Revolutionary thinking for Red Line rail

MOORESVILLE – “Revolutionary” is not too strong a word for plans laid out Tuesday to a room full of government officials, consultants and interested laypeople.

At a public workshop in Mooresville, some 150 people heard a lengthy and detailed proposal for reviving a planned but still unbuilt commuter rail line to Iredell County. Simply the fact discussions are taking place is a development of some importance. But the plan’s details illustrate two big departures from business as usual in the Charlotte region.

| Click here to download the full Red Line presentation made Dec. 13 in Mooresville. |

First, the plan involves legally binding regional cooperation.

Second, the current crunch on public money is forcing some long-needed new thinking about innovative financing for transportation.

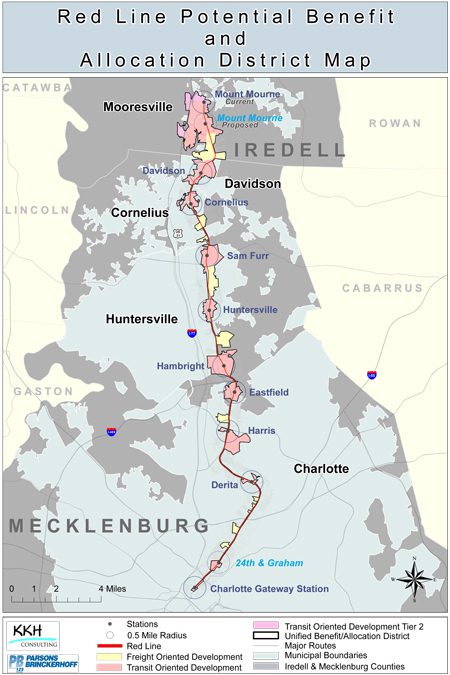

Even for a region with plenty of regional “discussions” for decades, what’s being proposed is a major leap forward for working across county boundaries. The complicated proposal depends, in part, on seven local governments agreeing to form a new legal entity called a Joint Powers Authority. Members would be Mecklenburg and Iredell counties, and Charlotte, Huntersville, Cornelius, Davidson and Mooresville, plus the N.C. Department of Transportation and the Charlotte Area Transit System. The authority wouldn’t have taxing authority.

Not since the great Mecklenburg annexation/spheres-of-influence agreements of the 1980s and the formation of the Mecklenburg-only Metropolitan Transit Commission in the 1990s have so many local governments been asked to come to a formal, legal agreement of similar importance. And this time, the agreement must cross county lines. That’s a rare proposition around here, where even next-door counties can be places with entirely different political cultures. In addition, most of the counties outside Mecklenburg harbor, if not fear, then at least wariness of Charlotte’s behemoth footprint.

Not since the great Mecklenburg annexation/spheres-of-influence agreements of the 1980s and the formation of the Mecklenburg-only Metropolitan Transit Commission in the 1990s have so many local governments been asked to come to a formal, legal agreement of similar importance. And this time, the agreement must cross county lines. That’s a rare proposition around here, where even next-door counties can be places with entirely different political cultures. In addition, most of the counties outside Mecklenburg harbor, if not fear, then at least wariness of Charlotte’s behemoth footprint.

But if there’s to be any hope of prudently guiding this huge and sprawling metro region away from financially unsupportable growth, it will have to come with a large dose of inter-county cooperation. After all, the choice at hand is this: Cooperate, and continue to progress, or maintain geographic silos and see this region bypassed by other, more cooperative metro regions.

Viewed that way, what happens to the Red Line proposal could well be a harbinger of the region’s future.

The other reason Tuesday’s summit and the Red Line plan carry major significance is this: For the first time since the 1998 transit sales tax campaign, the Metropolitan Transit Commission and its member governments are putting on their thinking caps about financing.

Until now, most people around here pretty much assumed transportation money – including for roads, not just transit – would flow down like water from the feds and the state. And for transit, you’d also get money from the half-cent sales tax, collected only in Mecklenburg. (Individual cities, of course, also use local tax money for local street projects that aren’t part of the vast state road network.)

Even before the 2008 financial crash, it was starting to look as if the MTC couldn’t build out its five-corridor plan in 25 years without more money than it could expect from the half-cent sales tax and those expected state and federal funds. Since then, the recession and continuing high unemployment have battered the sales tax revenues. Another difficulty specific to the Red Line has been that it doesn’t meet today’s eligibility standards for federal transit money; almost no commuter rail projects do because of the way the feds calculate ridership projections. Until a year ago, the transit commission appeared to believe it had few options beyond delaying transit construction for decades, pushing for a politically unlikely sales tax increase or passively hoping sales taxes revive.

Finally, with help from the N.C. Department of Transportation and some savvy consultants, it has decided to get more creative about finding money. The MTC’s Red Line Task Force and NCDOT have looked around the country at how other metro areas are building transit systems. Two important words arose: value capture.

That means recognizing that building public infrastructure such as highways and transit lines makes nearby property more valuable. (Ever notice how land speculators like to buy property 20 years before the state highway goes through?) Instead of letting public spending enrich private landowners with little monetary benefit to the public, why not “capture” some of that increased value for public purposes?

A value-capture proposal would use some of the new, higher tax revenues from the now-more-valuable property to pay off bonds that would be sold to pay for building those same infrastructure improvements. The Washington Metro, the Dallas Area Rapid Transit system and the Portland, Ore., streetcar system have all used value capture in their construction.

The Red Line plan proposes two value-capture techniques. One is tax-increment financing (TIF) – using some of the expected higher property taxes to pay off bonds. Another is a special assessment district, formed when a majority of the income-producing property owners (i.e. not owner-occupied residential homes) along the Red Line rail line agree to an extra property tax (75 cents per $100 in assessed property value is what’s been proposed). Most of that tax revenue would help fund construction, but 25 percent would go to the general fund of the local governments.

The proposals laid out Tuesday must undergo weeks of examination and discussion among elected officials before any decisions. Will the cities and counties feel comfortable that, as the NCDOT and the consultants keep assuring them, they won’t be financially responsible if the bonds can’t be repaid? NCDOT officials have said the state would back the bonds, not the Joint Powers Authority.

And nothing is certain. For instance, Iredell County is a key player; yet while all other affected elected bodies had representatives in the room Tuesday, not one Iredell County commissioner was at the Mooresville meeting. What does that mean for the proposal’s chances?

Will the affected property owners from uptown Charlotte north through Mooresville agree to higher taxes? Will anti-tax elected officials refuse to let even willing property owners raise their own taxes?

Yet even if this proposal ultimately fails, it is setting important precedents. It’s recognizing that the state needs to look at more sophisticated ways to pay for the public infrastructure it builds – and that includes highways as well as transit.

And it’s recognizing that, like it or not, no metro area can accomplish what it needs to unless its member governments cooperate in more formal ways than just going to meetings and talking together.

Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and not necessarily the collective view of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute staff or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.