David Walters, a voice for urbanism, retires from teaching

When David Walters moved to Charlotte in 1990, you could pretty much fit all the people here who understood urbanism into one room. And when that happened – for instance, at the loosely organized Charlotte Urban Forum breakfast group – Walters was generally right in the thick of it.

He’s been in the thick of it pretty much ever since.

Challenges for N.C. planning?Walters describes the three big changes he would make for North Carolina. Read David Walters’ articles for the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and PlanCharlotte.org. |

When you list the many people in Charlotte who’ve been prodding this suburban-form agglomeration of subdivisions, strip centers and cul-de-sacs to grow into a real city, Walters should be among those at the top of that list.

Sure, plenty of others have also been key players – I don’t intend to demean their contributions. But Walters has been influential and outspoken for a quarter of a century, while wearing multiple hats: as a professor and trainer of young planners, as a practitioner and as a pundit – or as he calls it “an active, pushy professional.”

In early May he’ll teach his last official class as a UNC Charlotte professor in the School of Architecture’s Master of Urban Design Program, which he’s headed since it admitted its first students in 2008. He’ll continue to work as a planning consultant with The Lawrence Group’s office in Davidson, which he’s done since 1999.

Walters arrived at UNC Charlotte in 1990. I met him a few years later, after I had joined the Charlotte Observer’s editorial board and begun writing opinions after years as a news editor. I wrote a few op-ed columns about neighborhoods, describing how the large lawns and drive-everywhere patterns in my suburban neighborhood felt isolating. I’d heard of an emerging planning movement called New Urbanism, and as I got to know planners and developers in town, it was clear this British fellow at UNC Charlotte knew as much or more about New Urbanism as anyone. Over the years he was immeasurably important in helping me understand the way seemingly small details like street widths and building heights and the angles of street corners work together to shape the larger experience of our daily human lives.

Walters always made the salient point, often lost amid criticism of New Urbanism, that New Urbanism is really Old Urbanism. It applies timeless principles that have shaped cities for centuries, only it applies them to new as well as existing places. It’s really just Urbanism, he said.

Walters always made the salient point, often lost amid criticism of New Urbanism, that New Urbanism is really Old Urbanism. It applies timeless principles that have shaped cities for centuries, only it applies them to new as well as existing places. It’s really just Urbanism, he said.

