Coronavirus highlights our digital divide

As much of our work, learning and lives move online following the stay-in-place policies to control the coronavirus pandemic, the inequity of the digital divide for low-income and rural households here and around the country is now more visible.

Like most states in the country, North Carolina has poor broadband (or high-speed internet) outside of most cities and towns. Almost all 100 counties in the state include rural areas with little or no broadband. (This map, showing the availability of broadband as reported by providers to the Federal Communications Commission, is considered under-representative.)

The lack of broadband accessibility and—just as significant—affordability (internet is more costly in the U.S. than most of the developed world; tech policy expert Susan Crawford explains why here) is not a new problem.

Technology has made it possible to do all kinds of activities at a distance, often for convenience: telehealth, remote work, e-commerce, digital learning. The pandemic makes the remote part a necessity, but if the internet was considered a convenience or a luxury before the crisis, it certainly isn’t now.

[Read all of our coronavirus content here]

Ross Danis, president of MeckEd, a nonprofit that helps at-risk high-school-aged youth identify post-secondary options, said “the structural inequities that have always existed are being magnified under pressure.”

There are multiple challenges to rapidly transitioning learning environments from school to home, as all districts in the state have done over the past month. He predicts the “achievement gap” for some groups will widen further still following the pandemic.

To blunt the impact, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools have worked to get devices such as Chromebook laptops and WiFi hotspots to families, but needs persist, Danis said. A recent Heal Charlotte survey of the Hidden Valley neighborhood in northeast Charlotte found that nearly 60 percent of households still do not have Chromebooks and 27 percent do not yet have WiFi access, he said.

