vision. The group is seeking to raise about $3 million in funding from local governments and private organizations to continue the planning effort.

Who pays, and who calls the shots?

And that gets to the heart of the biggest questions about a regional transit system: Who will pay for it, and how would it be governed?

“The tensions arise when there’s not enough money,” said Lathrop. “Then you start having to make hard decisions.”

The federal government paid for 50 percent of the Blue Line and Blue Line extension (which totaled about $1.6 billion), as it does for most major transit projects. The state kicked in another 25 percent. But funding for transit from the state and federal government is more uncertain than in years past, and local officials have said any future expansions will likely require more local dollars.

“A regional transit plan will include regional funding discussions,” said Ajonelle Poole, a CATS spokesperson.

The Blue Line in Charlotte. Photo: Nancy Pierce

Mecklenburg’s half-cent sales tax raised $103 million for CATS in 2018 – not enough to fund the ambitious Silver Line expansion. Union and Gaston counties could activate local sales tax options to pick up some of the bill – if voters approve.

Denver Regional Transit District’s 1 percent sales tax – which applies in eight contiguous counties – remains the premier example of collective funding for a rail system. But Voters in the Southeast have shown they won’t always approve new transit spending.

Last year, Nashville voters rejected a referendum to raise taxes for a new light rail system, while Gwinnett County voters outside Atlanta shot down a referendum in March to expand the MARTA system. And the scuttling of the Durham-Orange Light Rail Transit, after Duke University refused to sign off on the proposed route, shows how one intransigent player can bring down a regional plan.

Nance said that rather than immediately tackling a 30-year plan, different jurisdictions can start by tackling “low-hanging fruit,” such as establishing a regional fare card that works across multiple counties. That could build trust between agencies that haven’t worked together in the past.

Tober said he thinks the region is still several years away from concrete planning for a regionally funded transit system with a new governing structure. That’s when discussions might get more difficult, Tober predicted.

“It’s real easy for things to go off rails when you start talking about where the money’s going to come from and who’s responsible for it,” he said.