Mapping Charlotte’s lost buildings: Demolitions on the rise again

By Nathan Griffin

Charlotte’s aging buildings are being torn down at an alarming rate, the product of a fast-growing population and strong real estate market.

Some were fine examples of classic architecture, like the long since demolished Masonic Temple on South Tryon, an Egyptian Revival-style building from 1914, or Mecklenburg County’s first main library, built in 1903 with a grant from Andrew Carnegie.

Others were notable for their cultural and historical connection — for instance, the recently demolished library and auditorium at Central Piedmont Community College’s central campus, which provided a community resource for learning and gathering. When these buildings are destroyed, some small part of the character and history of the city is lost with them.

[Read more: Single-family housing once dominated Mecklenburg, but that’s changed]

Most of these lost buildings aren’t architectural wonders, however — they’re simply older homes in quickly gentrifying neighborhoods. But these houses make up an important part of the city’s affordable housing stock.

Given the pace of redevelopment, how can Charlotte preserve its history and provide affordable housing while still meeting the needs of a growing city?

Historic Properties

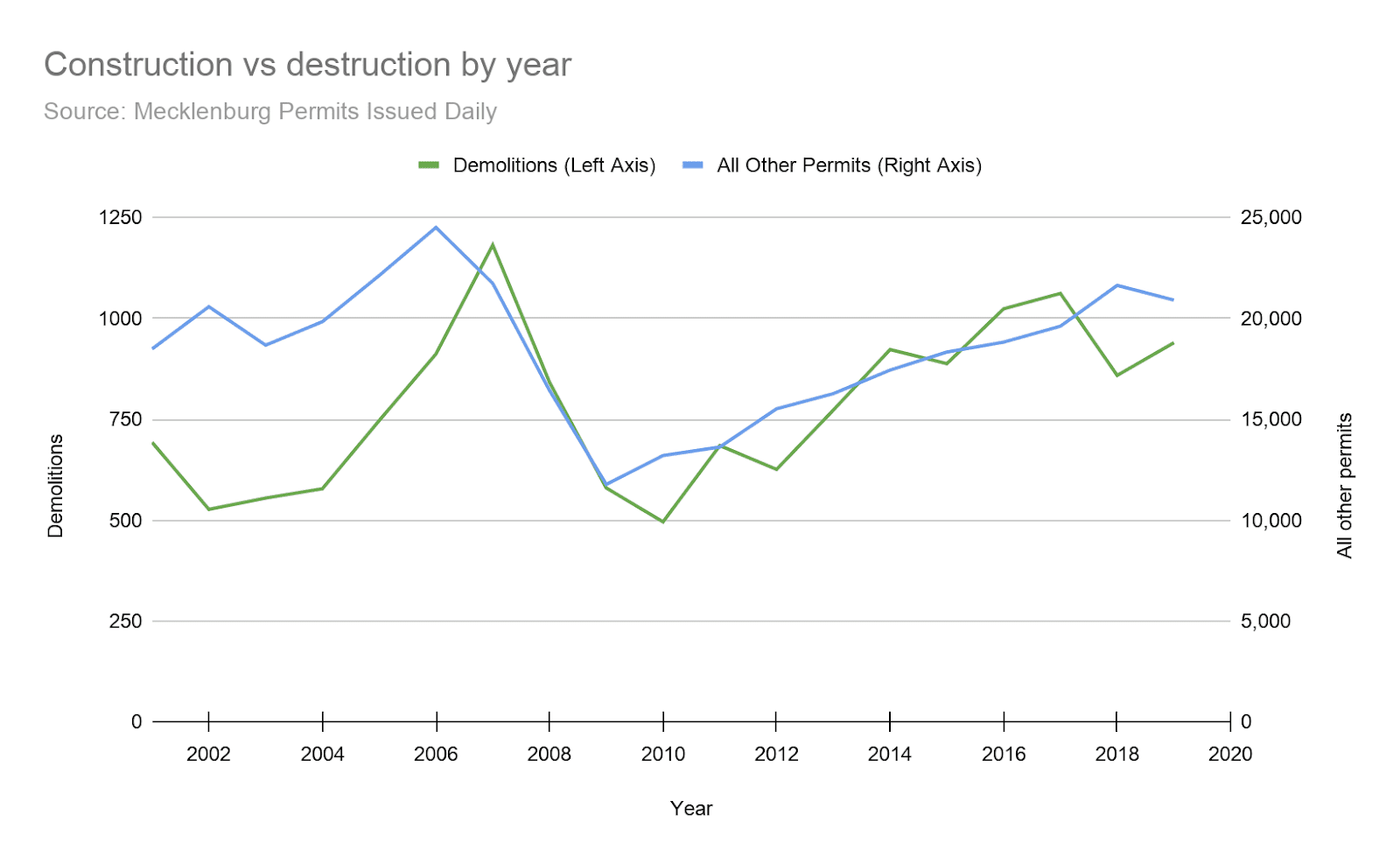

Demolition activity closely correlates with demand for new construction. Both demolition and new construction permits rose during the frenzy of development leading up to the 2008 recession. In the wake of the financial crisis, permits fell sharply, and then rebounded slowly. In 2019, over 1,000 structures were demolished — still below the 2007 peak.

