Finding a lesson in city’s budget, streetcar impasse

How did this happen? How did a Charlotte City Council – with all 11 members willing to vote for a small property tax hike to pay for an ambitious, five-year plan of neighborhood improvements – wind up killing that five-year plan?

Plenty of armchair quarterbacking is going on now, divvying blame or credit (depending on one’s view), and puzzling out next steps.

• Did City Manager Curt Walton, told at the council’s retreat last winter to “be bold,” misread the message and offer a proposal that, at $926 million, was too bold?

|

Want to know more? For more information about the proposed $926 million capital improvement program, click here. For more news coverage of Monday’s council votes, click here. |

• Was the motion to kill the five-year capital improvement plan one of spite after a 6-5 vote for a CIP that didn’t include $119 million to expand the fledgling streetcar system? By Monday night, despite compromises on other items, the pro- and anti-streetcar blocs appeared unwilling to budge.

• Or was it, instead, a realization that even if the big spending plan passed via a mayoral veto –apparently votes were lacking to override Mayor Anthony Foxx’s veto – would the lack of robust council support undercut future bond votes needed to fund the program?

• And about that streetcar: The community is obviously divided. Neighborhood activists in East and West Charlotte adamantly favor it, but plenty of others complain about its cost and question whether it’s needed. Have supporters forgotten an important lesson from the unsuccessful 2007 kill-the-transit tax vote?

Whatever else Monday’s decision means, it means a long list of projects are, for now, unfunded. They include money to implement a series of area plans for Independence Boulevard, North Tryon Street, University Research Park and Dixie-Berryhill.

Also killed, for now:

• An idea to redevelop city-owned Bojangles Coliseum (the iconic 1950s-vintage coliseum on Independence Boulevard) and Ovens Auditorium. The proposal was to use public-private partnerships, buy some nearby problem properties and create an amateur sports complex.

• A proposal to spend $35 million to help the county expand its greenway system of walking and bicycle trails, connecting the UNC Charlotte area to Carolina Place in Pineville, via uptown and the SouthPark area.

• Six new police stations.

• A Comprehensive Neighborhood Improvement Program for five city areas: Central Avenue/Eastland/Albemarle Road, West Trade Street/Rozzelles Ferry Road, Whitehall, Prosperity Village and Sunset Road. The idea was to work holistically with city planning, transportation, neighborhood services and police, along with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, the county park and recreation department and private entities.

One explanation of the budget impasse lies in the dynamics of this particular collection of personalities – a situation typical for most government decisions. I think another likely factor is having four council newcomers. Another reason, though, lies in a relative lack of community and council debate on much of the massive, $926 million capital plan. To be sure, I didn’t attend all the budget meetings, but those who did say there was little debate until the June 11 meeting when the council failed to pass the budget.

As someone who pays closer attention than most I had heard, for example, that the CIP included $35 million for a Cross-Charlotte Multi-Use Trail. I didn’t know what it was until I burrowed through the city’s website. Ditto a $28 million proposal for an Applied Innovation Corridor from center city to UNC Charlotte. How many voters knew what was in, or out?

Further, much of the streetcar debate, at least among the public (since council members didn’t say much one way or the other until recent weeks) focused on whether it would be any faster than a city bus.

But – and what follows is a point made repeatedly in 1998, as advocates pushed for the countywide half-cent sales tax for transit – a streetcar is not only about transportation.

To judge it only by whether it would be speedier than driving misses the point. It’s about economic development. The streetcar system, when complete, would run down Beatties Ford Road, through uptown and out Central Avenue to what’s now the Eastland Mall carcass.

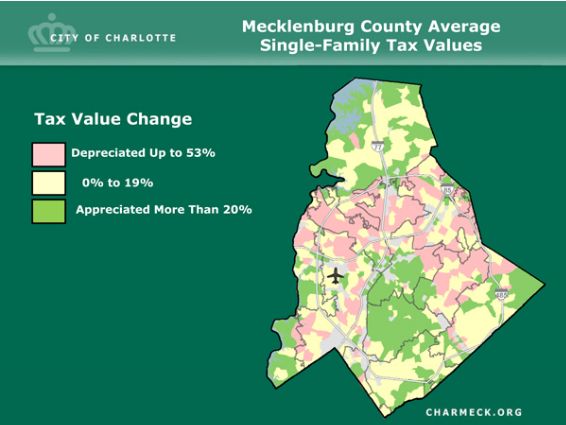

Lost amid remarks by some that a streetcar is just a toy, is this: Development reacts to streetcars differently from bus routes. If you’re a developer you know a bus line can be rerouted any time. Rails in the ground can’t. And luring development is important. The city’s tax base grew only about 7 percent from the previous 2003 property revaluation to 2011. A frighteningly high proportion of the city’s acreage is seeing declining, not rising, home property values. (See map at end.)

Further, cities across the country that built streetcars see them lure development. Seattle, Portland, Ore., and even Little Rock, Ark., offer proof. If streetcars are just silly aesthetics, then a whole lot of cities are being scammed, including Tampa, Dallas, Denver, Tucson and Philadelphia, all of which operate streetcars. Cities with streetcar lines under construction include Atlanta, Cincinnati and expansions in Seattle, Tucson, New Orleans and Portland, Ore. Cities with streetcars planned but not yet built (although in some cases already funded) include Oklahoma City, Phoenix, Sacramento, San Antonio and Fort Lauderdale.

I know all that because I did some research, not because I heard it from even council’s strongest streetcar supporters or the mayor. So I think it’s fair to conclude that arguments for expanding the streetcar weren’t being made with much visibility or with nearly the vigor of the arguments against raising taxes, or by those who think the project is silly.

The situation reminds me of something I learned from former Mayor Pat McCrory, a strong supporter of Charlotte’s efforts to build a public transportation system. My notes are lost to the vagaries of time, but I asked McCrory at some point near the end of his mayoral term in 2009 one of those cheesy journalist questions about lessons learned.

Here’s the gist of what he said: After the 1998 vote adopting the transit tax, he and others figured voters now understood a transit system was about development as well as transportation. The system shapes how the city and region grow. Advocates took the voters for granted, he said. By 2007 a kill-the-transit-tax movement emerged. Though it failed, McCrory said, you have to keep making the case. (Note: McCrory, a Republican running for governor, is no fan of the city’s streetcar project.)

Today’s streetcar supporters may want to consider that lesson, as they and other council members try to puzzle out what happens next.

Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, its staff or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.