Fighting over growth on Charlotte’s southern border

In the booming South Carolina communities nudging the southern edges of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County a civil war of sorts is erupting over how to manage growth.

It is not unusual for intense passions to shape local dialogue over what should and shouldn’t be built, and what it should look like. But in Lancaster and York counties, where mostly residential development has catapulted once rural areas into some of the fastest-growing in the Charlotte region, residents are clashing over a way of life.

[highlight]Booming York County growth provokes zoning, impact fee debates [/highlight]

This conflict is creating suspicion and resentment among neighbors. Elected officials are aggressively searching for ways to respond to an increasing chorus of complaints about traffic congestion, dense development and inadequate services. And developers are latching onto building opportunities as the demand for new apartments and single-family homes continues to surge in an improving economy.

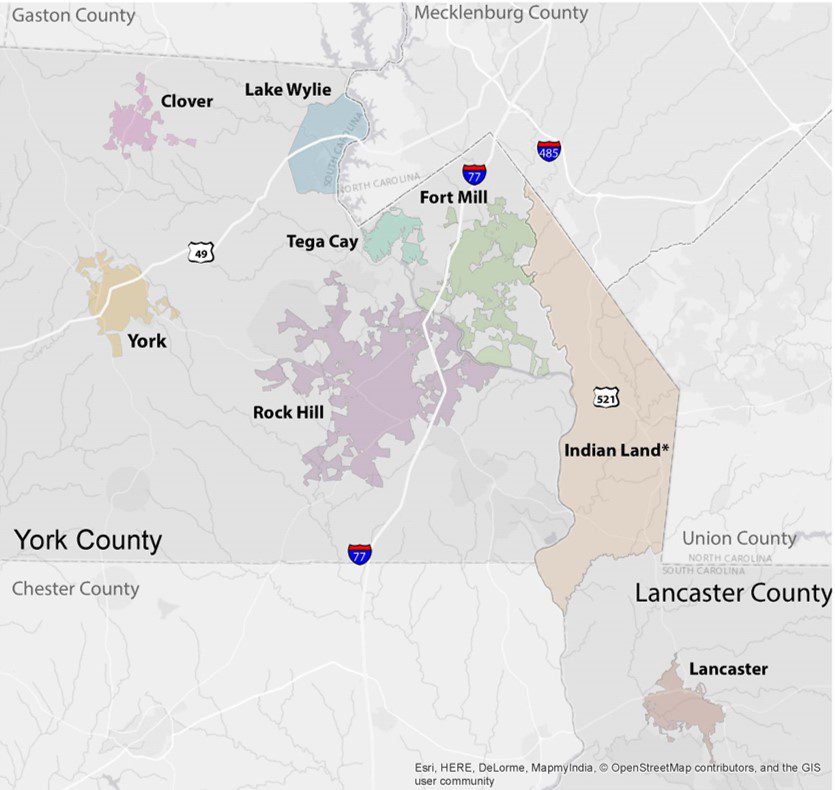

The rate of growth in the towns of Fort Mill and Tega Cay and the unincorporated areas of Lake Wylie in York County and Indian Land in Lancaster County outpace the growth in Charlotte, one of the fastest-growing cities in the country, according to the U.S. Census. As Charlotte grew 43 percent from 2000 to 2014, the population in Indian Land, just south of Charlotte’s affluent Ballantyne neighborhood, soared 209 percent, more than tripling in size. In Lake Wylie, which borders one of two man-made lakes in the Charlotte region, the rate of population growth 2000-2014 was even steeper, 215 percent. Tega Cay grew 103 percent.

In frustration, officials have enacted a moratorium on property rezonings for development in Indian Land. Other officials, facing intense lobbying pressures, have considered and rejected that idea. Planners, meanwhile, are developing guidelines for comprehensive growth plans and development ordinances to help improve the quality of development. Most of these proposed regulations will go to elected officials for final decisions in coming months.

Thousands of new residents in Indian Land seek lower housing prices, lower taxes and a less urban school system. Shown here is the Bridgemill neighborhood. Photo: Mae Israel

For the most part, new residents are attracted by lower taxes, lower housing prices and strong school systems. But local officials, in their effort to accommodate the population explosion, are hamstrung by South Carolina laws forbidding property tax increases that are above a small percentage. The state’s low gas tax means less spending to improve roads.

Click image for larger view of map

Moving to find more money, some communities have adopted impact fees, charges to developers to help pay for parks, fire stations and other services to meet the needs of new residents. Others are drafting proposals for them. Lancaster County even decided to get out of the road maintenance business in new subdivisions. Beginning this year, homeowner associations will have to pay to maintain their neighborhood streets, resulting in higher HOA fees.

“We’re trying to do our best to manage the growth,” says Lancaster County Council member Brian Carnes, who represents Indian Land. “It’s a desirable place to live, and a lot of people want to move there. We’re doing the best we can with the conditions and circumstances we have.”

