What impact will ‘disruptive innovations’ have on Charlotte’s transportation system?

This story is part of the Transit Time newsletter, a partnership between the Urban Institute, the Charlotte Ledger and WFAE. Find out more and subscribe here.

Charlotte plans to spend billions of dollars over the next two decades building new rail lines, a better bus system, greenways and roads. But in an age of self-driving cars, drones, hydrogen train and cheap, futuristic tunnels, is the city building tomorrow’s transportation system with yesterday’s technology?

So far, the discussion has mostly centered on how to pay for Charlotte’s transit plans (transit tax? federal grants?) and where different routes should go (directly to the airport, or a mile away on Wilkinson Boulevard?). But there are other discussions swirling around on the sidelines, ideas about more futuristic modes of transportation and whether these could upend transit and transportation as we know them.

“I think we need to have a real analysis of the disruptive innovations that are coming in transportation. I’ve mentioned it every time we’ve brought this up for the last three years. And it’s about autonomous vehicles. It’s about all of these things,” City Council member Tariq Bokhari said at a December meeting.

The Charlotte Moves report driving the city’s recommendations doesn’t mention emerging technologies, and there’s been no formal discussion about including them in the presentations from consultants thus far. And yet they keep cropping up, in council meetings, local media and conversations around the region.

Prognostication is a dangerous game. Get too enthusiastic, and you risk looking naive as a monorail-promoting shill on “The Simpsons.” Too pessimistic, and you might wind up a cautionary tale like the semi-mythical “Great horse manure crisis of 1894,” when futurists of the day predicted that more people and businesses using more horses meant city streets would inevitably end up buried in poop. They didn’t foresee the automobile.

Despite these risks, Transit Time decided to look at four potential disruptive technologies — autonomous vehicles, tunnels from Elon Musk’s Boring Co., hydrogen-powered rail and truly far-out stuff like flying cars — to see what might actually come to pass, what the obstacles are, and whether they might actually solve our transportation woes:

Self-driving cars: Almost there technologically, but more traffic?

The idea: Cars that can drive themselves are tantalizingly close to becoming a widespread reality. They’re already being road-tested from San Francisco to Moscow. Waymo, Google’s self-driving car division, has covered 20 million miles on public roads since 2009.

The technology isn’t perfect — a Tempe, Ariz., woman died in 2018 when an autonomous vehicle with a backup driver ran her over crossing a street — but it’s come a long way in the last decade.

The benefits to widespread autonomous vehicles could be substantial. Most new apartment buildings and office towers, even in the densest, most urban parts of Charlotte, still come with huge parking decks that eat up valuable land and rob blocks of street-level vitality. Self-driving cars could, in theory, drop you off and park themselves at a central location, leaving developers more room to build and freeing us from the constraints of massive parking decks.

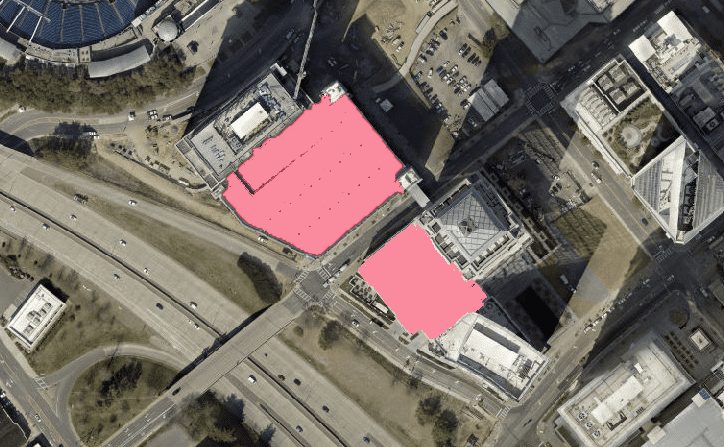

Legacy Union, a 10-acre development in uptown Charlotte. Like most Charlotte developments, it features huge parking decks that occupy much of the developable land, despite being near a transit stop.

