An ’80s tale: How rural preservation didn’t happen

[highlightrule]Choices made decades ago ruled out the preservation of large-scale green belts or farmlands in Mecklenburg. This is the story of how that came about. [/highlightrule]

You can drive south down Dixie River Road beyond the venerable Dixie Grill & Grocery and for 2 miles you’ll see only woods, a few driveways and the scattered small houses typical of rural, farming areas of the Carolinas. Head a mile and a half down nearby Sadler Road, and you’ll see almost nothing but woods until you come to a row of houses strung along the Catawba River shore.

This big chunk of undeveloped land west of Charlotte Douglas International Airport is more like Mecklenburg County circa 1966 than 2016. But changes are coming as decades of development pressure keep gobbling up the county’s final remaining expanses of significant rural acreage.

Much of this big chunk of west Mecklenburg between the airport and the river – almost 1,400 acres of it – is proposed for a huge mixed-use development along the east bank of the Catawba. The area is so large and the proposed development so extensive that at the Oct. 17 public hearing on the rezoning request, several Charlotte City Council members begged for more time to study it, including council member Patsy Kinsey, who said, “I’d certainly rather eat this elephant one bite at a time.”

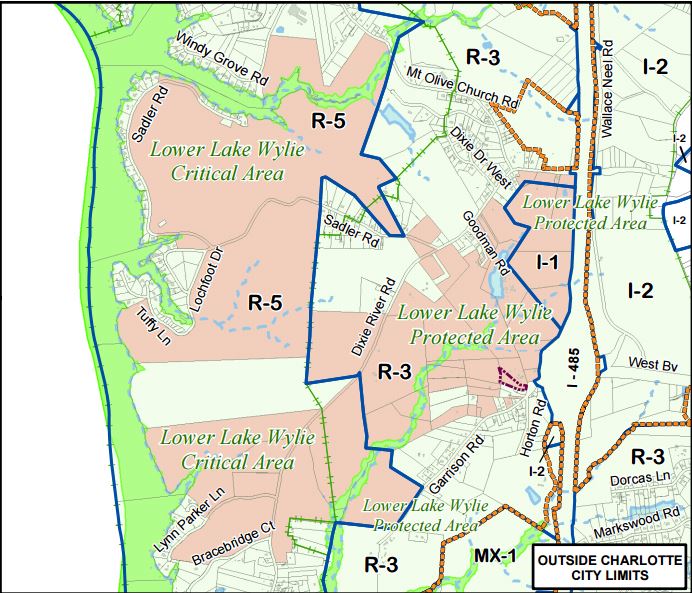

Map shows, in pink, the area proposed for the River District development. Image: City of Charlotte

If council members eventually approve the proposal, Mecklenburg County will lose one of a handful of large areas that remain undeveloped – areas that are still what most of us would call rural countryside. Not counting scattered farms and undeveloped woods, plus some land-trust-owned or publicly owned parks and preserves, the other major undeveloped sections are the county’s northeastern corner east of Davidson, the point of the county east of Mint Hill, and an area near Gar Creek between the northwest section of I-485 and Mountain Island Lake.

And one of those sections – the Davidson rural area – is now covered by a new plan that proposes new development and sewer service in the area.

Why are those the county’s only remaining large areas not covered with subdivisions, shopping centers, streets and office parks? The answer is complex, but one key factor is policy choices made decades ago. Thirty years ago Mecklenburg County could have opted for a different path, setting aside some parts of the county as rural land or greenbelts.

It didn’t. This is the story of some significant choices made then that continue to shape life and development in the county today.

WHY DEVELOPMENT GOES WHERE IT GOES

The answer to why some areas develop and others don’t is complex and includes historic patterns, land values, public perceptions, highway locations and large operations like airports. But municipal sewer service plays a powerful role, summed up by a planners’ cliché: Growth follows the pipe. Sewer service allows for more intense development than septic tanks. And for now at least, those four areas are the county’s last remaining sections without sewer service.

That will change. Charlotte Water, the city agency that builds and runs the sewer system, operates on a policy to provide sewer service where government-approved land uses require it. It is already planning to work with developers to extend sewer service to the River District development, should the project win City Council approval. Davidson, also, is making plans to ask for sewer service to its rural area. Mint Hill also supports bringing sewer, where possible, to its undeveloped areas.

