From textiles to trails: A river’s changing path to prosperity

The South Fork of the Catawba is not the river Ted Reece remembers from his youth.

Reece, 91, can still picture the South Fork backed up to form a massive pool serving the Mays and Mayflower mills’ dyeing and finishing operations. It was wide and flat enough to land a seaplane — a spectacle he witnessed in 1938 or ’39.

“I probably saw the last one land,” said Reece. His father moved the family from their York County, S.C. farm to the mill village in 1922.

“It was full of fish,” Reece said of the river then, and deep. But it was also a dumping ground for the mills, and the cascade of dye waste they poured in gave the South Fork its nickname: “Rainbow River.”

Cramerton’s mills are long gone, as they are in most of the small towns that depended on textiles for generations. But Cramerton and other former textile towns are embracing the South Fork for what they hope is a new economic spark: outdoor recreation.

The Carolinas Urban-Rural ConnectionA special project from the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute |

|---|

The South Fork has not totally given up its wild ways. The river still occasionally floods, despite the dam just north in McAdenville, overtopping its banks and sloshing up to the new downtown businesses along Eighth Street and the park across the footbridge on Goat Island. Right now, though, the shallow, silty brown water flows calmly between its narrow banks below the dam, on its way to merge with the larger Catawba River near Lake Wylie a few miles downstream.

In 2007, Cramerton opened its first greenway, a 1.5-mile trail with a kayak launch called Riverside Park. A new, signature park across from downtown on 30-acre Goat Island followed in 2012.

That’s the year Floyd & Blackie’s opened. The coffee shop and ice cream store on Eighth Street rents canoes and kayaks straight out the back and directly onto the river.

“That’s one of the reasons I built this place — because I knew they were building that,” said owner Greg Ramsey, gesturing to the kayak launch and Goat Island. “It’s all working great together.”

One recent weekend, a group of a dozen paddlers rented all his boats. After their paddle, they spent hours on Ramsey’s lawn relaxing — while ordering food and cold treats. That’s the kind of spillover effect Ramsey, and the town, are counting on from the river’s proximity.

He said business has been rising sharply: 20 percent last year and 23 percent so far this year. Ramsey and his wife just opened a second Floyd & Blackie’s location, a bakery, in nearby McAdenville.

In 2015, a 365-foot pedestrian bridge to Goat Island opened, timed for the town’s centennial, and Cramerton is now linked to the regional Carolina Thread Trail network that’s set to grow in the coming years.

At the center of it all is the South Fork, recast from its industrial heritage as a “blueway,” running for more than eight miles from Spencer Mountain to Cramerton. The river that was once maligned, ignored and polluted is now seen as the town’s best asset.

“It used to be: Don’t worry about the river,” said Michael Applegate, director of travel and tourism for Gaston County. “Now, it’s the opposite. This is what we lead with. This is our front yard.”

Photo Gallery: See Cramerton’s transformation from textiles to trails.

Photo Gallery: See Cramerton’s transformation from textiles to trails.

Ramsey remembers the contrast.

“You couldn’t even see the river,” he said. The South Fork was screened by overgrown banks, out of sight from downtown Cramerton, and, except for the occasional flood or pollution warning, out of mind.

Other mill towns like Belmont, McAdenville and Lowell have embraced the philosophy of making the river their front door, on both the South Fork and the main Catawba River. Applegate said the county has been investing more in promoting the rivers as recreational resources to draw people from the region, as part of its “GO Gaston” campaign (short for “Gaston Outside”). Gaston made maps of the rivers for paddlers and, this summer, created a new promotional video of paddling on the South Fork.

Jeff Ramsey, Greg’s brother, was a town commissioner from 1994 to 2008, when the initial decision and planning were completed to fund a riverside park and trail. Turning to the river has been key for Cramerton and nearby communities, he said.

“Gaston County is really transforming from one thing, textiles, to all these small towns trying to find their own identity,” said Ramsey.

Cramerton’s population has more than doubled since the 1980 Census, when it bottomed out at just below 1,900. Now, more than 4,400 people call Cramerton home, according to the latest estimates.

Floyd & Blackie’s, in downtown Cramerton. Photo: Nancy Pierce.

The town’s revival can’t be attributed solely to the river, of course. Ramsey, Reece and others also point to well-regarded local schools, cheaper housing, proximity to booming Charlotte, and crucially, Charlotte’s airport.

There’s evidence of rapid growth all along the South Fork. Hundreds of apartments loom over the river. Another phase of the South Fork Village development is going up fast, with acres of raw, red dirt exposed by the earth-movers. The beeps, clanks and roars of construction equipment float across the river, intermittently visible behind the trees left as a buffer between new development sites and the water.

Threats remain

Though the dye-dumping days are long over, quashed by the 1972 Clean Water Act, the South Fork is still a threatened waterway. Now, the threats are largely runoff and bacteria. Catawba Riverkeeper Brandon Jones says it’s the very growth of nearby communities that now makes for the biggest danger.

“When you have more people, you have more impervious surface,” said Jones. And more impervious surface means more runoff, which carries sediment and other pollution into the river.