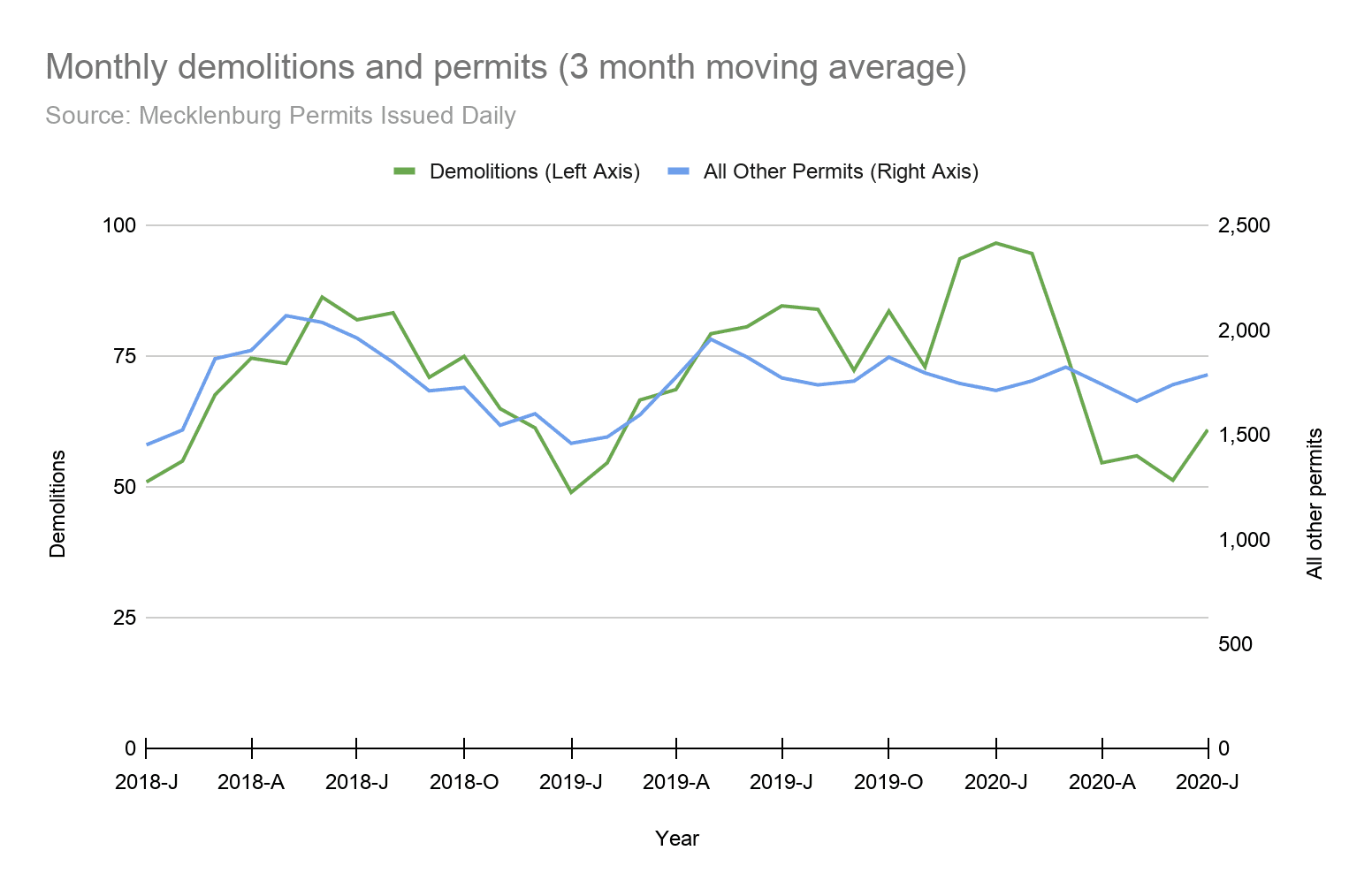

Despite the pandemic — which has caused a record contraction of economic output and the loss of tens of millions of jobs — demand for housing and new construction have remained strong. Permits for commercial and residential structures held steady through July. In June, Charlotte area home prices rose 6.8 percent and closed sales were up 2.5 percent from the previous year.

Renters, however, have been hit particularly hard, partly because they typically have less savings and are more likely to have been laid off. This is reflected in rent prices, which have fallen by 1.5 percent since March, according to Apartment List. Charlotte ranks eighth in the nation for rapidly falling rent, behind large, expensive metros like New York City and San Francisco.

Before the pandemic, demand for Class A office space grew steadily as many corporate headquarters relocated to Charlotte. Honeywell, Ally, and Corning Optical are developing high-end office space in the city. Other companies are expanding their footprint in Charlotte, such as Microsoft and Lowe’s with a new South End technology center.

Charlotte is now the 15th most populous city in the U.S., recently surpassing San Francisco. And while the need for housing and commercial space remains strong, so does the need to demolish existing buildings.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission actively seeks out properties to preserve through designation as local landmarks. They have helped to protect hundreds of properties since 1973. Included in the list are notable buildings like the Carolina Theatre, the Charlotte Coliseum, and Old St. Peter’s Hospital, among many others. But not all properties are eligible for this designation.

Dan Morrill was chairman of the commission for decades. Many of the buildings we’re losing now, such as old mill houses, don’t fit the criteria for this classification.

“It has to be something that, either because of it’s architecture or because of it’s associative history, is above the norm,” Morrill said. “The consent of the owner is not legally required, but from a political perspective, it is very important.”

Only after the approval from several agencies, including the State Department of Cultural Resources and the local governing boards, can the property be deemed a landmark.

Even then, a property can still be demolished. The commission can only delay a demolition for one year, in the hope that an alternate solution can be found during that time.

“There’s only two things that truly protect a building. One would be that whoever owns it makes their own personal decision that they’re not going to tear it down.” Morrill said. “Or, to put preservation easements on the property or to put covenants on the deed.”

He’s started a group called Preserve Mecklenburg with a goal of obtaining preservation easements on older properties. But this requires money and consent of the owner, and owners are not always willing to restrict the uses of their property.

The most successful way of preservation is often through adaptive reuse. Historic mills have staying power. Recent projects like Optimist Hall and Camp North End show that these historic structures can be adapted to become venues for dining, entertainment and office space.