Eventually – barring some unforeseen crash in the area’s housing market – as sewer arrives those undeveloped sections will sprout streets, houses and other development just like the rest of the county, although Davidson’s newly adopted rural area plan maintains the town’s earlier goal of 50 percent of the rural area being protected as open space.

TOPOGRAPHY MATTERS

To see why some parts of Mecklenburg still lack municipal sewer service, you have to start with the land itself. The area’s creeks, rolling hills and valleys may mean little to city-dwellers unless a bike ride up a hill makes them pant. But sewage systems follow a basic truth: Water flows downhill.

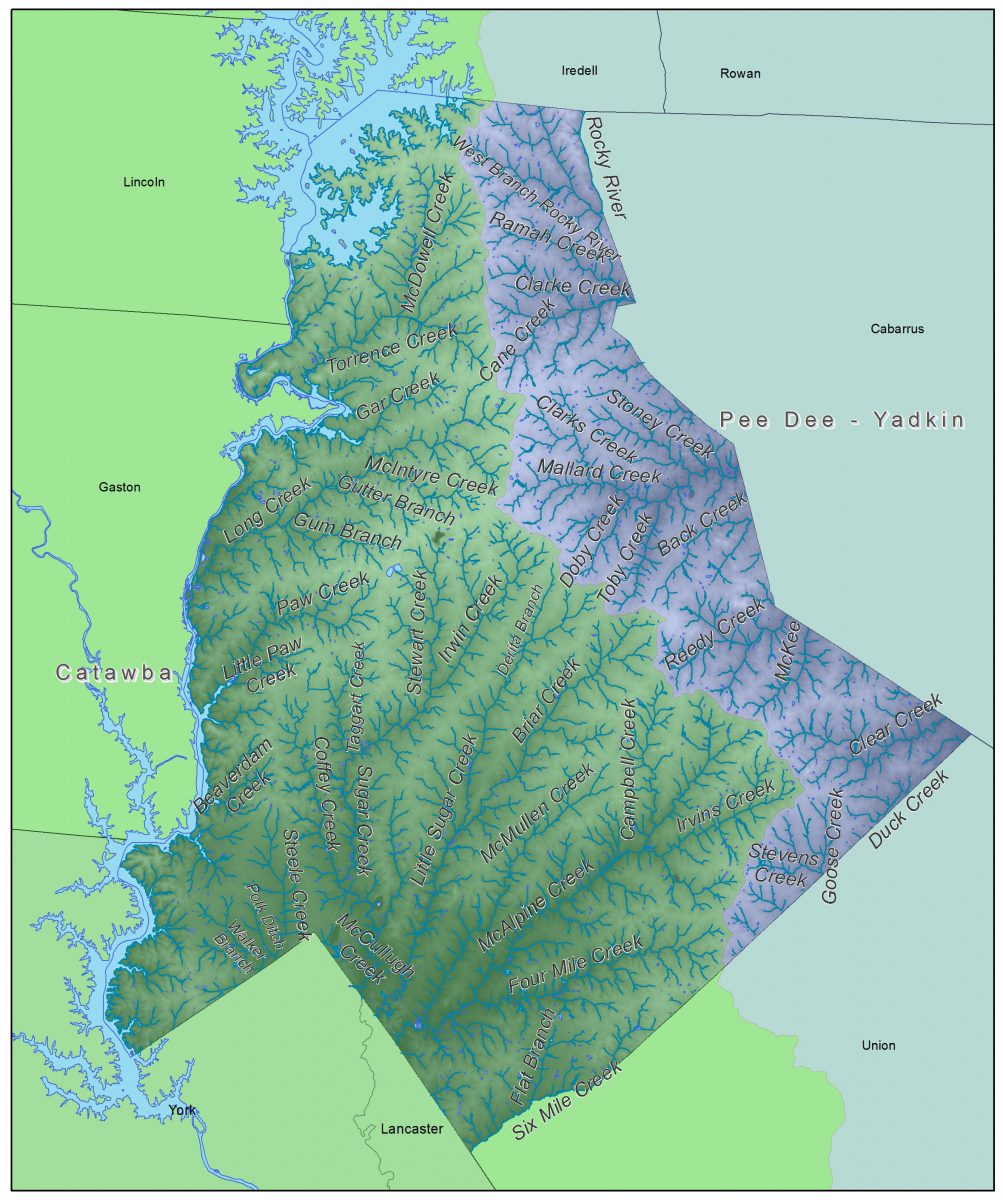

The river watersheds of Mecklenburg County. Green area on the left is in the Catawba River basin. In the purple area at right, water flows into the Rocky River, part of the Yadkin-Pee Dee basin.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s sewer system depends on gravity to send sewage in the pipes downhill to treatment plants, so many main sewer lines run beside the county’s many miles of creeks. It’s not impossible, but it’s more expensive to build lift stations to pump sewage over a ridge. Furthermore, anti-pollution regulations mean a waste treatment plant must discharge into a lake, river or creek large enough to absorb treated wastewater without excessively fouling the water.

