An ‘economic halo’ for rural churches in North Carolina

In small towns across North Carolina, churches function as more than places of fellowship and gathering for people — they’re also de facto economic engines.

That’s one of the key findings of a new research report by the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, in partnership with The Duke Endowment and Partners for Sacred Places. “The Economic Halo Effect” examined a sample of 87 rural United Methodist Church congregations across the state and found they provide an average annual contribution to their local economies of over $735,000.

That impact stems both from direct spending on items such as salaries and building maintenance, and indirect sources such as providing community services and amenities like open space and recreational facilities.

“These are obviously places where the faith community gathers, worships and educates, but these are community-serving places as well,” said Bob Jaeger, president of Partners for Sacred Places. The group is a national, non-sectarian, nonprofit organization focused on building the capacity of congregations of historic sacred places to better serve their communities as anchor institutions.

Jaeger added: Rural churches are “not just worship places, but civic assets.”

This study examined United Methodist congregations eligible for Duke Endowment’s Rural Church program. It’s the first study of its kind to monetize the impact of church congregations in North Carolina’s rural areas. Partners for Sacred Places has previously studied urban congregations of various denominations in cities such as Philadelphia and Chicago.

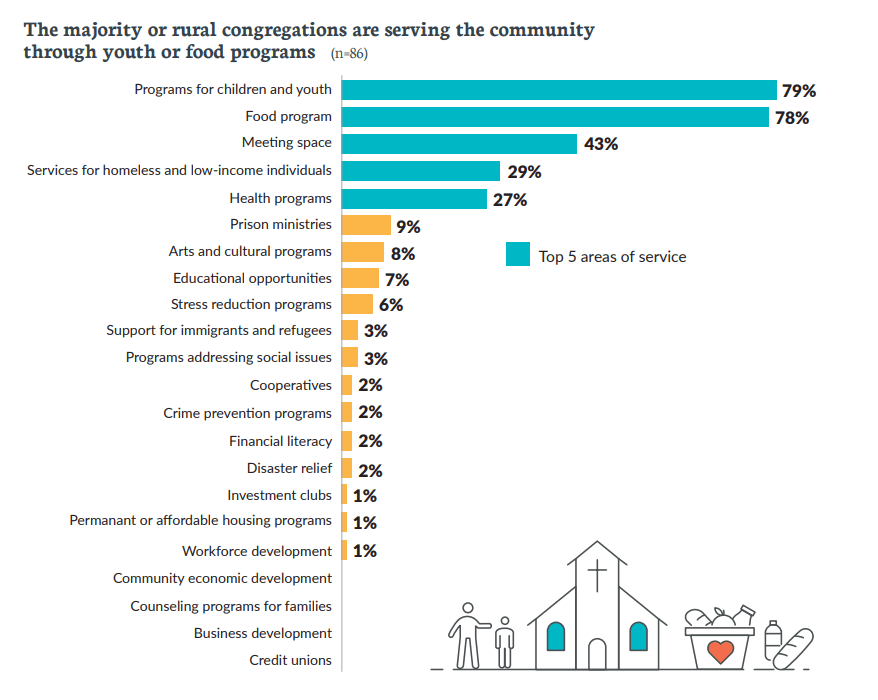

While the current study focused on a specific denomination, the researchers found that rural UMC congregations’ benefits aren’t limited to Methodists. In fact, 72% of people benefiting from rural UMC programs aren’t members of those congregations. And as North Carolina’s Urban and suburban counties grow while many rural counties shrink, organizations like UMCs provide an important bulwark for rural communities.

“To have a place to go for services that doesn’t require you to drive an hour is a huge benefit in many of these rural communities,” said Katie Zager, an Urban Institute research associate who co-authored the report.

Key findings include:

-

UMCs function as magnets in their communities, attracting an average of 195 visits per week to their locales. Only half of those are for worship activities — many people visiting UMCs are attending other events or programs.

-

Components of the UMCs’ average economic “halo effect” per congregation include direct spending ($186,095); the value of childcare programs ($165,208); the value of spending by visitors ($140,738); individual impact through outreach programs, counseling, workforce development and other programs ($116,764); community-serving programs such as food pantries ($109,275) and outdoor recreation and open space ($9,719).

If you add up the average economic impact for each of North Carolina’s 1,283 UMCs eligible for Duke Endowment’s Rural Church program, their impact totals $944 million annually.

-

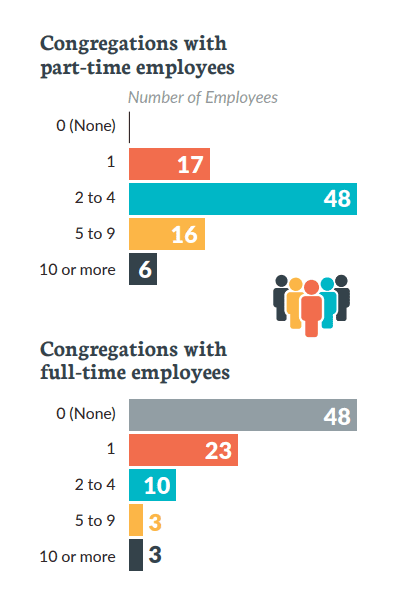

UMCs achieve this outsized impact despite having access to relatively small resources themselves. On average, churches had 1 or 2 full-time employees and 4 part-time employees; more than half of those churches studied are served by a part-time pastor. And 58% of those churches in the study had annual operating budgets of less than $100,000.

-

The services provided by UMCs can help offset some of the challenges rural communities face. For example, about a third of rural North Carolina children live in so-called child care “deserts,” without access to licensed child care, compared to 1 in 10 urban kids. Food programs help disadvantaged residents access nutritious food in rural parts of the state where public transportation is often unavailable and grocery stores are few and far between.

Rural churches are thus a vital part of any plan to preserve and reinvigorate rural communities.

“Rural UMCs are keenly aware of the assets and needs in their communities, and are working to provide a ‘safety net’ where government benefits do not suffice,” the study noted.

Putting numbers to impact

Rachel Hildebrandt, senior program manager at Partners for Sacred Places, said many people know that churches can play a vital role in serving communities. Spelling out the economic impact of that service, however, is important to illustrate just how vital they are to many rural areas.

“People kind of know it anecdotally,” she said, “But putting numbers to it is really important.”

In particular, rural UMCs excel at helping to address food insecurity and childcare access. That’s in part because they already offer food pantries, supplemental meals and food delivery services for local children. Many rural UMCs also have facilities that once housed larger Sunday school programs, which they offer at below-market rent to childcare and afterschool programs.

“Many have more space than they need or that they can use. There is a great opportunity to repurpose and reactivate these spaces in strategic and community-minded ways,” the study concludes.

“Many have more space than they need or that they can use. There is a great opportunity to repurpose and reactivate these spaces in strategic and community-minded ways,” the study concludes.

One significant limitation is the study’s focus on a single denomination, due to Duke Endowment’s historic ties to UMCs. The group of churches studied doesn’t reflect the full diversity and depth of religious communities and denominations in rural North Carolina. Additionally, the churches studied in this report are largely white, reflecting the demographics of their communities and congregations. Finally, some of the economic multipliers and other aspects of the study are specific to North Carolina, and caution should therefore be used in generalizing these findings to rural churches outside North Carolina.

As they help their communities remain vigorous even in the face of challenges, rural UMCs offer a blueprint for other communities of faith — and encouragement that small groups working with limited resources can make a big difference.

“Rural churches are great at doing a lot with a little,” said Hildebrandt. “Some of these congregations are punching way above their weight. If they closed, it would change the whole community in a negative way.”