Other historic landmarks can find new life too. Rural Hill Plantation in Huntersville which includes a restored 1790s era home, is now a venue for weddings and the Highland Games. Repurposing such buildings so that they can benefit the community in new ways and remain commercially viable has allowed Charlotte to hold onto a bit of its history.

Housing

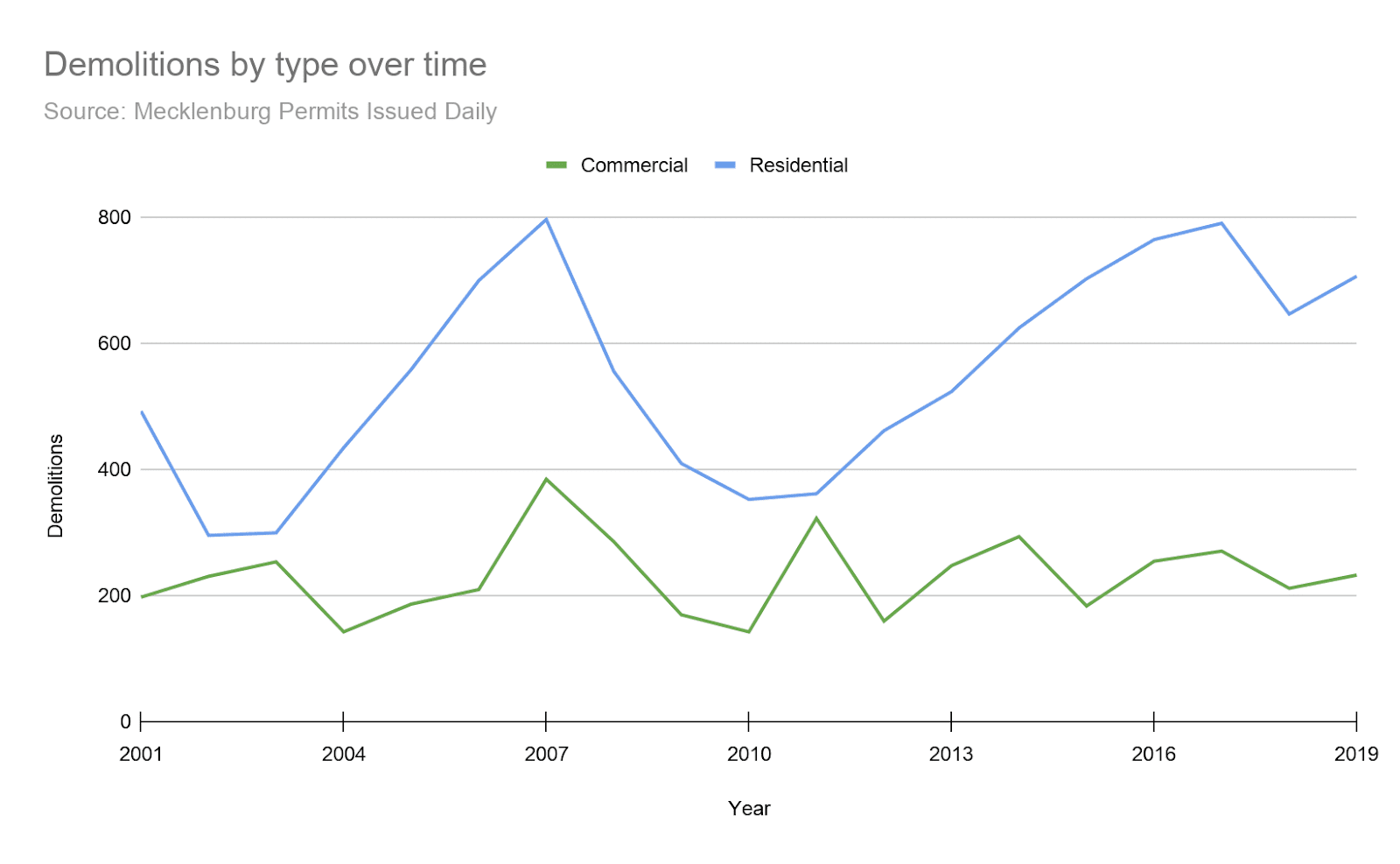

Commercial buildings often attract the most attention, but 70% of all buildings demolished in Mecklenburg are homes. Residential demolition is driven by Charlotte’s growing demand for housing. In booming, close-in neighborhoods such as NoDa or South End, high land values and demand for high-density projects are driving much of the redevelopment.

