No flood in your city? Lessons from New Orleans still apply

When New Orleans flooded 10 years ago last month, it looked to many people in America as though the city could never recover.

Today, when the word “resilience” dots virtually every scrap of writing on urban policy around the globe, New Orleans provides iconographic proof that a city is, in fact, a hard thing to kill—resilient in the face of stunning disaster.

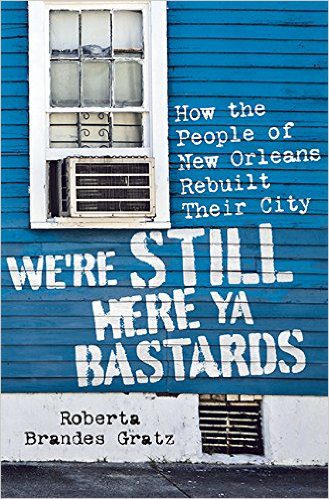

Roberta Brandes Gratz, in her newest book, We’re Still Here Ya Bastards: How the People of New Orleans Rebuilt Their City, burrows deep into reasons the city has survived and rebuilt.

The city not only had to survive Hurricane Katrina’s winds and the subsequent flooding from its flawed levees, but then it had to survive the rebuilding, as various plans from architects, planners, developers, government contractors and politicians did not always have the city’s best interests at heart. In the end, she writes, it was—and is—the people of New Orleans who are reviving the city, block by block, building by building.

Most cities in America won’t experience the horrific flooding that followed Hurricane Katrina, a storm that killed anywhere from 1,000 to 1,400 people. (So-called “official” death tallies vary.) As Gratz and others point out repeatedly, the flooding was not a “natural disaster” but caused by shoddy levee engineering and construction.

But many cities will at some point face disasters: fires, tornados, hurricanes, earthquakes, mudslides, nuclear reactor meltdowns, all the things that fuel disaster movies and nightmares.

The underlying message Gratz offers is that it’s people— the grass roots activists, determined homeowners and local business, local community groups—who will bring the city back. Yes, assistance from outside matters, and yes, rebuilding will be incremental and slow. And that’s OK. When it comes to cities, Gratz said in an Aug. 30 NPR interview, “Anything done quickly, in the end, doesn’t work.”

That’s a theme she has been exploring for most of her writing career, starting with The Living City: How America’s Cities Are Being Revitalized by Thinking Small in a Big Way in 1989, and has pursued in later books, most recently in 2010 in The Battle for Gotham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs. (Disclosure: Gratz and I serve together on the board of the nonprofit Center for the Living City and I consider her a friend and mentor.)

We’re Still Here Ya Bastards offers plenty of examples of the many people from many different backgrounds who pitched in to rebuild and to fight for their neighborhoods and their city. They range from the late Pam Dashiel, who lived in the devastated Lower Ninth Ward and cofounded the Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development, to Ann MacDonald Milling, a “classic uptown women of high social standing,” who had an idea that became Women of the Storm—a phalanx of 150 women who went to Washington in 2006 to demand congressional attention.

That women played a leading role is no surprise, Gratz writes. “Women have been at the forefront of the battle for the regeneration of American cities for over a century.” Look at a revived city and the history of the turnaround, and “you will likely find a major initiative started by a woman.” (One important Charlotte example is the role the Junior League played in kick-starting the revival of uptown’s Fourth Ward neighborhood in the 1970s.)

The book is not all kumbaya about the miracles of community workers. Nor does Gratz declare that New Orleans is healed. Many of its deeply structural problems – the “hurricane before the hurricane” as Michael Mehaffy of the Sustasis Foundation writes—remain: entrenched racial segregation and economic injustice, a flawed criminal justice system, environmental errors, and educational troubles that charter schools may or may not be successfully addressing.

Gratz details, in some cases with barely restrained outrage, numerous instances of government blundering and/or plundering. She shows how federal-government-by-private-contractor helped cheat the city and state out of public recovery funds. She devotes several chapters to the greed-enabled ineptitude of various recovery schemes.

“Public Housing and Disaster Capitalism,” explores the city’s willing demolition of its solidly built, minimally damaged public housing projects “with Georgian brickwork and lacy ironwork porches.” Instead of repairs for less cost, most of the buildings were demolished for new, mixed-income housing that, critics say, leave low-income residents with even fewer housing options.

“The Demise of Charity Hospital” describes how Louisiana State University not only got its way in closing the second-oldest continually operating public hospital in the country, a critical center of medical care, but in the process destroyed an integrated, working class neighborhood nearby. She interviews Army Staff Sgt. John Johnson, who with no official support or budget, worked around the clock along with 200 volunteers in 2005 and restored power to Charity within two weeks of Katrina. Yet now-Gov. Bobby Jindal had, as head of the state health department, in 1999 given management of Charity to LSU, which wanted a new hospital. Despite Charity’s readiness to re-open, LSU shuttered it. Gratz characterizes the whole episode as an “antidemocratic insult.”

But what does all of that have to do with any other city that might face catastrophe—or even a city not facing a catastrophe? Gratz’ lessons are clear:

- Neighborhoods matter, and the people in them matter. Paying attention to this before a disaster will make any recovery stronger.

- Large-scale projects— whether convention centers, vast new hospital complexes or tourism-focused schemes—do not create the lasting urban revival that comes with a slower, block by block process that protects small, local businesses.

- Big plans can create big mistakes, a lesson seemingly obvious to anyone after the failures of federal Urban Renewal across the country, yet a lesson still often ignored.

As New Orleans radio host Gwen Thompkins said, in an NPR piece aired Aug. 29, “Real recovery happens where most people don’t notice—on a lunch date, singing along to a headliner in a club, working 12 days in a row to make sure somebody’s house gets fixed the right way.”

That’s true for all cities and towns, even those not stumbling their way toward recovery from a disastrous flood. It’s people’s lives that create the city—its history, its present and its future—and in the end they are who will make the difference.

Mary Newsom is associate director of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute. Opinions here are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.