Mapping banks & barriers: Visualizing financial disparities in Mecklenburg County

By Srajan Rastogi

As a high school student and as associate director of the National 4-H Geospatial Leadership Team, I’ve always been fascinated with how data is used to explore new avenues of growth and challenge for our communities. Living in Mecklenburg County, I’ve grown up surrounded by signs of economic progress. After all, it is home to more than 1.2 million people and, at its center, the city of Charlotte stands as a major financial hub, housing Fortune 500 companies and a booming business sector.

But behind this growth and prosperity, I began to notice challenges lurking in the shadows – especially for communities that do not receive the same spotlight on resources that their wealthier neighbors do. I looked beyond our progress and asked myself a simple question: in a region known for its growing banking sector, how many residents actually have access to financial services through these institutions?

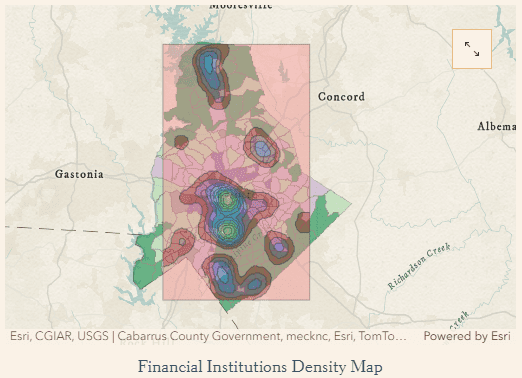

That very question sparked the beginning of my Financial Services Mapping Project. I wanted to explore where financial institutions—such as banks, credit unions, and insurance providers—are located across the county, and how that access correlates with the socioeconomic status of residents. The location of these services matters deeply, as limited proximity can make it exponentially harder for people to open accounts, access credit, build savings, or receive proper financial guidance without significant time or transportation burdens. My goal was to build an interactive map that will continue to help policymakers, community leaders, and advocates better understand these disparities and work toward more equitable access to financial services.

To start, I used ArcGIS and gathered data from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), the U.S. Census Bureau, and local government sources. For weeks, I researched data regarding every nook and cranny of Charlotte. Those efforts enabled me to manually create a layer of more than 350 financial institutions that I placed on top of census tracts. The tracts were categorized by low, moderate, and upper-income levels according to FFIEC standards. What emerged from this data was striking: the location of financial institutions strongly aligned with areas with higher incomes, leaving dozens of low-income communities outside the proximity of these financial services.

For example, large communities such as Dalton Village and Pinecrest, both located in West Charlotte, often have fewer than two financial institutions nearby, while some tracts have none at all. These areas are home to thousands of families who may need to travel longer distances for traditional banking services. In the absence of nearby options, some may even turn to alternatives like payday lenders or check-cashing services, which often carry high fees and less favorable terms. In contrast, more affluent areas like Fairmeadows in South Charlotte have six or more financial institutions nearby, providing residents with greater access to competitive rates, a wider range of services, and safer financial options.

This map is more than a visual; it’s a call to action.

By immersing ourselves in this data, we can better understand how inequity in financial services reinforces existing disparities and limits opportunities for upward mobility. Without access to nearby affordable banking options, it becomes harder for low-income families to save for the future and build credit, resulting in perennial cycles of poverty.

However, I believe there is hope. Every challenge presents opportunities for solutions. This work, combined with other insights from our geospatial community, can help local leaders pinpoint where to invest in efforts to expand access and advance discussions on financial equity.

For instance, improving transportation by upgrading existing routes or creating new ones can help families better access essential financial services. As a matter of fact, this work is already underway in some areas around Charlotte such as in the North End, where local advocates are focused on increasing mobility, connectivity, transit access, and economic development opportunities for their people. By continuing to plot modern trends of inequity and fostering community-driven efforts, we can help create real change and ensure every resident of Mecklenburg County, regardless of location, has the chance to achieve growth and prosperity.

About the author

Srajan is a rising senior at Levine Middle College High School in Charlotte, with plans to study business and public policy in the future. He is passionate about helping the community through organizations such as South Charlotte 4-H and enjoys applying tools like GIS to support local growth and development. Outside of school and volunteering, Srajan spends his time playing the viola and staying active with friends through various sports.