Beyond the test score bump at Shamrock Gardens School

This article is a summary of a yearlong study to be published in an edited volume printed by Harvard Educational Press in fall 2014. The study uses administrative records from the N.C. Department of Instruction and Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, media reports, and in-depth interviews with parents, teachers, and administrators.

In 1997, when North Carolina launched its school rating system, Shamrock Gardens had one of the lowest scores in the state. The school looked as if it had been forgotten; school grounds were overgrown with weeds, paint peeled off walls; instructional materials were left over from previous generations. Staff turnover was high, scores were dismally low, and few people with options chose to work or send their children there. Soon after, the school became part of the state’s first efforts to take over failing schools.

In 2014, by contrast, school gardens are flourishing, the walls have fresh paint, the library is colorful and filled with computers and new resources, and parents are volunteering in classrooms staffed by highly effective teachers. Test scores have risen and enrollment is increasing. All the sanctions brought on by low academic performance have been removed, and a seven-year-old partial magnet program focused on “gifted” education has a waiting list. In 2013, Magnet Schools of America identified Shamrock Gardens as a “school of excellence.”

How did this dramatic change occur?

The challenges of school reform

School reformers generally have strong opinions about the importance of revising policies at the school level to accomplish change, but the evidence of such reforms is mixed. A recent Institute of Educational Sciences study revealed that 88 percent of interventions produced weak or no positive effects.[1] While there has been a tremendous amount of money devoted to determining how to turn around a low-performing school, the IES study shows that when it comes to improving educational outcomes, particularly in high-poverty schools, we have few strong evidence-based models. With the number of high-poverty schools increasing nationwide,[2] the need to better understand successful reform mechanisms for such schools is paramount. Shamrock Gardens provides a good case study.

The consensus from interview respondents for this study is that the majority of the reforms at Shamrock Gardens since 1997 did little to improve student learning. Because of the absence of evaluations of the reforms we will never know with certainty which reforms drove or stunted success of Shamrock Gardens. However, findings suggest several different efforts converged over 10 years to place Shamrock on a trajectory to success.

Today, standardized test scores measure school success or failure. By this metric, Shamrock has shown steady improvement from a composite rate on North Carolina’s End-of-Grade tests of 44 percent in 1998 to 67 percent in 2011. These scores are neither above the district average nor noteworthy compared to other schools with comparable student demographics—just under 90 percent low-income and more than 90 percent nonwhite. But on the ground, the school’s transformation has been dramatic—a new library, thriving gardens used for instruction, an active PTA, and a fully staffed school. Both white and black middle-class parents are enrolling their children for the first time in decades, particularly from the more affluent neighborhoods within the school attendance zone, therefore creating a more racially and socio-economically diverse learning environment.

So what happened?

While the district adopted the nationally prevailing focus on testing and prescribed curriculum and instruction at high-poverty, low-performing schools, Shamrock Gardens took a different path. While achievement was emphasized, school administrators also focused on building a stable, experienced staff. Supporters sought to reintegrate the school—hoping to attract middle-class families living nearby.

In addition to focusing on standardized test preparation (which can raise scores quickly), the Shamrock Gardens community began the difficult work of transforming school culture. In addition to improvements in the physical environment, changes have been made to the underlying educational infrastructure. They have included widespread use of rigorous curricula, a gifted magnet program integrated throughout magnet and non-magnet classrooms, small class sizes, data-informed instruction, engaged community and parent volunteers, strong leadership, and systematic teacher collaboration. Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools administrators have generally supported the changes, through increased flexibility and resources. School level improvements have led to changes in school culture and modest but steady test score increases, which together have slowly encouraged middle-class families to enroll, creating a more diverse learning environment. That virtuous cycle has become a success trajectory.

