Geographers, doctors and community members

The needs assessment was in response to Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s emergence as what Roberto Suro and Audrey Singer of the Pew Hispanic Center and Brookings Institution termed a “Hispanic Hypergrowth Metro.” Between 1990 and 2000 Mecklenburg’s Hispanic population – as captured by the census – grew by more than 38,000 persons (from about 7,000 to 45,000). In the last decade a similar pace of growth continued with Latinos now numbering over 111,000 representing 12.2 percent of the county’s total population. The large scale and seemingly abrupt arrival of Latino immigrants in Mecklenburg, coupled with the community’s relative inexperience welcoming foreign born and culturally distinct migrants, placed local leadership and service providers in the challenging position of having to meet the needs of these newcomers in a reactive rather than proactive way. The needs assessment, which was generously funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, played a critical role in identifying which public, private and non-profit programs and initiatives were in place and accessible to the county’s growing Latino population. It also illuminated areas of service that needed further expansion and enhancement.

Through surveys and telephone interviews, the Needs Assessment team asked Latinos about the kind of services and support structures they viewed as critical to helping immigrants in their community adjust and contribute to new lives in Charlotte. Among the top six identified, access to affordable health care was ranked third. This finding caught the attention of Dr. Michael Dulin a family physician with Carolinas Healthcare System – the region’s largest public health care provider. Dr. Dulin had recently taken up a new position at Eastland Family Medicine, one of CHS’s community based ambulatory clinics focused on providing primary care to the community’s underserved and impoverished residents. Important to this story is that the Eastland clinic was located in the heart of one of the primary Latino settlement areas as detailed in the Needs Assessment and yet Dr. Dulin was aware that very few of the clinic’s patients were members of this ethnic group. “Why was it,” he asked Heather Smith and Owen Furuseth (co-authors of the Needs Assessment), “that Latino patients are not coming to the Eastland Clinic when it is located in the heart of their neighborhood and focused on providing care for the indigent and underserved?” These questions were among the prompts that led to the development of a unique partnership between Dr. Dulin, Geographers Smith and Furuseth and leadership of the Latin American Coalition as each committed to working together to better understanding Latino and immigrant growth in the city and the challenges and opportunities that growth presented to healthcare providers and patients alike.

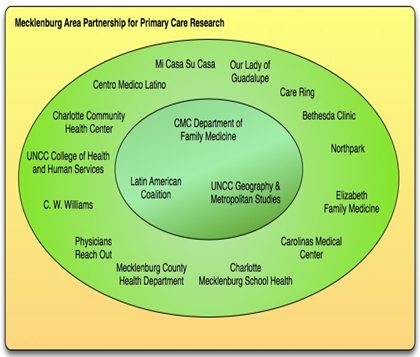

Established in 2005 under the leadership of Dr. Dulin, the Mecklenburg Area Partnership for Primary Care Research (MAPPR) is a Practice Based Research Network (PBRN) whose central goal is to bring about positive change by improving healthcare and quality of life for individuals and their communities. As Figure 1 details, the network comprises ambulatory care clinics located within the Carolinas HealthCare System, private/otherwise affiliated practices and community advocacy organizations. While today MAPPR is engaged in both clinical and community based work, in its earliest years its central focus was to better understand the barriers to primary care access for the Latino patients living near the Eastland clinic.

Figure 1. Mecklenburg Area Partnership for Primary Care Research

At the core of MAPPR’s Latino community-based projects are several questions:

- What are the major health issues facing both the Latino community members and their health providers?

- What are actual patterns of healthcare utilization?

- What are the barriers to appropriate and affordable healthcare for the Latino community in Mecklenburg County?

- How can barriers be overcome and to facilitate access to affordable and effective preventative health care services?

- How do we move from research to intervention that brings about positive change by improving healthcare and quality of life for individuals and their communities?

Our earliest research focused on identifying major health-related issues. With funding from the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Agency for Health Research and Quality and the Carolinas Healthcare System, MAPPR researchers conducted a series of key informant interviews and focus groups with both primary care providers and Latino community representatives to reveal clear and consistent consensus about the medically related issues that were (and continue to be) the most pressing. Given the rapid growth and maturation of the Latino immigrant stream to the region, the need for broader access to pre-natal care was cited as especially critical. Similarly, the high levels of stress and loneliness that often frame immigrant journeys and settlement processes translated into a clear need for expanded mental healthcare options. Substance abuse, sexually transmitted diseases and obesity were also viewed as responses to the challenges of immigrant adjustment and were highlighted by both community members and those in the medical field as growing concerns. In addition to these specific health conditions, interviews and focus groups also revealed concerns about barriers to access to appropriate primary and follow-up care and related overuse of Emergency Services, and lack of information within the community about the availability, location, appropriate usage and affordability of healthcare services.

These last two points provide the foundation for three ongoing research and outreach projects in which MAPPR partners are currently engaged. The first, funded through the Physician Faculty Scholars Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, is examining patterns of healthcare utilization; identifying barriers to healthcare access for Latino residents of Mecklenburg County; and developing interventions to improve primary care access. To date, this research has identified key barriers to primary care access as high cost, language and literacy and associated communication challenges, discrimination, lack of trust, cultural and spatial disconnects, and documentation status. In terms of interventions, this project is developing a comprehensive web-based community resource guide (ranging in topics from health, legal, government, education, etc.) and will train community members to promote the resource guide and be lay health /resource advisors in their communities.