Legacy Union, a 10-acre development in uptown Charlotte. Like most Charlotte developments, it features huge parking decks that occupy much of the developable land, despite being near a transit stop.

Advocates also say self-driving cars will be able to drive closer together and with far fewer accidents, without mistake-prone human drivers behind the wheel. That could improve safety and cut down traffic congestion. Throw in widespread adoption of electric vehicles to reduce carbon emissions, and we could have ourselves a climate-friendly, hassle-free solution to congestion, without spending on public transit, right?

The downside: As Shannon Binns, executive director of Sustain Charlotte, points out, self-driving cars still take up the same amount of space as regular cars. And in a region where half of workers commute in from outside Mecklenburg County and the vast majority drive alone, self-driving cars still mean a lot of cars on the road. Throw in a few hundred thousand additional residents expected over the next couple of decades, and you still have a formula for growing congestion.

“The geometric fact that we talk about in transportation planning is that 40 people in cars take up more space than 40 people in transit,” Binns said. Binns is skeptical that autonomous vehicles will shave off enough travel time to counter the traffic impacts of several hundred thousand more vehicles on our roads in the next 20 years.

“As more and more people move to our region, the demand for that limited space is only going to grow, and we have to use it as efficiently as we can,” said Binns, an advocate for building more transit.

There’s also some evidence that we might use our cars even more if we don’t have to drive them. A study published in 2018 and led by Berkeley-based transportation researchers tried to simulate giving people self-driving cars by providing a fully chauffeured, free vehicle (the closest equivalent to a fully autonomous vehicle they could get). They found that people substantially increased their vehicle miles traveled and were more likely to send their cars empty on “ghost” runs to pick things up for them.

So, if we all have autonomous vehicles some day, we might be likely to drive them more and send them on more trips we’d otherwise have skipped or consolidated, leading to more cars on our finite streets.

Elon Musk’s tunnels: Lots of interest, but still unproven

The idea: Ever since Elon Musk announced his intention to make tunneling cheap, easy and fast, there’s been a lot of excitement among municipal officials across the U.S. Instead of paying prices like $3.2 billion for a 2.6-mile subway extension (like Los Angeles’ Purple Line), Musk’s Boring Co. touted new technologies that would bring the cost of his transportation tunnels closer to $10 million a mile.

Elon Musk’s Boring Co. offers the promise of inexpensive tunnels beneath congested cities. (Source: The Boring Co.)

The first “loop” system opened in Las Vegas this year, ferrying visitors around a single tunnel in a fleet of human-driven Teslas. Officials in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., are hiring the Boring Co. to drill a new tunnel to the beach. And mayors in Mecklenburg’s northern towns are excited about the prospect of maybe finding a way to bring rapid transit to Davidson, Cornelius and Huntersville without getting Norfolk Southern’s permission to use freight tracks for the Red Line.

“For me, it’s as simple as 21st-century technology vs. 100-year-ago technology,” Davidson Mayor Rusty Knox told Transit Time in an interview. Knox and his fellow mayors talked about the possibility of using a tunnel to span much of the 20-plus-mile distance between their towns and central Charlotte on “Charlotte Talks” several weeks ago.

“The Red Line discussion is dead in the water,” he said. “This is the only option.”

Knox said he’s heard several presentations from Boring Co. representatives and participated in meetings with other local mayors and town managers about the possibilities. Bokhari, the City Council member, has also raised the possibility of hiring the Boring Co. to tunnel under crowded intersections.

The downside: Still, skeptics have pointed out that most of the Boring Co.’s announced projects haven’t come to pass. High-profile tunnels for Chicago and between Washington and Baltimore have been quietly shelved. And the company’s product so far isn’t really public transit, or the high-speed, 100-mph-or-faster, high-capacity autonomous vehicles Musk originally planned to put in his new tunnels. In Las Vegas, the system runs on Teslas with human drivers, meaning that even though it’s underground, it’s basically an Uber right now.