One group of residents in Indian Land – an area that long ago was primarily populated by the Catawba and Waxhaw Native American tribes – is so fed up with what they consider inadequate services that they are collecting signatures to force a referendum on whether the area should incorporate to become a town. But another group has launched an effort to derail the plan. Both sides showed up at a precinct during the February Republican presidential primary. As supporters collected signatures, opponents walked up and began urging residents not to sign the petitions. There was no conflict, but to avoid any potential problems elections officials discouraged petition gathering at the Democratic primary a week later.

[highlight]“This is a ‘You’re not from here, we don’t want you here’ issue.” — Richard Dole, leading campaign to incorporate Indian Land [/highlight]

“We didn’t expect people trying to interrupt the petitioning process,” says Richard Dole, a leader of the Voters for a Town of Indian Land campaign and a five-year resident of the area. “This is a ‘You’re not from here, we don’t want you here’ issue. There is a difference of opinion, but we believe in settling things based on elections.”

In Indian Land, according to U.S. Census estimates, nearly 81 percent of residents in 2014 were born outside South Carolina, many of them likely bringing along differences in background, culture and expectations for quality of life to their new hometowns. According to data from Lancaster County, Indian Land has the highest median household income in the county – $57,989 in Indian Land in 2012, compared with $35,129 in the city of Lancaster in the more rural, southern part of the county.

The population of Lancaster, about 50 miles from Charlotte and the county seat, grew only 7.6 percent from 2000 to 2014. Only 22 percent of the city’s residents in 2014 were born outside of the state, compared with nearly 46 percent of Lancaster County’s 79,515 residents in 2014 who were born outside South Carolina.

Similarly, in neighboring York County large numbers of residents have moved from elsewhere. In 2014, nearly 87 percent of residents in the unincorporated Lake Wylie area were born outside the state; in the city of Tega Cay some 88 percent were born outside the state, and in the town of Fort Mill, 75 percent. More of the urbanizing areas closer to Charlotte are in York than Lancaster County, and nearly 63 percent of the York County population in 2014 was born outside South Carolina. (Census data don’t say how many of those born outside South Carolina were born in North Carolina.)

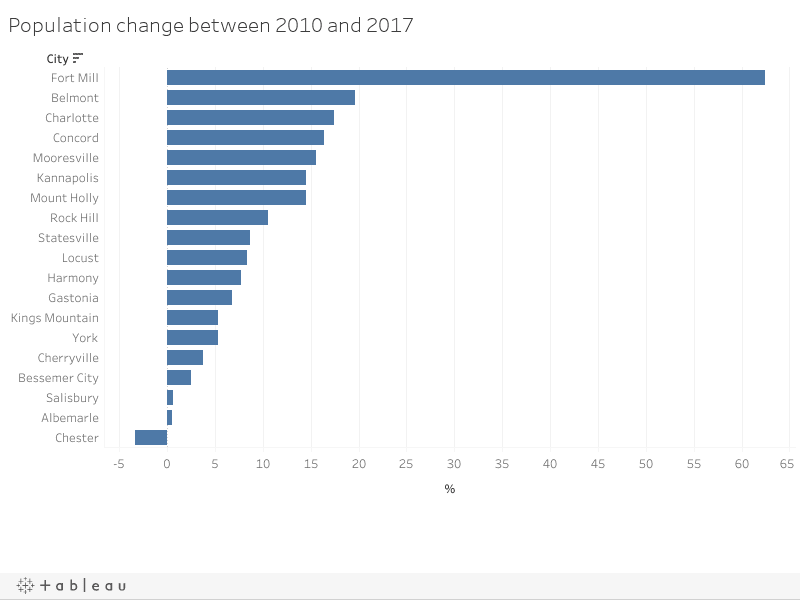

Graphic: Laura Simmons. Data: U.S. Census

“We’re starting to see some different ideas about the role of county services,” says Lancaster County Manager Steve Willis, describing some calls for service from Indian Land residents. “They expect people with animals to have licenses and to see somebody writing tickets if they don’t. We get calls about people shooting in backyards. People get angry about the county not plowing their subdivision streets. I’m not saying the expectations are unreasonable. Indian Land looks like a city, but is not a city. People expect city-type services.”

DISAGREEING OVER VALUE OF MUNICIPAL SERVICES

In the nearly 40-year-old Black Horse Run equestrian neighborhood in Indian Land, some homeowners still have backyard stables, and the area’s 11 miles of riding trails connect to each lot. This is where Pat Eudy raised her family, a retreat she has enjoyed for 30 years.

Indian Land – also known as the panhandle because of its tall, narrow shape – was “country” when she moved there from Monroe in neighboring Union County, N.C. The closest grocery store was about 20 miles north, across the state line in the Mecklenburg County town of Pineville. “It was peaceful and quiet,” she says.