A ridge lies between the undeveloped land west of Charlotte’s airport and the nearest sewage treatment plant. Another ridge, running through downtown Davidson, splits north Mecklenburg County into two river watersheds. To the west, water flows toward the lakes on the Catawba River and on the east it flows toward the Rocky River. All but one of Charlotte Water’s sewage treatment plants flow into the Catawba basin. So areas east of that river watershed divide have been tougher to serve with sewage plants, often requiring agreements with Cabarrus County’s utilities. That watershed divide also runs through eastern Mint Hill. In the eastern part of town, water flows toward the Rocky River and away from Mecklenburg’s sewage treatment plants.

Homes can use well water and septic tanks, of course. But Piedmont soils tend to be thick clay, so in some areas septic tanks require lots as large as an acre or more. Without municipal water-sewer service, standard single-family subdivisions and large-scale commercial development are generally impractical.

PROTECTING RURAL AREAS

Once a sewer line is built, says UNC Charlotte Urban Institute’s Director Emeritus Bill McCoy, who has observed and researched growth in the Charlotte region for decades, “The opportunity to do anything else that is not development, like preserve open space, is pretty much doomed.”

That’s why some communities use municipal utilities as a tool to protect farmland and other undeveloped areas from development. Those communities concluded it’s more cost-effective to focus development where water-sewer service already exists rather than providing it throughout the county.

That’s what Cabarrus County did. The county just northeast of Mecklenburg grew from 85,895 residents in 1980 to today’s 196,762 (compared with Mecklenburg’s growth from 404,270 to 1,034, 070 residents). Reeling from the population influx, Cabarrus 10 years ago adopted a plan to keep some areas rural and agricultural. To support that vision, the county’s municipalities enacted unified development ordinances that used zoning to support that plan. They agreed not to extend public utilities into areas the plan designed as rural. “It’s working well,” says Jonathan Marshall, deputy county manager, who helped create the plan. “The cities are really concentrating on their core. … I think they see the benefit of having the development where they have the services.”

[highlight]“The cities are really concentrating on their core. … I think they see the benefit of having the development where they have the services.” — Jonathan Marshall, deputy Cabarrus County manager[/highlight]

Cabarrus’ zoning also forbids private sewer plants for subdivisions in areas zoned rural.

Again, topography matters. One factor that supports the plan, Marshall says, is that soils in rural eastern Cabarrus County make septic service rough even with zoning allowing only one house per 3-acre-lot. Additionally, that area is underlain by a slate belt, he says, so shallow soil is another problem for septic tanks.

Similarly, Orange County in 1987 created an urban service boundary to protect rural land east of Chapel Hill and Carrboro. Hillsborough signed on in 2010. The municipalities agreed not to extend public utilities to the area. Developments in that area must use septic tanks, says Craig Benedict, director of the Orange County Department of Planning and Inspections. Because, again, the soils aren’t conducive to septic tanks, typical lot sizes are 2 to 5 acres. Subdivisions in the rural area are usually under 20 units, he says, and many are less than six units.

Winston-Salem-Forsyth County not only adopted a countywide strategy not to put sewer service in rural areas on the edges of the county, but in 1984 it created a program using public money to buy development rights. The program, which protected about 1,700 acres and 27 farms, was the first such program in the Southeastern U.S., says Planning Director Paul Norby. Although that program isn’t operating any more, the city-county comprehensive plan, Legacy 2030, reinforces the policy of not extending municipal services.

“We did a report for the county commissioners about four years ago that said the most effective way to keep the rural areas rural was to not run public sewer out there,” Norby says. He adds, “So far, this has held.”

Most of the rural area is an agricultural zoning district with a minimum lot size of 1 acre, “which isn’t much of a restriction, but combined with no sewer and poor soils, it helps,” Norby says.