“You’re gonna have to sell people on riding in tubes,” said Knox. Knox acknowledged the idea might seem far out, but said that watching Musk and seeing the company’s presentations left him “dazzled” — and convinced it could work. He expects the technology to catch up and advance beyond the modest Vegas pilot.

“I equated it to 100 years ago sitting in the audience with Albert Einstein,” Knox said of watching online talks from Musk. “I don’t want to see it (tunneling) discounted just because it’s not the platform we’re using now.”

Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles acknowledged the discussions with Boring Co. representatives. But she said (also on “Charlotte Talks”) that it seems like the Boring Co. is more interested in doing a short pilot tunnel.

“The Boring Co. is really interested in more of a short distance,” she said. “They were actually asking if we would be willing to participate in an experiment at the airport instead of a long commuter rail line. Now we’ve turned it over to our engineers.”

Hydrail: cleaner than diesel, but a long way to go

The idea: Diesel trains produce pollution, and electrified train routes are expensive to build. A former north Mecklenburg legislator touted an alternative recently to a diesel commuter rail (which he called a “horse and carriage line to Charlotte”) in The Charlotte Observer: A hydrogen-powered train.

Hydrail, as it’s known, is a technology that uses hydrogen fuel cells to generate electricity on board trains and power them without emissions and without electrified tracks or overhead wires. And one of the biggest hydrail advocates in the world is from Mooresville: retired AT&T executive Stan Thompson.

“The paradigm has shifted globally,” said Thompson. “Diesel is going away. Electric is too expensive. … 2035 is emerging as kind of an annus mirabilis for the end of diesel.”

Thompson has organized hydrail conferences, including at UNC Charlotte, and been a tireless champion of the technology for nearly two decades. There are growing signs that hydrail could catch on, like a pilot project in San Bernardino, Calif., the first passenger hydrail service in the U.S., and Germany’s use of hydrail on a 62-mile passenger line.

The downside: But — especially as automakers have shifted to electrics and away from hydrogen fuel cells — the promise of a hydrogen-powered economy remains elusive. There are an estimated 40,000 diesel locomotives in the U.S., and replacing them all won’t be fast. San Bernardino’s train is expected to start operating in 2024.

Flying cars: Fun to imagine, but probably still years away

The idea: When it comes to the future, “flying cars” are the promised technology we never seem to get. That could change someday — as the New York Times noted in June, there’s serious investor interest and startups trying to make “Uber meets Tesla in the Air” a reality. Morgan Stanley forecasts that flying cars could become common by 2040 because of “accelerating tech advances and investment.”

Closer to home, Bokhari, council’s resident futurist, mused during the city’s 2040 plan debates about Amazon bringing a “floating refrigerated warehouse” that serves groceries via drone one day. Amazon received a patent in 2018 for “product-distribution warehouses that float in the sky, and are carried and held aloft by blimps.”

Will such innovations obviate the need to drive to the supermarket, and wipe out food deserts? Will air taxis float us all — at least the lucky ones — over backed-up I-77 and straight to our offices?

Flying transportation is definitely the trickiest to forecast. On the one hand, drone delivery is a reality, at least in pilots and PR stunts like Domino’s pizza deliveries via drone a few years back. On the other hand, would you really take a flying car with no pilot?

The downside: One thing’s certain: If flying transportation and floating refrigerated warehouses really do materialize, they’ll face the same thicket of local regulations other new transportation options have. Remember the controversy and local regulatory hurdles e-scooter companies jumped through a few years back? Multiply that by the Federal Aviation Administration, add in that Charlotte has one of the world’s busiest airports about eight miles from its downtown, and it’s tough to see a world where we’re all zipping above traffic and watching our groceries float down from a sky warehouse.

Of course, we could eat those words in 50 years, just like the horse manure catastrophizers look pretty silly with the benefit of hindsight. Only one thing’s certain about the future and how we get around: Change will come, and we probably won’t get all our predictions right.