Kron sisters’ botanical explorations left an important legacy

This article first appeared in the spring 2000 issue of “The LandMark,” the newsletter of The LandTrust for Central North Carolina. It is reprinted with permission of the author and the LandTrust.

When European explorers and colonists, African slaves and their descendants were discovering and settling America, they confronted a vast, unknown wilderness. Trying to understand the New World’s enormous variety, students of natural history described and classified American plants and animals using the binomial system invented in 1735 by the Swedish botanist, Carolus Linnaeus. Professional naturalists from outside North Carolina, like John and William Bartram and Andre Michaux, began to systematically catalogue North Carolina’s native flora in the late colonial and early national periods. Other North Carolinians of a scientific bent would extend botanical knowledge of native plants throughout the antebellum era. By the 1830s, amateurs drawn from the state’s educated class were enjoying botany as a hobby. Adelaide and Elizabeth Kron were two amateur botanists who lived in Stanly County for the last three quarters of the 19th century.

[highlight] From Paris to backcountry Stanly County, the Kron family tale [/highlight]

The Kron sisters were born in Montgomery County—Adelaide in 1828 and Elizabeth in 1831—and settled with their parents on a homestead that stands today, reconstructed on its original site, in Morrow Mountain State Park near Albemarle.

Their father, Dr. Francis J. Kron, and mother, Mary Catherine Delamonthe Kron, were from Trier, Prussia, and Tours, France. Francis Kron was a distinguished physician and outstanding horticulturalist. Not surprisingly, Adelaide and Elizabeth displayed a refinement and literacy that reflected their upbringing and education at St. Mary’s School in Raleigh. There were abundant opportunities for the young ladies to “botanize” around their home near the Great Falls of the Yadkin in the Uwharrie mountains. In 1847, still in their teens, they wrote to a friend revealing the joy and adventure of the pursuit.

“You are not mistaken in thinking that we love flowers, and as we have a few exotics our whole time is not bestowed upon wildflowers, though there are some of them which would do honor to the finest gardens; but you know that it is sufficient for a thing to be wild in order to be disregarded. If you were here among the labyrinths of our hills, you would relish Botany much more, for you would have the pleasure of climbing steep craggy rocks to get at your specimens; just imagine some very pretty flower hanging on the very edge of some high rock. You have a great desire to get the flower, and yet to obtain it you must put all your resolution, agility, and skill in climbing, to the test, before you can reach it, and when you have succeeded it seems almost like a victory, and a bloodless victory too, as far as others are concerned, though you may get a scratch or two yourself. And suppose that this lovely plant which you so arduously obtained is a non descript! What glory would it not be to immortalize your own sweet name in the annals of Botany by bestowing it on this flower?”