The fabric of some streets, like this one in South End, have been entirely changed. Many of the homes nearby have either been renovated or demolished to make way for new luxury housing.

What happens to properties after a home is demolished?

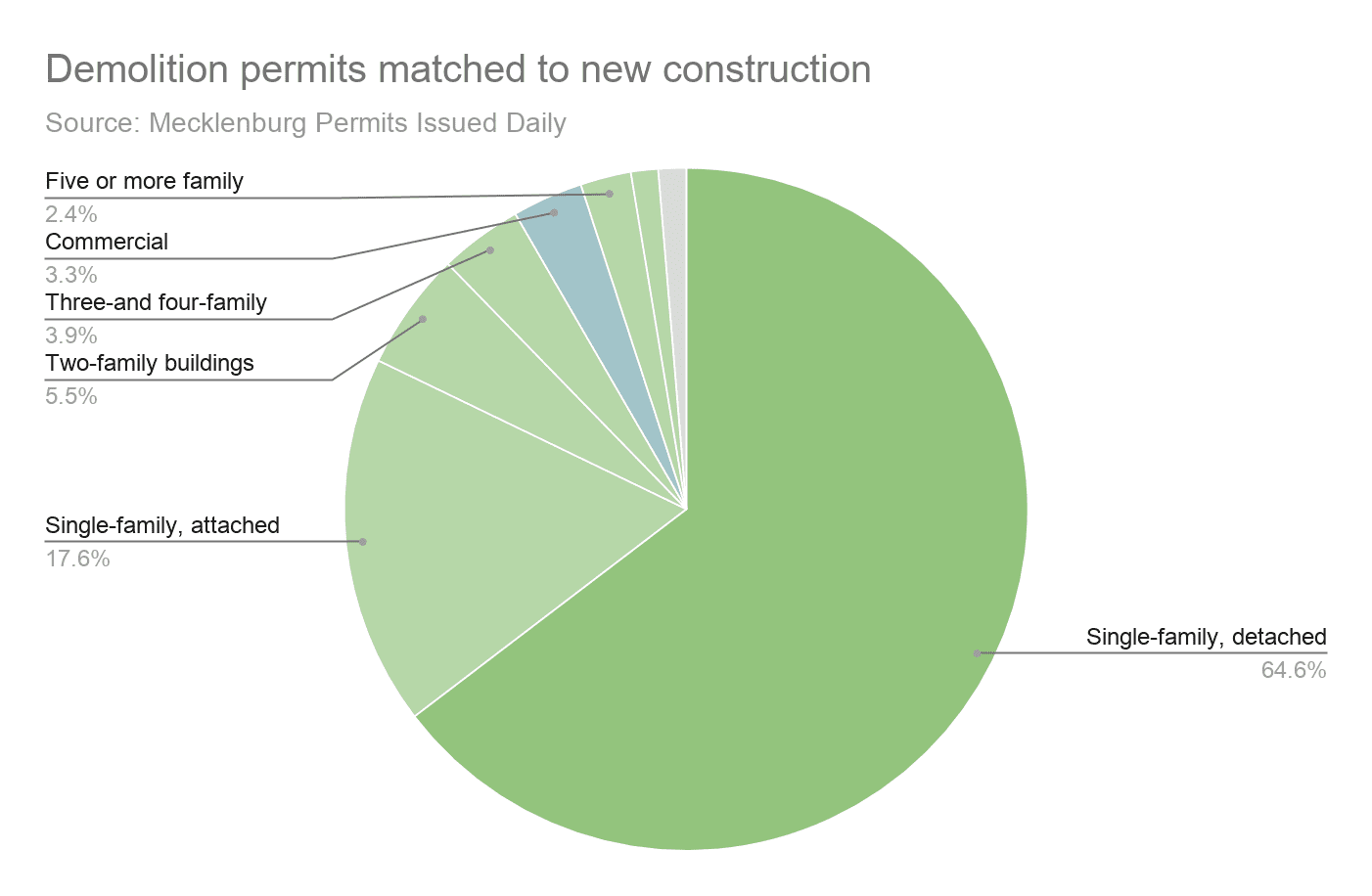

About one third of the 15,000 recorded demolitions could be matched to new construction permits at the same address: 65% of the time, single family homes are constructed on the same site, while 32% of the time, the land is used for townhomes, duplexes or other higher density residential. Only 3% of parcels are converted to commercial use. The average building cost of redevelopment is $207,000, with new houses averaging 2,650 heated square feet.

Demand for walkable, transit adjacent communities in South End has fueled new construction projects aimed at the high density apartment market. To fill this need, much of the time the only option is to tear down existing homes or businesses.