With most large, single-point polluters (like water treatment plans) now monitored and controlled, the biggest challenge in eliminating bacteria is leaking septic systems scattered in thousands of backyards — which are unmonitored and extremely difficult to track. In water monitoring tests this summer, the river near Cramerton exceeded e. coli limits for safe swimming 20 percent of the time, far more often than nearby swimming spots on the Catawba and its lakes.

“It’s a little bit from this pipe, a little bit from that backyard,” said Jones. He spent the summer conducting monitoring tests on one small tributary of the South Fork that consistently showed high bacteria levels, but was never able to locate the source.

Turbidity, a product of silt in the water, is another persistent problem.

“You’re not going to see trout in the South Fork,” said Jones. “Improving the water from a turbidity standpoint, from a bacteria standpoint, is going to be a long-term project.”

But, he adds: “It’s still great to paddle. And it’s a lot better than it was 50 years ago.”

Construction at South Fork Village in Cramerton. Photo: Nancy Pierce.

The Catawba Lands Conservancy has protected big chunks of the South Fork’s shoreline. The conservancy, which leads the Carolina Thread Trail, traces its first major investment to the area: The Redlair Preserve upriver from Cramerton flanks the South Fork. When it was first preserved in the early 1990s, the conservancy’s holdings totaled just 75 acres. Redlair added 750 acres to the conservancy, and now totals about 1,550 acres.

“It’s been one of our main efforts for years,” Matt Covington, director of land acquisition, said of the South Fork.

As they work to persuade more landowners to donate easements for trail access and preservation, Catawba Lands Conservancy executive director Bart Landess said they’re finding local officials and developers more receptive.

“It’s an economic development play,” said Landess. “The towns are just really embracing this.”

The group ultimately hopes to acquire Spencer Mountain (they already have the money lined up), expand access for paddlers and extend the riverside trail to a total of more than 12 continuous miles.

“It used to be a situation where people turned their backs to it,” said Bret Baronak, director of the Carolina Thread Trail. “Now, the river’s an asset, not something you ignore.”

A ‘benevolent dictator’

The original mill was built in 1906 by a group of Charlotte investors — an example of the importance of regional connections and capital flows in the early 20th century. A century ago, Cramerton was a very different place: a compact mill village known as Mayworth, filled with people who worked together, played baseball together, lived together and went to church together.

“You lived in probably a three-mile square, and didn’t leave it,” said Reece.

Stuart Cramer, the investor who came to own it all, made sure he had talented players on his team when they played against the surrounding mills.

“Man alive, talk about baseball. When there was a ballgame, the whole town would turn out,” Reece said. “Cramer never paid anyone to play ball, but if you were a good ballplayer, you got a good job. That was how he worked that.”

The Mays and Mayflower mills in Cramerton, both of which closed in the 1970s and were since demolished or destroyed by fire. The South Fork of the Catawba River has been diverted to form a wide pool to serve the dyeing and finishing operations. Waste dumped in the water gave it the nickname “Rainbow River” for decades. To the left of the train tracks, the dormitory for single, male mill workers is visible; above those, some mill houses can be seen. Photo courtesy the Millican Pictorial History Museum in Belmont.

Cramer built a dormitory for single men, a lodging house for the female teachers he recruited to the school for mill children, a swimming pool, movie theater, athletic facility and shops that sold goods to the workers. Overlooking it all, Cramer built himself a manor named Maymont on the nearby hill that’s now called Cramer Mountain. Cramer was a “benevolent dictator,” Reece recalls, his hand visible in everything that happened in the mills and the surrounding village.

For farm families like the Reeces, used to being in debt and struggling against nature every year for an uncertain crop, the mills represented an unprecedented economic opportunity.

“Cotton was the cash crop, but the boll weevil came along and ate the cotton,” Reece said. “They were destitute.”

His father never came to like working inside all day, his hours set by a manager, but he appreciated the steady pay and path out of poverty the work offered.

“This was something new to him, a farmer, broke all the time: Work a week, have money in your pocket the next week,” he said.