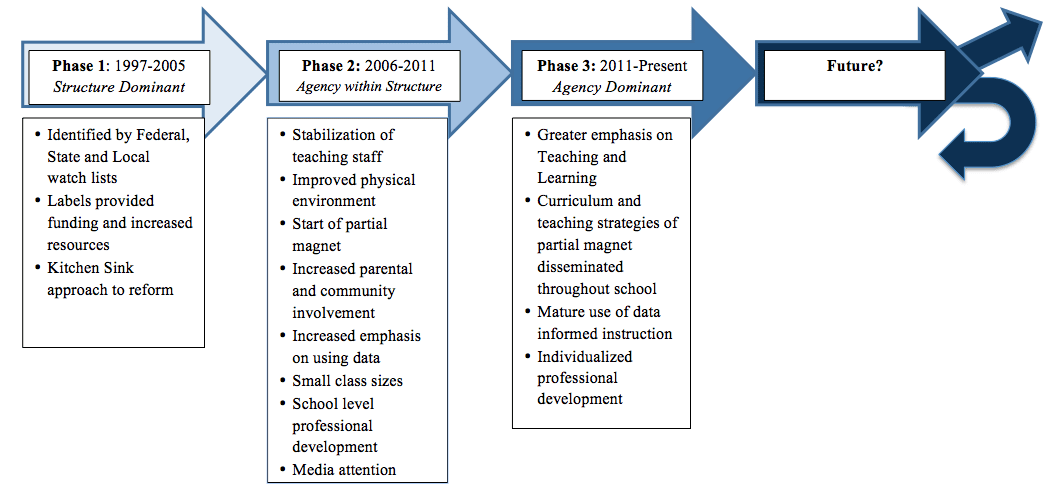

I describe this three-phase process in Figure 1, which presents the trajectory of Shamrock Gardens in phases. Phase I, 1997-2005, is dominated by structures imposed upon the school, including accountability-based labels and mandated reform efforts. That phase resulted in a high number of interventions, high cost and low success. Phase II, 2006-2011, was an important transition time, characterized by supportive structures and multiple initiatives by community members and staff. That was a period of many interventions, high financial costs, but continuous academic improvement. Today Shamrock Gardens seems to be moving into a Phase III. The accountability-triggered structures of Phase I have ended and many of the support structures of Phase II are no longer in place, both because of tightening state and local budgets and because the school no longer receives the money and district support that comes with low academic achievement.

With the improvements in place, today’s situation is one of continued efforts at the school level to improve academic achievement but with fewer interventions and lower per-pupil spending.

Findings suggest a relationship among the intensity and costs of interventions and their success over time. Reforms in Phase 1 were unsuccessful, but the approach in Phase 2 seems to have created a tipping point that led to the systematic school-level change of Phase 3. As the partial magnet matured, curriculum materials and instructional strategies were adopted in all classrooms, which led to stronger teaching instruction and academic outcomes across the school. Simultaneously, parent volunteers brought additional resources to support family nights, enrichment opportunities, and campus beautification. Even as district-level resources began to diminish, the culture and the parent volunteers remained. Taken all together, the pieces fell into place.

The overall finding is that the combined actions of many individuals, over time, within a supportive structure, set Shamrock Gardens on a success trajectory. Those reform efforts did not bear fruit in one year and did not originate from one person. Reform has taken time, sustained efforts, trust, strong leadership, adhering to basic educational principles (small class sizes, rigorous curriculum, data-informed and flexible instruction), teacher collaboration, community involvement, and district-level support. Most important, end-of-grade test scores cannot begin to adequately measure this dynamic process and, while important, cannot be the sole indicator of success.

While the Shamrock story provides a strong case study of sustained school reform within a large urban district, an important unanswered question remains: What will Phase IV look like?

More important, Shamrock Gardens’ story raises the question of whether its success can be taken to scale. Shamrock is a bit unusual, as a small school (typically less than 500 students) located in a naturally diverse school attendance zone. However, the individual pieces of the success trajectory are not elusive, and findings suggest that with sufficient district support, reform efforts can be replicated.

Given the demographic shifts in student populations nationally, the general political acceptance in districts such as CMS that it’s reasonable to have schools with concentrated poverty, and the legal framework in which today’s school leaders make decisions, Shamrock Gardens’ success provides an important case study of an approach to improving urban education that is feasible.

Figure 1. Shamrock Gardens’ School Success Trajectory

[1] “Randomized Controlled Trials Commissioned by the Institute of Education Sciences Since 2002: How Many Found Positive Versus Weak or No Effects,” Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy, accessed October 12, 2013, http://coalition4evidence.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/IES-Commissioned-RCTs-positive-vs-weak-or-null-findings-7-2013.pdf.

[2] “The Condition of Education 2013,” National Center for Education Statistics, accessed November 10, 2013, http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2013/2013037.pdf.

Amy Hawn Nelson is director of research at the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and directs the Institute for Social Capital.