Affordable housing near Charlotte light rail? Still a challenge

As hundreds of apartments pop up around transit stations in Charlotte’s South End neighborhood near uptown, the city’s plan for more high-density housing near its young rail line is beginning to take shape. But a sister policy encouraging apartments for low-income families isn’t faring as well.

In the six years since the Lynx Blue Line opened, stretching 9.6 miles south from uptown to I-485, little publicly subsidized multifamily housing for less affluent households has been included in any of the South End apartments built near the historic Dilworth neighborhood or anywhere else along the route. City officials want to see more mixed-income housing, particularly as a northeast expansion of the region’s only light rail line gets underway.

After nearly two years of review, the Charlotte City Council recently adopted a revised policy for assisted multifamily housing near transit stations, in hopes of sparking more interest from developers in building mixed-income developments. However, the new policy exempts the areas along the city’s planned light rail extension and in a projected but unfunded transit line through southeast Charlotte. The revised policy also allows the subsidized multifamily housing in a new development to be clustered in a single building. The previous policy, adopted nearly six years before the rail line opened in 2007, required subsidized apartments to be scattered throughout a development.

It was the issue of allowing a concentration of subsidized units in one building that attracted the most debate among elected officials and community and business leaders worried about the potential impact. Council member Michael Barnes, who for eight years represented District 4 in northeast Charlotte, where new rail line will connect uptown to UNC Charlotte, vigorously opposed allowing a concentration of apartments for low-income families. (Article continues below.)

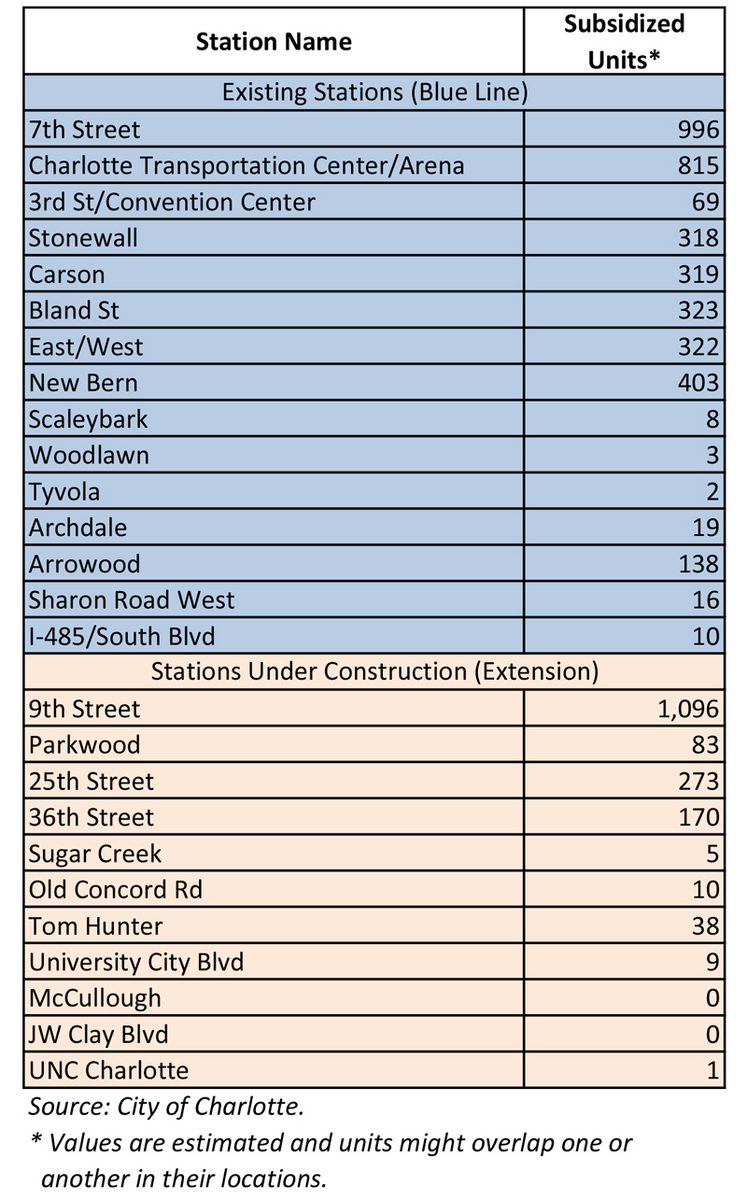

(The table, right, shows the estimated number of subsidized housing units within 1/2 mile of existing and planned Blue Line stations. The housing includes units in developments operated by the Charlotte Housing Authority as well as units rented by families using Housing Choice vouchers, known as Section 8, and in units built with Charlotte’s Housing Trust Fund.)

(The table, right, shows the estimated number of subsidized housing units within 1/2 mile of existing and planned Blue Line stations. The housing includes units in developments operated by the Charlotte Housing Authority as well as units rented by families using Housing Choice vouchers, known as Section 8, and in units built with Charlotte’s Housing Trust Fund.)

“My goal is to see the (Northeast) area elevate,” says Barnes, who in November was elected to an at-large seat and is now mayor pro tem. “There’s a lot of money that will be spent in that area with the Blue Line Extension and the (city’s) Capital Improvement Plan. The question is whether it will lead us where we want to be, with more quality residential, retail and office development. We should allow that market to develop naturally.”

The new policy, in some ways, is symbolic of the angst Charlotte faces as it tries to manage its growth and transition to a more urban environment. Some say the new policy seems to contradict a push toward scattering lower-income families among households earning more money. Others suggest it doesn’t go far enough to nudge more developers of market-rate apartments to take on the financial risks of mixed-income housing.