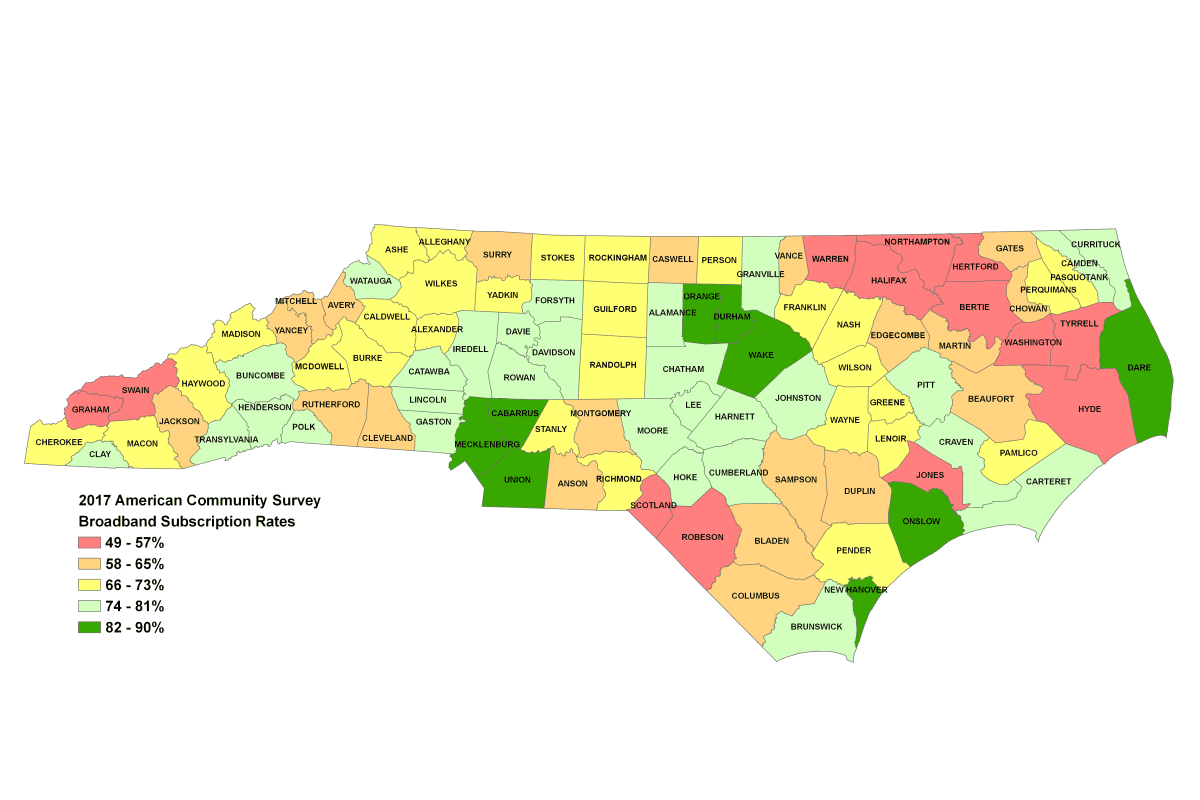

The North Carolina Broadband Infrastructure Office (NCBIO) estimates 20 percent of school-aged children statewide have poor or no internet service at home. According to 2017 ACS data, Mecklenburg, Cabarrus and Union counties had the highest average household subscription rates in the region, between 82-90 percent, while counties to the northwest averaged 74-81 percent, and Anson, Montgomery, Cleveland and Rutherford counties had average household subscription rates of just 58-65 percent.

These circumstances predate the pandemic, although there has been rapid mobilization to try to stem the immediate challenges. Providers have pledged to keep service running whether or not bills are paid (even as advocacy organizations have called for more generous interventions, such as the FCC expanding the ability of schools and libraries to distribute WiFi hotspots). Major providers in the Charlotte area, such as Spectrum and Comporium, are offering free service for 60 days to households with school or college-aged children.

One locally-based internet service provider, Open Broadband, said March was their company’s busiest month in terms of service requests, speed upgrades and new installations.

“This is a direct result of school-aged children being home, along with parents who are now required to work from home, and doctors moving to video teleconferencing,” said Alan Fitzpatrick, the company’s CEO.

In Wilson, North Carolina, which deployed the first publicly-owned fiber-to-the-home network in the state, Greenlight, a representative of the company said the focus, following the stay-in-place orders, became parts of the community where access was needed such as residential neighborhoods with high disconnection rates. The provider has added about a dozen additional WiFi connection points, beyond the public WiFi zones already available around town, to give households free internet access while home-bound.

“We’re doing this as a means of connecting households, so kids have access to digital learning and can finish the school year,” customer service manager Brittany Smith said.

Despite the rapid response of providers, it is important to consider why home-based internet adoption in certain areas is lagging. A new map from NCBIO shows how broadband adoption tracks closely with other measures of affluence: wealthier counties have higher levels of subscribers. Research suggests adoption is correlated to a range of issues beyond income including age, presence of children, access to computing devices and educational attainment, according to NCBIO. In this region, Mecklenburg County has an adoption score of 81.7, neighboring Stanly County scores 50.1, and Montgomery County just 14.

A dynamic map of adoption potential by Census tract presents a more nuanced picture: outside of wealthy urban neighborhoods, almost all areas of North Carolina would have greater broadband adoption if key barriers like cost and availability of service or devices are reduced.

In another map, also broken out by Census tract, the deficits in broadband availability and quality (defined as the share of population that can access fast speeds or have access to fiber internet, etc.) for some rural areas of the state are strikingly apparent.

Getting more and better internet access to people throughout the state is crucial, advocates say.

Dave Kirby, former director of Duke Hospital’s medical computing program and president of the North Carolina Telehealth Network Association, said in an interview prior to the outbreak that telehealth is substituting for in-person care as rural hospitals close. The 13-year-old nonprofit works to connect affordable broadband to remote healthcare providers.

Since the outbreak, care providers are quickly scaling up telehealth practices, while the federal CARES Act is directing millions of dollars to expand rural telemedicine applications. But there will be more to do long-term.

“Vulnerable populations will have limited ability to be monitored at home unless we solve the broadband problem,” Kirby said.

Although technology such as videoconferencing has improved in recent years, Kirby said, dial-up internet, satellite or cellular connections, sometimes the only options available in rural locations, will be inadequate to the need to provision healthcare remotely.

But overcoming the technology gap could resolve many related issues. Amy Huffman, with the NCBIO, said expanded telehealth is one way to break down the so-called urban-rural divide.

“The cool thing about telehealth is a patient in an urban center can be just as advantaged by remote monitoring [by their doctor] as a rural patient,” she said in an interview prior to the outbreak. Most telehealth transactions are currently between doctors based in urban areas and their rurally-located patients.

Meanwhile, Open Broadband’s Fitzpatrick said the company is working in “a safe manner” to install new service and get as many people connected as quickly as possible.

“A high-speed, unthrottled home internet connection has never been more critical,” he said.