MECKLENBURG CHOSE ANOTHER PATH

Thirty years ago, some in Charlotte-Mecklenburg tried to use similar policy tools. For a short time in the 1980s the Charlotte City Council tried a policy to not extend sewer service south of N.C. 51, as a way to push growth into other parts of the city. But subdivision developers simply got permits from the state to build private waste treatment plants. Eventually the city dropped the policy. (Today, officials say, those private plants are more difficult to build.)

Some residents and officials, seeing farms and rural areas fall to rapid suburbanization, talked of trying the tools other cities were wielding to try to stop sprawl. The aim in those areas was generally twofold: to create areas of undeveloped, rural green space outside cities as a way to ease the expense of providing public services, and to propel denser growth into their centers after decades of suburbanization and white flight.

One important but little-remembered Mecklenburg effort failed – but only after what looked like success. Owen Furuseth, who retired last summer as associate provost of Metropolitan Studies at UNC Charlotte (disclosure: he oversaw the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute), in the 1980s was a professor in the university’s Geography Department and served on the county Soil and Water Conservation District. That role put him at the center of a surprising, grass roots campaign to save farmland.

As Furuseth recalls, the then-chairman of the Mecklenburg Board of County Commissioners, Fountain Odom, was concerned about farmland preservation and won a spot on the 1986 county bond referendum for $10 million in bonds to be used to buy development rights from farmers who wished to sell. Buying development rights is a fairly common tool around the county, which gives a cash infusion to farmers who want to sell the rights and protects land from future development. It’s strictly voluntary on the part of the land owners.

Odom collected a small group of people including Furuseth, who notes, “I was from Oregon and he knew what was going on in Oregon in terms of open space preservation.” Oregon in 1973 adopted what many other nations use, legally enforced urban growth boundaries that bar most development outside the boundary.

This small bond committee – unsupported by the typical Charlotte Chamber and business community bond advocacy campaigns – ran a low-key effort. “I bet we didn’t spend more than $500,” Furuseth recalls. “We printed up these little signs with a red barn. … We made these posters and we went around on Saturday mornings and put them around the county. And that was the sole campaign.”

The farmland preservation bonds passed.

[highlight]“The movers and shakers decided then … Mecklenburg County was going to be all urbanized. If you wanted rural, go to Gaston County or go to Cabarrus.” — Owen Furuseth, retired associate provost at UNC Charlotte[/highlight]

But, Furuseth recalled in an interview on the subject in 1997, “From that point on, the developers basically squelched it.” In a recent interview, he recalls that after the bonds passed, the board of county commissioners changed membership. “The county commissioners at that time basically sat on it and just said, ‘We don’t have to sell those bonds,’ Furuseth says. “They essentially sat on it until the authorization [to sell the bonds] expired.”

The upshot of those decisions, he says, is that “the movers and shakers decided then … Mecklenburg County was going to be all urbanized. If you wanted rural, go to Gaston County or go to Cabarrus.”

ANOTHER INITIATIVE STYMIED

A later, different effort to preserve rural areas was also stymied. In 1999 a Huntersville initiative aimed to preserve rural land outside that fast-growing north Mecklenburg town by creating a voluntary transfer of development rights program. In such a program, used by more than 100 places in the U.S., developers could buy rights from farmers willing to sell and use those development rights in a part of town where officials hoped to channel growth.

Development advocacy groups including Charlotte’s Real Estate and Building Industry Coalition and the N.C. Home Builders Association fought that proposal, which needed an OK from the N.C. legislature. The bill that had been introduced died.

RURAL PROTECTION IN NORTH MECKLENBURG

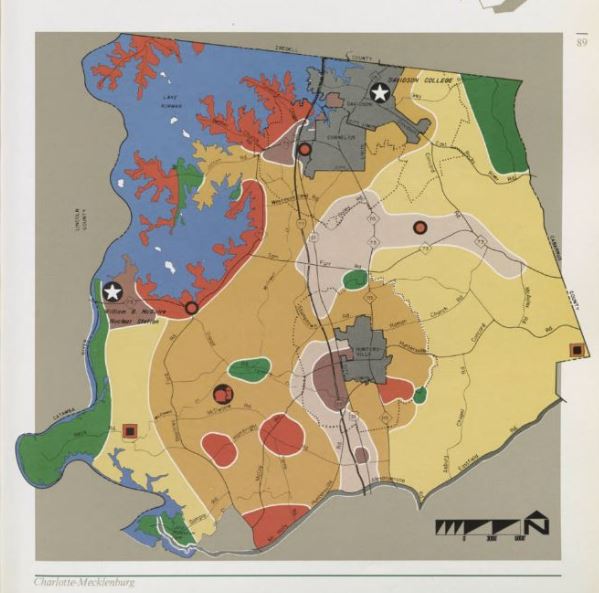

Map from page 89 of the city-county 2005 Plan, adopted in 1985, proposes a state park for northeastern Mecklenburg. Image: Atkins Library Special Collections, UNC Charlotte