Eudy, president of the Black Horse Run neighborhood association, supports growth in Indian Land but wants it to be better controlled and favors a proposed county unified development ordinance now under review. But she doesn’t want Indian Land to become a town.

A riding ring and horses in Black Horse Run neighborhood reflect Indian Land’s more rural past. Photo: Mae Israel

“Most of the grassroots people think we have what we need,” she says. “We don’t want higher taxes. I don’t know what services we would get that would be better. Most of us like it the way it is, except for the traffic.”

Richard Dole, leader of the effort to make Indian Land a town, disagrees. “Due to the rapid growth of the area, the management of all services is not being adequately performed by the county,” he says, pointing, for example, to an all-volunteer fire department instead of a fulltime paid staff.

Indian Land still has farmland and homes on large lots with grazing cows. “For Sale” signs are sprinkled along open land lining the roads between subdivisions, strip shopping centers and a Walmart. A movie theater is under construction. Since 2000, the area’s population has ballooned from 7,059 to an estimated 21,810 in 2014.

“People from more urban areas have moved here for quality of life, to be near grandkids and for low taxes, but they haven’t forgotten the luxuries of the major cities they left,” says Lancaster County Planning Director Penelope G. Karagounis. “Rural folks don’t want more development.”

Last June, the Lancaster County Council considered a moratorium to slow development in Indian Land, hoping to give the planning staff time to develop a countywide unified development ordinance to guide future construction. Work on the development ordinance follows the updating in 2014 of a comprehensive plan laying out general expectations for growth.

The council agreed to ban new rezonings but did not endorse halting construction by denying building permits. Developers can still move ahead on any of the thousands of houses previously approved for new subdivisions or commercial projects. The moratorium on rezonings is in effect until Sept. 8 but is likely to be extended until year’s end or until the Lancaster County Council adopts a unified development ordinance.

CODE CHANGE FOR LANCASTER COUNTY?

Nearly four years ago, the county council also enacted a nearly one-year ban on rezonings to allow for the development of a plan calling for tighter zoning restrictions in Indian Land. Officials did not approve the plan.

“We’re definitely changing the whole code,” says Karagounis of the new proposal. “We have created new zoning districts that are going to be flexible for developers to build mixed-use projects.” In recent months, public meetings have been held across the county as the ordinance takes shape. It’s been challenging, according to Karagounis, to find compromises among the differing opinions.

One touchy issue: mobile homes.

A planning staff analysis showed Lancaster County has more than 5,000 mobile homes with an average age of 25 years. But a proposal to only allow additional mobile homes no older than 25 years and to require conditional zoning to put them in residential areas drew concern from officials. They worried it was too restrictive, since mobile homes are an affordable housing option. A revised proposal maintains the age limit to help improve housing quality, but mobile homes will continue to be allowed, by right, in areas where zoning already permits them.

Lancaster County officials are also developing strategies to deal with the costs of growth.

Development along U.S. 521 has brought traffic to the once rural panhandle of Lancaster County. Photo: Mae Israel

A study is underway to determine impact fees on new development in Indian Land to pay for public safety, libraries and parks and recreation. Just across the line in York County, the Fort Mill School District already collects a $2,500 impact fee for residential construction.

While developers have successfully stalled most local government attempts at impact fees in North Carolina, where adoption of the fees requires state legislative approval, they are allowed under South Carolina law and an increasing number of fast-growing jurisdictions are moving to implement them. Fees went into effect at the beginning of this year in Fort Mill. Other impact fees are being collected in about 10 communities along the coast.

In South Carolina, local governments cannot look to property taxes as an option to pay for expanded services. For years, cities and counties have pushed legislators to lift a tax cap that restricts maximum tax increases to population growth and the consumer price index. Such increases, according to Willis, Lancaster’s county manager, do not provide enough money to start new services without significant cuts. The most that county taxes can increase for the 2016 fiscal year is 3.39 percent.

Officials also are considering a hospitality tax in the unincorporated areas, with most of the money potentially collected in Indian Land. Supporters of incorporating Indian Land say county officials are trying to lock in that additional revenue before Indian Land potentially becomes a municipality.

“Our goal is to get this referendum to give people the freedom to vote on their future,” says Dole, an engineer. A previous effort to create a town of Indian Land failed to bring the issue to a vote.

Meanwhile, in Van Wyck – a rural community in the southern end of the panhandle that’s been included in the proposed Indian Land town boundaries – residents want no part of it. In protest, they started their own petition drive and have submitted signatures to state officials seeking a referendum on making Van Wyck a town.

A huge sign in the community along U.S. 521 makes their message clear: “Van Wyck is not in Indian Land.”

Large lots and pastures along Marvin Road recall an earlier era of slower development. Photo: Mae Israel