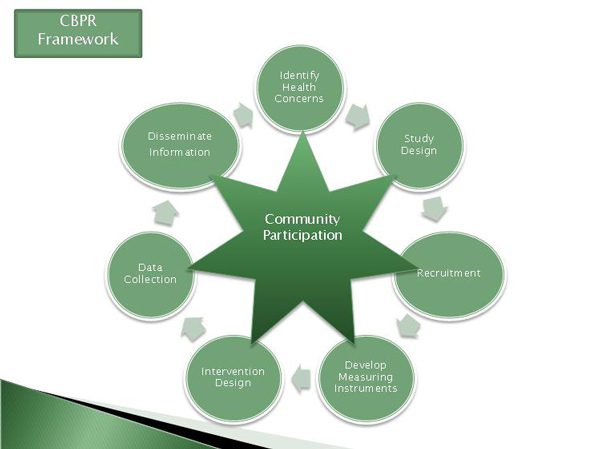

As is the case with all MAPPR community research, this project operates under the principles of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR). An increasingly popular way of doing research in frontline healthcare initiatives, CBPR “is scientific inquiry conducted in communities in which community members, persons affected by condition or issues under study and other key stakeholders in the community’s health has the opportunity to be full participants in each phase of the work: conception- design- conduct- analysis- interpretation- communication of results” (US Department of Health and Human Services, CPBR Scientific Interest Group). Figure 2 illustrates our operationalization of the CPBR approach and the central role of community partnership.

Figure 2: Community Based Participatory Research Framework

The second ongoing MAPPR project uses CBPR explicitly to build upon past research findings to design and evaluate an intervention that is designed to achieve the goals of improving health and quality of life for both the Latino and the broader Charlotte-Mecklenburg community. The project, funded by NIH, has leveraged the resources and expertise of our community partners to design, implement, and evaluate an intervention around a health condition chosen by the community. After a community forum identified obesity as the targeted health condition, MAPPR advanced its existing partnership with the Mecklenburg County Health Department to evaluate an already existing series of nutrition education and exercise classes for Latina women. Preliminary results indicate clear success not only on those measures related to obesity, but also evidence of social network building and improved mental health. This project is also developing a radionovela program profiling stories of health behavior and nutritional choices that will air on local Spanish language radio.

Our third and most recent project is also funded by the NIH and seeks to identify the social and spatial determinants of healthy communities. This project leverages the wealth of community data collected by the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute to identify neighborhoods that are at risk for poor health outcomes. Once these areas have been identified, the research team will partner with community members in these neighborhoods to develop interventions that improve access to preventative services with the aim of improving overall community health while decreasing the demands on hospitals and emergency services.

So, what has the MAPPR team learned since Drs. Dulin, Smith and Furuseth first discussed those questions about the barriers that prevented Latino patients from being able to see a primary care doctor?

First, just because a clinic is located in geographic proximity to a target population, doesn’t necessarily mean that patients will come through the doors. If a patient can’t read or speak English and the doctor can’t understand why the patient is there, or if they can’t get a ride to a clinic that provides culturally competent care, what choice does the patient have? Perhaps, wait until there is no option but to go to the Emergency Department? No option but to be hospitalized? Neither option is ideal. We need to understand that accessibility has to be measured in spatial, cultural, economic and social terms, and that accessible primary care is of benefit to both the patient and the broader community.

Second, we have also learned that barriers are not always obvious. Fear, loneliness and discrimination – all common to the immigrant experience – prevent patients from accessing needed healthcare. So too does a climate of receptivity that is hostile to newcomers. Some things are more difficult to change than others.

Third, we have learned the importance of being proactive rather than reactive. If, as service providers, we don’t look forward and learn more about the multiple cultural communities we serve, how can we ensure we are providing effective and efficient service? Proactive approaches provide information and support for patients to access appropriate care that ultimately translates into greater affordability and efficiency for all. Proactive approaches also help the community become better informed about the importance of embracing healthy lifestyles as a means to prevention.

Fourth, we have learned the value of information sharing. Broad dissemination of research findings, “best practice” ideas and successful outreach initiatives can minimize replication and maximize everyone’s ability to engage in strategic decision making. Sometimes information sharing can be challenging because to be effective it requires us to share both our successes and our failures. But what we have learned through our partnership is that knowing what doesn’t work is just as important and knowing what does work.

Finally, the most important lesson we have learned through MAPPR is the critical and enduring worth of community partnership. In our work, various members and representatives of the Latino community are essential partners in the design, operationalization and evaluation of our work. They are our patients, our research subjects, our colleagues, our partners, and our friends. Quite simply, MAPPR could not do its work without them.

Photograph by Heather Smith

Read the 2006 Mecklenburg County Latino Community Needs Assessment. (Available in English / En Espanol)

Heather Smith