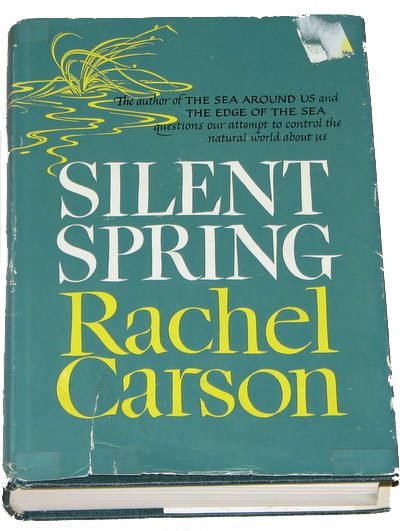

Remembering Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’

By the mid-1960s, the U.S. had become sensitized to the environmental damage caused by harmful human practices, particularly the use of pesticides and DDT, following Rachel Carson’s 1962 pivotal book on this issue, Silent Spring. Carson was an eminent biologist, ecologist, and writer at a time when women in the fields of science and research were rare. Last Thursday, Sept. 27, marked the 50th anniversary of its publication, widely recognized as the beginning of the modern environmental movement. This golden anniversary is a good time to reflect, again, on a remarkable individual.

Rachel Carson was born into a poor family in 1907 on a farm in Springdale, Pa. Her love of animals and nature came early, and at 10 she published her first story about nature in a children’s magazine. She went to college on scholarships, first at Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University), earning a degree in biology, and later a master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University. Early in her career, she was an aquatic biologist and editor-in-chief for what would become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. While there, she published a series of articles on Atlantic Coast wildlife refuges, numerous pamphlets and bulletins about conservation and her first two books, Under the Sea-Wind and the best-seller The Sea Around Us.

Silent Spring’s title comes from Carson’s evocative image of a spring that would come without the song of the robin, mornings breaking in eerie silence. In it, she decried the indiscriminate use of pesticides and their harmful effects on the environment. Predictably, the pesticide industry attacked her vehemently and attempted to discredit her as she spoke out about her findings. She was branded a “hysterical woman” and investigated by the FBI, and the chemical industry called her research unscientific. Undaunted, she resisted pressure from industry and government to abandon her research and persevered in her mission to educate the public. Carson biographer Linda Lear, in a Sept. 27 interview with Wendy Koch of USA Today, sheds light on the passion expressed in Silent Spring. About halfway through its writing, Carson learned that her breast cancer had metastasized. “Then everything changed in her life,” says Lear. “Her language got more apocalyptic. She realized she might not live to write another book … so she better say all she had to say in this one.” She died at age 57, just 18 months after the book’s publication.

Silent Spring’s title comes from Carson’s evocative image of a spring that would come without the song of the robin, mornings breaking in eerie silence. In it, she decried the indiscriminate use of pesticides and their harmful effects on the environment. Predictably, the pesticide industry attacked her vehemently and attempted to discredit her as she spoke out about her findings. She was branded a “hysterical woman” and investigated by the FBI, and the chemical industry called her research unscientific. Undaunted, she resisted pressure from industry and government to abandon her research and persevered in her mission to educate the public. Carson biographer Linda Lear, in a Sept. 27 interview with Wendy Koch of USA Today, sheds light on the passion expressed in Silent Spring. About halfway through its writing, Carson learned that her breast cancer had metastasized. “Then everything changed in her life,” says Lear. “Her language got more apocalyptic. She realized she might not live to write another book … so she better say all she had to say in this one.” She died at age 57, just 18 months after the book’s publication.

In 1969, five years after her death, the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge in Maine was named to honor her memory and lifelong work in environmental science. Other national conservation areas bear her name, including the National Research Reserve in Beaufort, N.C. Carson clearly articulated the connection between the preservation of wild nature, human happiness and fullness of life. She issued a clarion call to value all life, both human and nonhuman, and in so doing changed a nation forever. Thank you, Rachel Carson. We’d like to tell you that the spring is still singing.

About the photo above: National wildlife artist Bob Hines (1912-1994) and USFWS agency writer and editor Rachel Carson (1907-1964) spent many hours along the Atlantic coast visiting national wildlife refuges and gathering material for many of the agency’s pamphlets and technical publications.Here, Hines and Carson search out marine specimens in the Florida Keys around 1955, which Hines drew as illustrations for Carson’s third book, “The Edge of the Sea.” By this time, Carson had left the Interior Department agency and was writing full-time as a nationally known author and popularizer of biological subjects. Image: USFWS/Rex Gary Schmidt.

Melissa Currie is a doctoral student in the Department of Geography & Earth Sciences at UNC Charlotte. Views expressed here are hers and not necessarily the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.