Photo Gallery: Knitting together the region with the Carolina Thread Trail

Photo Gallery: Knitting together the region with the Carolina Thread Trail

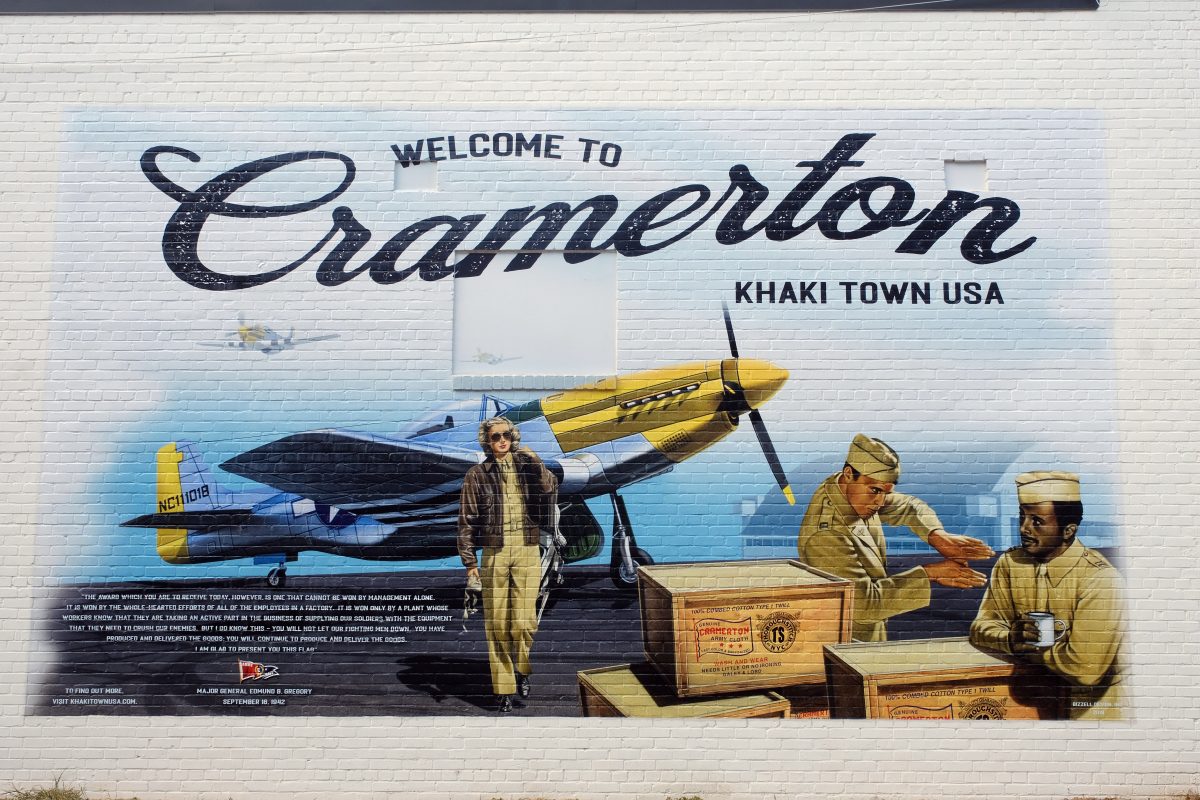

At their height during World War II, mills in Cramerton pumped out the tough khaki that clothed U.S. soldiers — invented by Stuart Cramer, a member of the War Production Board. He allowed other mills to produce his patented cloth to aid the war effort. Today, a statue and mural downtown pay tribute to that legacy, which still swells Reece’s voice with pride.

“There was tremendous loyalty,” said Reece. “A lot of people wouldn’t buy anything unless it was made in Cramerton.”

Reece worked in the mills for summer wages when he was a high school student in the 1940s, before joining the army. He earned 90 cents and hour. After college at Belmont Abbey, he went on to work in Cramerton’s mills for more than three decades.

The town’s good times continued for a couple of decades after Burlington Industries bought the plants in 1946. Cramerton became an incorporated town in 1967, as Burlington sold the mill village houses to individual families.

But decline crept in. The Cramerton Train Depot was taken out of service in 1969. By the 1970s, offshoring gained momentum and the textile industry was leaving. Burlington closed the Mays mill and part of another mill in 1975, eliminating 800 jobs — more than half the town’s textile employment. The Mays building was razed in 1977.

When the Mayflower plant and the town’s third mill closed just a year later, in 1978, the remaining jobs disappeared as well.

“This was a dead town,” said Jeff Ramsey, whose parents and grandparents worked in the mills. “We didn’t have any money to reinvest in our community.”

The loss of local jobs also tore at the social fabric in subtler ways. People had to move away or accept long commutes to find work, and the close-knit community frayed.

“For 100 years, a majority of people worked in Gaston County, because we had the jobs,” said Jeff Ramsey. “Then, you basically had the city of Cramerton having to get in their cars to drive to work.”

Many residents still commute to work in Charlotte or other locations – Gaston County sends a net 24,000 workers to Mecklenburg County every day.

Floyd & Blackie’s owner Greg Ramsey, helping in clients. Photos: Nancy Pierce.

But the first hint of revival came in 1986, when a new golf course called Cramer Mountain Country Club opened. Upscale houses along the course soon started selling. The town had a growing tax base to work with, and started planning investments in long-neglected infrastructure — like the trails and parks they’re now counting on to drive growth.

The population slowly rebounded, hitting almost 3,000 residents in the year 2000, and passing 4,100 a decade later. Now, Reece said he sees more new residents, children and, crucially, a sense of identity reemerging in their town.

“I see youth all around me,” said Reece. “Young people, families.”

Applegate said regional connections will be crucial to the success of Gaston towns as they pursue recreation-based development and branding. Luring people from bigger population centers, especially Charlotte, to spend their money is key — but Applegate said that’s getting easier.

“Sometimes, people treat the Catawba River like it’s this Great Wall of China,” he said. “There have been so many newcomers, and so much explosive growth, that I think naturally, over time, those barriers are breaking down.”