Much of the demolition is concentrated in the close-in neighborhoods like South end, NoDa, Elizabeth, Myers Park, and Wesley Heights. Gentrification is a growing concern in these areas, as housing costs rise faster than wages. Many older apartments and rental homes are torn down and replaced with new, higher end units that are no longer affordable to the existing residents unless the developer sets aside units specifically for that purpose.

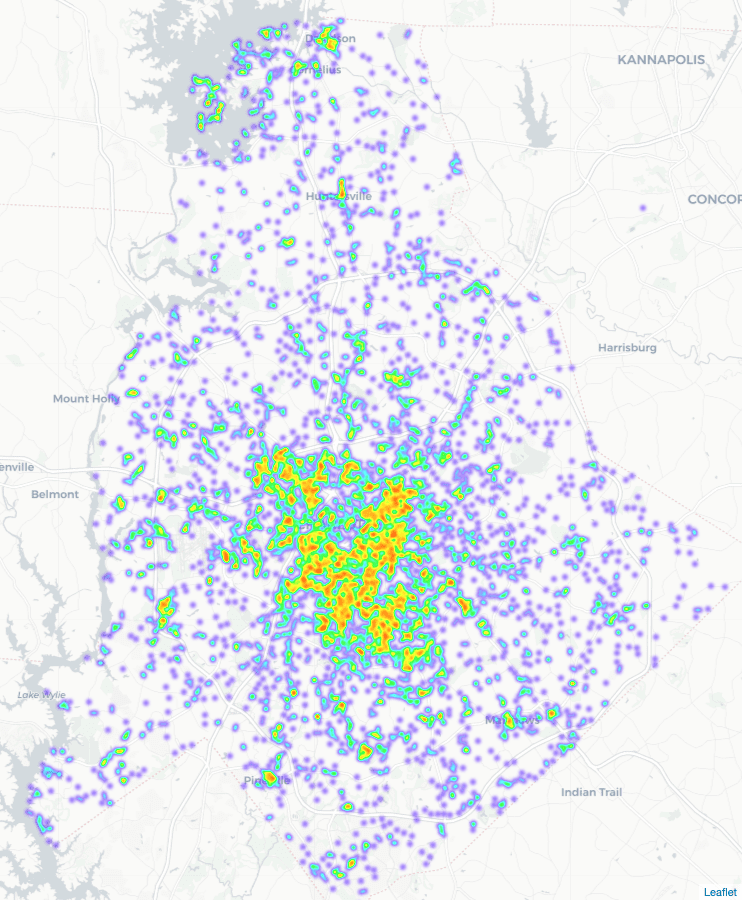

Demolition Permits since 1999, Mecklenburg County. Source: Mecklenburg Permits Issued Daily

Not surprisingly, the oldest neighborhoods are concentrated near center city. When World War II ended, congress passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, or the G.I. Bill, that provided access to low interest loans for veterans. This set off a housing boom during this period.