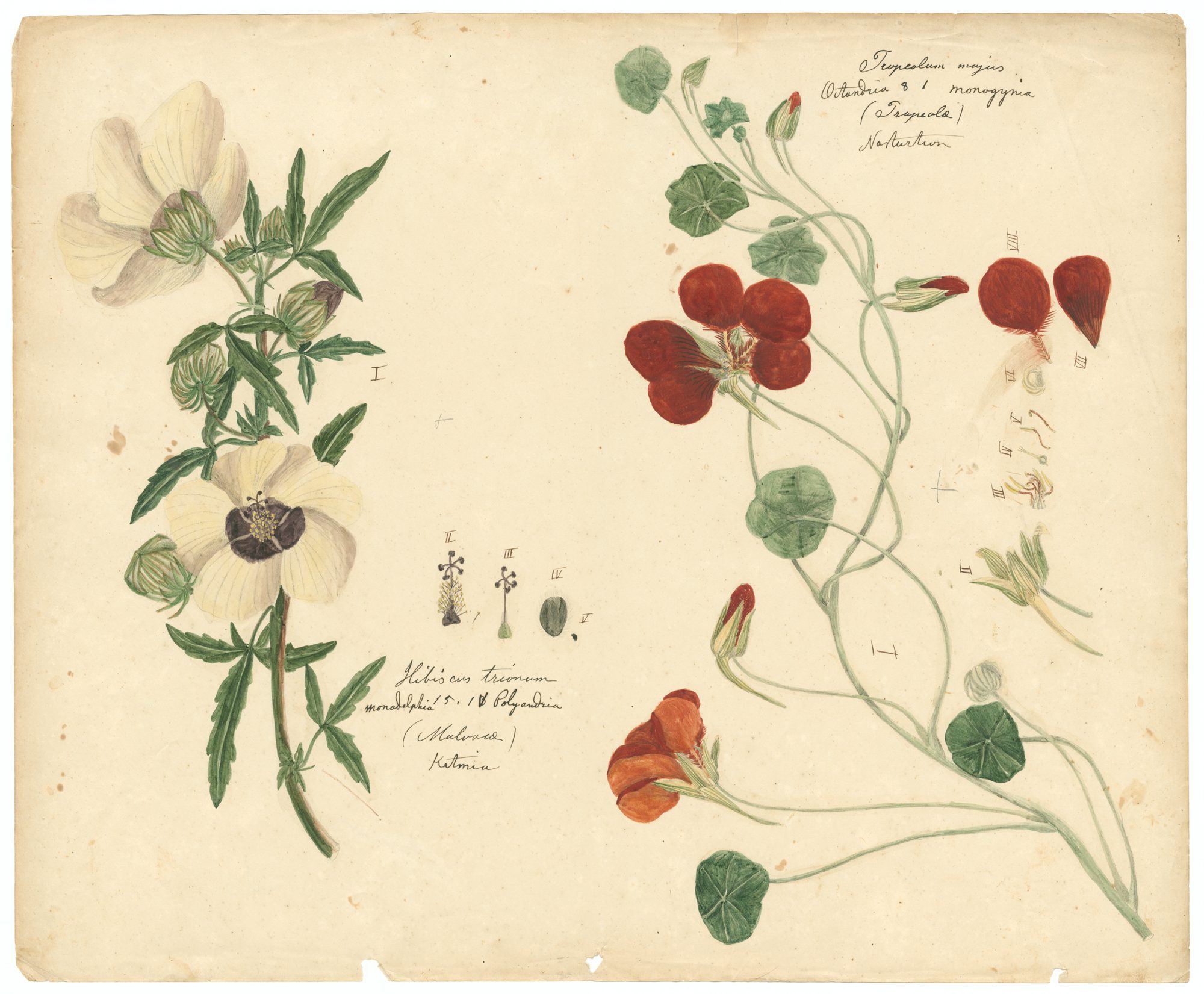

The sisters not only enjoyed field botany, they painted botanical illustrations of local wildflowers. They used “a very old edition of Nuttall’s Catalogue and Mrs. Lincoln’s abridged botany for schools” to identify their objects. Lacking the precision and quality of the finest plant illustrations, the Kron watercolors possess a simple, charming beauty nonetheless. One hundred and twenty-four of the illustrations, mostly of native species, survive in the Southern Historical Collection of UNC Chapel Hill.

While Adelaide and Elizabeth studied plants in the Uwharries, other N.C. botanists worked to identify the state’s flora. The Rev. Moses Ashley Curtis, an Episcopal rector who lived and served churches in Wilmington, Lincolnton, and Hillsborough, was the leader. He studied the previous research of earlier plant experts in North Carolina, collaborated with leading international experts, and developed a network of scientific associates across the state. His career as a North Carolina botanist culminated with the publication of A Catalogue of the Plants of the State, With Descriptions and History of Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines (1860) and A Catalogue of the Indigenous and Naturalized Plants of the State (1867).

Early botanists were not conservationists. In their era, habitat destruction and species extinction were not yet perceived to be problems. Their work, though, is related in important ways to the later conservation and ecological restoration movements. The Krons, Curtis and their allies valued nature, studied it and documented the geographical distribution of native plants. Future restorations of flora to former range will rely on the early botanists’ records to identify where native plants originally grew.

The beauty of the Kron illustrations remains an inspiration and invitation to escape to the woods. When modern nature lovers enjoy the thrill of finding and identifying a rare wildflower in the Uwharries, they are walking in the footsteps of Adelaide and Elizabeth Kron.

A Stanly County Museum exhibit on the Kron family , originally set to close Dec. 18, will be open until March 18. The museum is at 245 E. Main St. in downtown Albemarle, about 45 miles east of Charlotte. Hours: Wednesday through Friday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. The Kron House historic site in Morrow Mountain State Park is open seven days a week.

Richard Rankin is an educator, historian, conservationist and native of Gaston County. He was assistant professor of history and vice president for institutional advancement at Queens University of Charlotte for 13 years. Since 2001 he has been headmaster at Gaston Day School.