Charlotte joins an increasing number of cities across the country that are developing strategies to increase the supply of mixed-income housing near transit stations and throughout their communities. Supporters say that strategy offers low- and moderate-income families the benefits and savings of rail transportation and avoids a concentration of poverty, which can be accompanied by social problems such as higher crime rates.

Cities are exploring public-private partnerships and providing extra funding for affordable housing. In some cities, including nearby Davidson, ordinances require developers to include a percentage of affordable housing in new developments near transit stations or throughout the city. Some federal programs encourage more mixed-income development.

Over the past few years, Charlotte officials have aggressively pushed the idea of locating affordable and subsidized housing throughout the city, particularly in more affluent areas that lack it. But residents have strongly fought some proposed developments, and most of them did not win City Council approval. But Monday, the City Council approved a plan for 70 low-income apartments in an affluent south Charlotte neighborhood that strongly opposed the rezoning. It would be the first subsidized housing project in the council’s District 7.

Since the city’s Blue Line began operating, the nonprofit Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing Partnership, which specializes in serving low- and moderate-income families, has built the only mixed-income housing development near a station area, the 192-unit South Oak Crossing Apartments near the Arrowood Station. The Housing Partnership, with financial assistance from the city, is working with a private developer in a massive, planned mixed-use development near the Scaleybark Station, and is seeking state and federal funding to build additional subsidized apartments.

“If the city wants the new policy to be implemented, they have to think about incentives for developers,” says Ken Szymanski, executive director of Greater Charlotte Apartment Association. “The majority of market-rate developers are not likely to act, because mixed-income development is foreign to them and they have questions about financing and lending.” While the new city policy is beneficial, Szymanski says, city officials could entice developers and help them with high costs by contributing to such expenses as land and utility costs.

The revised policy on assisted multifamily housing applies only to projects that receive local, state or federal funding and it targets families who earn 60 percent or less of the area median income of about $64,100. As a part of the revisions, city officials reduced the maximum percentage of total assisted units allowed in a development from 25 to 20 percent and dropped a requirement that at least 30 percent of apartments be reserved for the lowest-income families, who earn 30 percent or less of the median income.

Additional subsidized apartments will not be encouraged within 1/2 mile of a transit station when more than 15 percent of the total number of housing units already in the area are subsidized units. Previously, that amount was 20 percent. The new policy retains a provision that subsidized apartments will be developed only as part of mixed-income developments and that they have the same appearance as market rate units.

The policy exempts the Blue Line Extension, a 9.3-mile, $1.16 billion route scheduled to open in 2017, and the Silver Line, a proposed but unfunded 13.5-mile rail or bus line from uptown southeast to Central Piedmont Community College’s Matthews campus along Independence Boulevard, because of “unstable market conditions.” A separate housing locational policy will apply to these areas, requiring scattering any subsidized housing in new multi-family complexes, although developers can seek waivers to put them in one building.

While the northeast area, home to University Research Park and UNC Charlotte, has experienced significant growth over the past few decades, Barnes and others expressed concern that too many low-quality apartments have been built, and that existing neighborhoods already provide a sizeable amount of affordable or subsidized housing. Some economically distressed neighborhoods along North Tryon Street need residential and retail revitalization, and by exempting the Blue Line Extension from clustering low-income apartments, Barnes says he hopes to see developers invest more in higher-end development near the transit stations.

Similarly, areas along Independence Boulevard in east Charlotte have struggled to attract commercial and residential development in recent years because of changing demographics. Planners admit that the less restrictive guidelines in the past allowed apartments with weak site design, few amenities and other problems. The guidelines for multifamily development have improved, they say, and new ones are being developed.

From 2000 to 2010, City Council District 4 in northeast Charlotte had the second highest amount (27.7 percent) of apartment construction after District 3 in southwest Charlotte (31.2 percent), which includes the fast-growing South End neighborhood. Apartment construction in those areas during that period accounted for nearly 60 percent of Charlotte’s multifamily construction. (Article continues below.)

Note: Since ranges are standardized across all maps, some maps do not have data in every category.

A part of the impetus for allowing the concentration of subsidized apartments in one building in a mixed-income development, which now will apply only to the existing Blue Line, is the city’s attempt to make it easier for developers to get federal and state funding and tax credits.

“It is a good policy,” says Dionne Nelson, head of Charlotte-based Laurel Street Residential, one of the leading mixed-income residential developers in the southeast. “It is a realistic acknowledgement of some of the structural challenges of successfully financing an assisted multifamily project. If Charlotte wants to be successful in delivering affordable housing in transit areas, we need as many tools as possible.”

As a result of a complex set of guidelines, Nelson says, it is less difficult for developers to win federal tax credits for assisted multifamily apartments when they are grouped in a single building, providing easier documentation that the credits are used only for the construction of assisted units. Similarly, it is less complicated to obtain financing from banks and other institutions when assisted units are not scattered next to market-rate apartments, according to Nelson and others in the building industry.

“In order to build affordable housing, you need a fair amount of federal help,” says John Porter, senior vice president at Charlotte-based multifamily developer Charter Properties. “When the residential uses get mixed, it’s more difficult to find banks who understand it.”

Charlotte planners say they’re optimistic about the potential of the revised policy.

“Our goal is to have more mixed-income development,” says Planning Director Debra Campbell. “We don’t think the issue is ‘Will you get affordable housing?’ The issue is more when you will get it. It’s not going to happen all at one time.”