Much of the development was concentrated in the few “streetcar” suburbs near the city center. But Black veterans were systematically excluded from home ownership, leading to many of the patterns we still see today in segregation and disparities in homeownership rates. And many of the neighborhoods where Black Charlotteans lived are now seeing high levels of demolitions and gentrification.

After Interstate 77 was completed in the 70’s, development patterns shifted away to the outlying areas of the county, leaving many of the homes neglected and in need of major renovation or repair.

While many homes are cleared to make room for new construction, some long neglected homes were deemed unfit for habitation, and were torn down, like this neighborhood near North Tryon.

Now, increasing traffic congestion and rising prices in the suburbs are driving people back into the city. High land values coupled with aging homes makes the economics work in favor of demolition over remodeling.

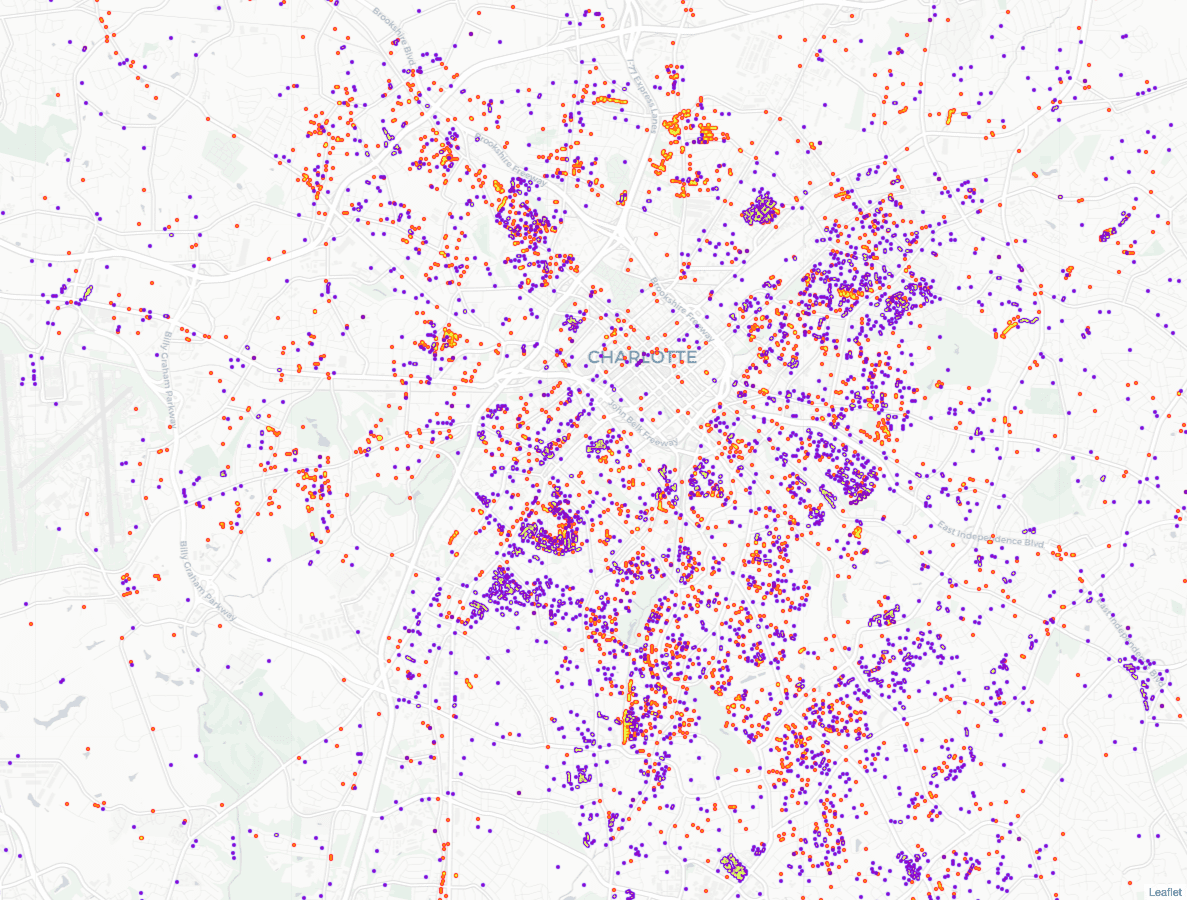

Recorded demolition Permits, 1999 to 2020, Charlotte. Orange represents demolitions on or before 2010, purple represents demolitions 2011 or later.

Pending demolitions?

With hundreds of older, lower-rent homes lost each year, record unemployment and the threat of mass evictions looming, many renters are facing a crisis.

Brookhill, a 36-acre community at South Tryon and Remount Road, is at the center of a struggle between the demand for new housing and the need for affordable housing. Average rent here is less than $500 per month, but the accommodations are substandard and the property has been neglected for years. Only about one third of the 400 homes are occupied — and a massive demolition and redevelopment project is on the horizon.

A plan for a new development at this site, known as New Brookhill, is underway. Plans include shops, retail and 324 apartments. More than half of the homes would be set aside for affordable housing. This means that many of the existing residents could stay at the site, if the plans win city approval and move forward.

The Hall House is a 12-story historic property at the corner of Seventh and Tryon. Formerly the Barringer hotel, it was constructed in Art Deco style and opened c. 1942. Operating as a hotel until 1975, It was eventually converted to a low-income senior living facility. Now, it sits vacant. Current plans call for its demolition to make way for a new 368 unit apartment building that would offer 110 below-market rate rental units.

