What birds tell us about Mecklenburg’s environment

We feed them in our backyards, thrill to their springtime calls and watch with wonder as they flock in the fall. But for scientists, the birds of the Piedmont Carolinas also serve as messengers of the health of the region and as evidence of changes in the landscape.

Now, for the first time, a mostly volunteer team led by biologist Don Seriff, natural resources coordinator-supervisor with Mecklenburg County Natural Resources, is compiling a record of every bird species that ever called the county home – and documenting those that still live here today.

The project, sponsored by the Mecklenburg Audubon Society, has relied heavily on “citizen scientists” to scour the streets, woods and backyards of the county for a five-year period and document the birds they found. Bird atlases have been created at the state or national level, but it’s rare for a county to pull off such a sprawling and time-intensive project. The book, which will be packed with photos and original illustrations, is slated for a 2016 publishing date. Seriff spoke about what the work has already revealed.

Q: What have you learned about the birds the county used to have 100 years ago or more?

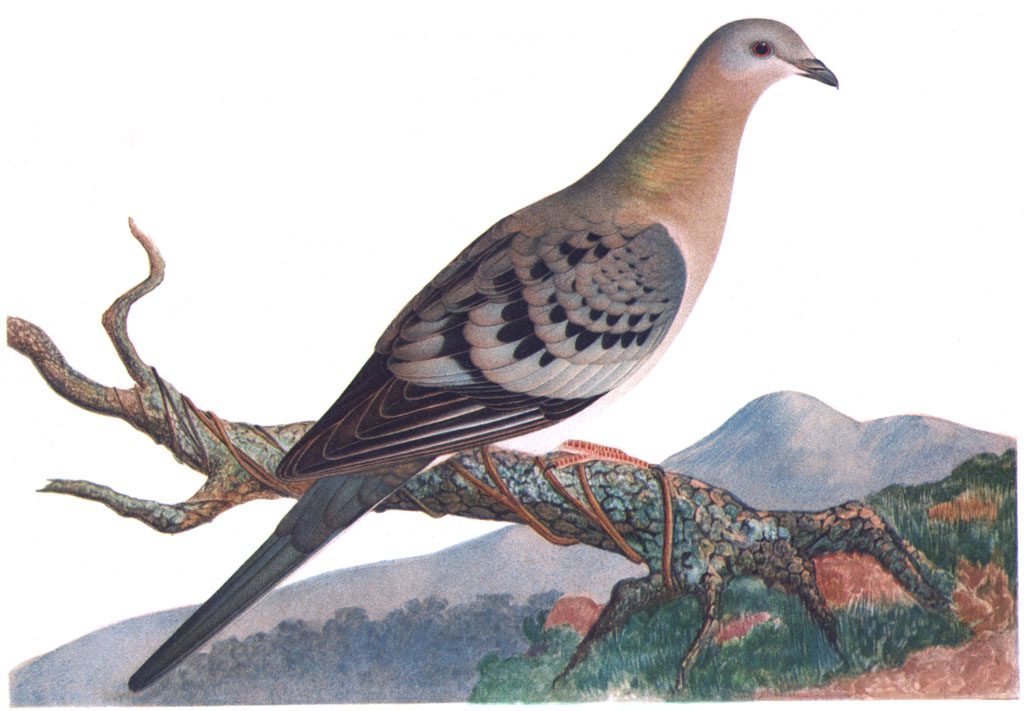

A: We have confirmed (historical) records of 309 species of birds observed in Mecklenburg County. This number includes two extinct species – the Carolina parakeet and the passenger pigeon – and two others that have not been seen here in the past 50 years, the king rail and Bewick’s wren. (We) confirmed 102 of these species as breeding in Mecklenburg County today.

Big Biird

Q: How did you dig up information on species that have vanished from our area?