But several rural protection plans went into operation, at least for a time. The towns of Huntersville and Davidson in the 1990s adopted plans to keep the areas east of town rural. Those areas until recently lacked sewer service. But that’s changing. More sewer service is coming to the area east of Huntersville with two lines under construction and an existing pump station, according to Barry Gullet, Charlotte Water director. The utility has an agreement to use a treatment plant in Cabarrus County in the Rocky River watershed.

In the mid-1980s, when Charlotte’s utility department forged agreements with the county’s smaller municipalities, the municipalities had the right to say no to sewer service if they didn’t want it in some areas. Davidson opted against sewer service for the rural area east of town, as a strategy to keep it rural. A Charlotte-Mecklenburg “2005 Plan,” adopted in 1985, even envisioned a state park in that northeast corner of Mecklenburg. But no state park was ever funded.

Davidson’s 1995 land use plan continued that keep-it-rural strategy, as did its 2000 Open Space Plan, which set a goal to preserve 50 percent of the rural area from development. But since then pressure to develop has been intense, and subdivisions have sprouted nearby, especially in Cabarrus County. In September town commissioners adopted a new Rural Area Plan covering 3,800 acres. The plan envisions more development and extending sewer lines into the rural area in three phases, with development scattered throughout, but it still aims to meet the goal of 50 percent of the total area remaining undeveloped.

MINT HILL AND GAR CREEK

For the unsewered areas in and near Mint Hill, Charlotte Water has proposed three pump stations to get the sewage over the ridge and into the drainage basin of the McAlpine Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant, Gullet says. One is imminent, another is envisioned within a five-year window and the third in a 10-year window. Farther east of Mint Hill sewer service is tough because the land is farther from any existing lines that lead to the Rocky River plant in Cabarrus County.

The final large area of unsewered land surrounds Gar Creek west of Huntersville. The area lies generally south of Hambright Road and north and west of Mount Holly-Huntersville Road. Much of the area is county-owned, purchased in an effort to protect Mountain Island Lake, a drinking water supply for almost 1 million residents. The area also includes the county’s 402-acre Gar Creek Nature Preserve, historic Hopewell Presbyterian Church on Beatties Ford Road, and Latta Plantation Nature Preserve.

This section of the county is in a critical watershed area where development is restricted in certain ways, although not prohibited. For instance, the proposed River District development west of the airport also includes critical watershed areas, but that does not preclude intense development as long as certain water protections are followed.

Countywide, it’s generally accepted policy today that almost all of Mecklenburg will eventually be developed, and any large preserved areas will be those the taxpayers have bought as parks and preserves or else land protected by private initiatives such as nonprofit land conservancies.

BACK ON THE RIVER

Over the years, Sue Friday and her husband have collected a jar full of pottery shards they found on their property, relics from residents of the area in decades past. Photo: Mary Newsom

Sue Friday has lived in the undeveloped area west of the airport for 37 years. Her 30 acres, not part of the huge River District development proposal, holds a Mid-Century Modern ranch house, a barn and a terraced back yard that slopes down to a pond. As the crow flies it’s 7 miles to the center of uptown Charlotte – closer to uptown than the Arboretum Shopping Center or the UNC Charlotte campus. She and her late husband bought their place in the 1970s, and in the intervening years she has been active as a voice for the area’s residents. Maybe not coincidentally, she was on the small committee that successfully campaigned in 1986 for the ill-fated farmland preservation bonds.

Friday spoke in favor of the River District proposal at the City Council’s public hearing, although she suggested that planning for the area should include the whole area, not just areas proposed for development. In an interview, she says that once Charlotte Premium Outlets shopping center went in at I-485 and Shopton Road, southeast of the proposed River District, “Most of us out here realized we were next.”

Her analysis is that lack of sewer service has been less of a deterrent to development there than the location of the airport and a long-standing (and inaccurate in her view) image of west Charlotte as a less desirable place to live.

But the fact that the once rural area is destined for change? Not an issue, she says. “If I wanted to live in the deep, deep woods I wouldn’t live in Mecklenburg County.”