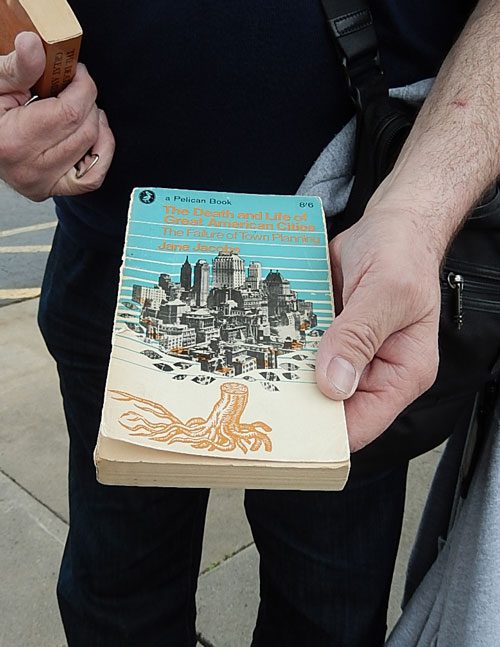

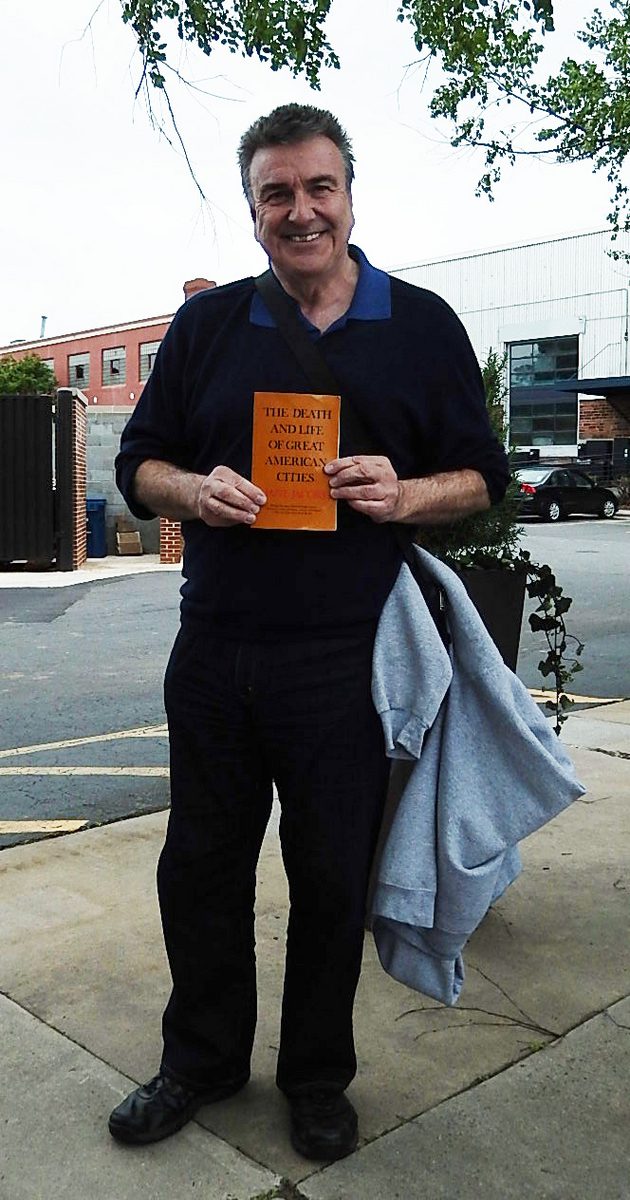

That view has sometimes put him crosswise, philosophically at least, with the predominant Modernist tilt in 20th- and early 21st-century architecture. As an architecture student in the 1960s in Great Britain, he recalls, he was forbidden by a male professor to read Jane Jacobs’ 1961 The Death and Life of Great American Cities, now considered a masterwork. The professor scorned the author as “not a planner, not an architect and a woman.” Of course, that made Walters read it even more avidly.

“I was educated as a Modernist,” he said, “but from graduate school on, as a community activist, everything I’ve done has been to subvert the Modernism Jane Jacobs attacked.”

“I was taught to reject context because it wasn’t worth a damn. It was old. It would inhibit creativity.”

But he said, the result of “getting rid of the context” led to getting rid of people’s homes, even whole neighborhoods, as part of urban renewal and other city planning tools of the 20th century.

Nor has he mellowed on his aversion to Modernism as an architectural movement. “Modernism has us in an arm lock, still,” he said. The movement “is alive and well in its fetishism of the object.”

Jacobs’ influence in his professional work is clear: Must of what he has done has taken place at the intersection of urban design, town planning and community participation.

Additionally, his regular writing for the Charlotte Observer’s op-ed pages and numerous letters to the editor, combined with 10 years as a columnist with the alt weekly Creative Loafing, have spread his influence beyond the sometimes insular world of planners, developers and architects. When I mentioned Walters’ retirement to Lisa Shepard, my office manager at the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, she said she’d been a regular reader of his columns, and noted, “Even though he doesn’t know me from Adam, he’s had an effect on me.”

Walters’ role in Charlotte and the Carolinas has attracted little of the celebrity glow that surrounds building-as-icon stars like Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid, or the ubiquitous New Urbanist contrarian, Andres Duany. Instead, Walters taught class after class of planners and urban designers how to create neighborhoods people will want to live in. Probably the most famous of his students to date is N.C. Lt. Gov. Dan Forest, whom Walters taught as a third-year architecture student. (“He was a very good third-year studio student,” Walters recalled.)

Other students include:

- Ann Hammond, a former Charlotte City Council member who went back to college to learn planning and became planning director for Huntersville, then a top officer at the Nashville, Tenn., Metro Planning Department.

- Tim Keane, formerly Davidson planning director, now director of the Planning, Preservation and Sustainability Office for the City of Charleston.

- Tim Brown, Mooresville senior planner.

- Michael Dunning, a principal with Shook Kelley Design.

- David Ravin, owner of The Vue, a residential tower in uptown Charlotte, formerly with Crosland, a major Charlotte development company.

Dunning and Ravin were instrumental in developing Huntersville’s acclaimed, mixed-used Birkdale Village. Birkdale draws designers and planners from around the world to see how a mixed-use, main-street-type development can be built in what would otherwise be low-density suburbia.

“I had helped write the code that made Birkdale happen – with Ann Hammond,” Walters said.

Writing code is not something that wins architects the Pritzker Architecture Prize. But for enduring and widespread effect it may well be more important than designing single buildings, no matter how spectacular.

The codes Walters helps write replace aging zoning ordinances dating to the mid-20th century that usually enforced the drive-everywhere blandness of U.S. suburbia since 1970. Walters was instrumental in writing new – and New Urbanist-influenced – codes for Davidson, Cornelius, Huntersville, Mocksville and Locust. Among his many other plans in this region are: the Downtown Gastonia Master Plan (the first vision plan for reviving downtown Gastonia), a Gastonia greenway plan, and the Firestone Mill Village Plan for the west Gastonia neighborhood around that now-redeveloping mill. He was a primary author, as well, of The Mountain Landscapes Initiative Toolbox, a comprehensive documentation of progressive policies and precedents for building sustainably in mountain terrain.

The College of Arts + Architecture has announced the first endowed scholarship in the Urban Design program. It’s name: the David Walters Endowed Scholarship in Urban Design.

Mary Newsom is associate director of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and directs the PlanCharlotte.org website. Disclosure: She has known David Walters since 1994 and has partnered with him on numerous projects, discussions and public events.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and may or may not be those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.