A: We conducted a very thorough review of the published ornithological literature. We scoured the archives of several state and national museum collections and government agency archives. We reviewed data from more than 80 museum and university bird collections and egg collections, as well as hundreds of pages of field notes of experienced birders. We also compiled the results of all known ornithological research conducted in this area. The end result is a database of almost 200,000 bird records and an archive of thousands of historical accounts, unpublished field notes, survey results, etc.

Q: What does that research tell you about the health of the county’s bird life?

A: The rapid rate of development in our county has resulted in the decline of certain bird guilds [groups of species in a community that exploit the same set resources but are not necessarily closely related taxonomically], especially grassland and shrub land birds and birds dependent on large patches of forest.

In 2007, Mecklenburg County’s Conservation Science Office presented a “State of the Birds” report to the Mecklenburg County Board of County Commissioners that provided an initial baseline assessment of the status of our breeding bird species. The 2007 results indicated that 31 percent of our local breeding bird species were designated secure, 42 percent were designated vulnerable, 17 percent were deemed imperiled and 7 percent were believed to be critically imperiled as local breeding birds. Three percent were already extinct from the county.

A detailed report will be prepared in 2017 that will compare and contrast changes in our bird community over the past decade.

Q: What were a few of your more surprising findings?

A: Seven species that once bred here no longer do so. Many other species are restricted now to small habitat patches scattered about the county. The loggerhead shrike could be the poster child for our declining grassland and shrub land birds. Shrikes once commonly bred throughout our region. The recent breeding bird atlas effort failed to find a single breeding pair. The last known nesting pair were trying to survive in fields along the edge of the Regal Starlight movie theater parking lot near UNC Charlotte. They disappeared.

[highlight] “We are losing the birds that rely on the highest quality natural areas and replacing them with increased populations of species that can pretty much adapt to making a living anywhere.” — Don Seriff, natural resources coordinator, Mecklenburg County [/highlight]

We discovered three species, the Mississippi kite, bald eagle and common raven, which represent species that are expanding or recolonizing former breeding habitat. And the pair of peregrine falcons discovered nesting in downtown Charlotte can be considered the result of a successful conservation initiative by dedicated biologists to re-establish an eastern breeding population after extirpation from the impacts of DDT and other environmental contaminants.

Q: Are there large, overall shifts in the types of species that make their home in in the region?

A: The trend is away from habitat specialists to habitat generalists. We are losing the birds that rely on the highest quality natural areas and replacing them with increased populations of species that can pretty much adapt to making a living anywhere.

Q: In what way does the story of the region’s birds tell the story of the region’s health?

A: In the past two decades, Charlotte’s rapid rate of development and the increasing impact of changing environmental conditions have resulted in the loss or decline of bird species here. If we work hard and plan well, we can stop the loss and reduce these declines to keep Mecklenburg County, the core of the greater Charlotte region, a healthy environment in which all our native species can thrive.

Q: This area is rich in its birding past, as you’ve discovered. How did Charlotte’s robust group of “early birders” contribute to the body of knowledge about American bird life?

A: Organized bird clubs have been active in Charlotte for over a century. I have compiled local bird articles from 1845 onward. I have archived original field notes of Charlotte birders from 1926 onward. Together, with collection data and published ornithological records, these sources provide an ongoing picture of bird life here for the past 150 years. I always encourage birders to record their information and share it. Alone, the data might not seem important but, when combined over time, it becomes a very valuable treasure for future biologists.

Q: What fascinates you about birds?

A: I have loved exploring nature and watching all varieties of wildlife since I was a kid growing up in the fields and woods of east Charlotte. (Yes, there were fields and woods here then.)

My grandmother watched birds and maintained bird feeders. When I was little, we would sit in a special windowed alcove of the house my grandfather built for her, and we would watch the birds at her feeders with our eyes or we would grab the binoculars to get a look at the ones moving about in the trees. She would record what she was seeing on a clipboard and show us their pictures in her field guide. I guess these brief moments had a long-lasting influence on me.

I think birds fascinate everyone. They are dynamic. You can watch birds anywhere, anytime and still regularly see things you’ve never seen before.