Many buildings which are important historically or architecturally or fill the need for affordable housing will not survive based on their economic value alone. Unless more funding from the city or other sources is provided, buildings like the historic Hall House won’t be saved. It is up to local governments, and ultimately the citizens, to decide how much funding should go to preservation.

To Morrill, preservation “doesn’t belong on the cultural page, it belongs on the business page, because if you can’t make it work economically, what are you going to do?”

“Because ultimately, all of these historic places, they’re just real estate.”

The former Terrell Building At CPCC Central campus. Photo: Nathan Griffin  The old library at CPCC and Pease auditorium were demolished to make way for a new library and student center.

The old library at CPCC and Pease auditorium were demolished to make way for a new library and student center.  Old Warehouse near South Tryon St. Photo: Nathan Griffin

Old Warehouse near South Tryon St. Photo: Nathan Griffin  200 E. Woodlawn st., now demolished. Photo: Nathan Griffin

200 E. Woodlawn st., now demolished. Photo: Nathan Griffin  3232 South Boulevard will become a partial, adaptive reuse project called Platform 5. Photo: Nathan Griffin

3232 South Boulevard will become a partial, adaptive reuse project called Platform 5. Photo: Nathan Griffin  An old laundromat slated for demo to make way for new development. Photo: Nathan Griffin

An old laundromat slated for demo to make way for new development. Photo: Nathan Griffin  Homes and businesses on South Tryon being demolished. Photo: Nathan Griffin

Homes and businesses on South Tryon being demolished. Photo: Nathan Griffin  Clearing out existing homes to build luxury townhomes near Johnson & Wales. Photo: Nathan Griffin

Clearing out existing homes to build luxury townhomes near Johnson & Wales. Photo: Nathan Griffin

Nathan Griffin earned a master’s degree in economics from UNC Charlotte in 2018 and a bachelor’s degree in business management from Pfeiffer University in 2016. He works as a project developer at Trane where is involved in commercial construction projects. He is an Adjunct Instructor of Economics at Central Piedmont Community College.