Growth challenge dwarfs the streetcar spat

Since Charlotte Mayor Anthony Foxx gave his State of the City speech Monday, most of the publicity has focused on his remarks about the proposed streetcar, about a proposal in the legislature to remove Charlotte/Douglas International Airport from city control, and his comments about the Charlotte Chamber. Those are important issues. But another issue may well trump those, and it’s not getting much publicity:

The ways the City of Charlotte used to grow – in both size and tax revenue – are ending. “Growth by annexation is effectively over,” Foxx said.

For decades, a key tool Charlotte used to keep the population growing, property tax revenues healthy and tax increases in check was to continually annex newly built areas on the edge of the city. But the N.C. legislature in 2011 made involuntary annexation all but impossible for N.C. municipalities. And even without that change, Charlotte has almost filled the borders of what it could annex.

Couple the end of easy growth-by-annexation with a growing disconnect between, as Foxx put it, “vibrant areas and those in decline” – a situation not unique to Charlotte. What you get is a big problem: If large sections of Charlotte aren’t increasing in value, and the city can’t expand, that means property tax revenues won’t increase, either – unless the city keeps raising property taxes.

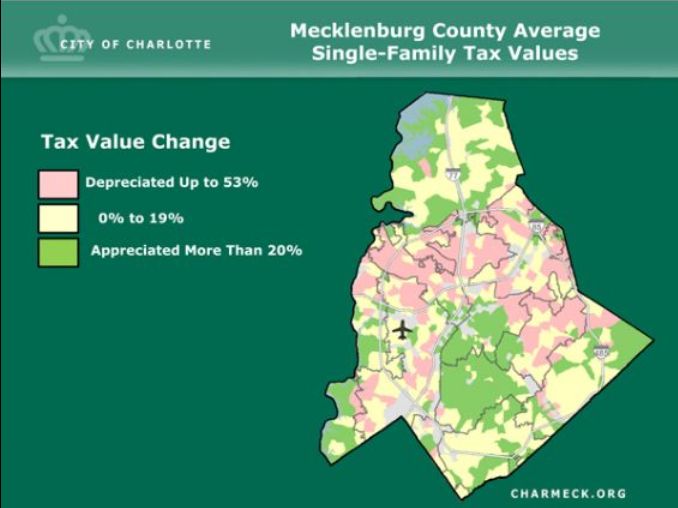

One of the scariest maps I’ve seen in recent months is this one, shown to Charlotte City Council members at last year’s budget retreat. (For a report on this year’s retreat, taking place today and Friday, see “What’s the City Council seeing, hearing at its retreat?”)

The illustration is blurry; it’s from a slide show. Even so, what it portends is easy to see. The large swaths of pink show where housing values sank by as much as 53 percent between the previous county property revaluation in 2003 and the most recent one in 2011. The pale yellow areas are where home values either stayed the same or went up by less than 20 percent. The green areas are where home property values rose by healthier amounts.

The conclusion: If you can’t count on healthy increases in property values – if too much of your city sees shrinking values – you’ll have to start raising city taxes by hefty sums to find the tax revenues to pay for police, firefighters, garbage collection, street repairs and other city (and county) services.

The City of Charlotte hasn’t raised its property taxes in almost seven years, Foxx noted. (If your city property tax bill rose, it was due to a higher property valuation.)

Foxx and other supporters of the proposed streetcar expansion say it would spark development in some parts of the city that need help – and could also help increase property values there.

Some background on the streetcar: It’s a form of light rail, although as proposed it wouldn’t run on an old railroad right-of-way as Charlotte’s Lynx does but in the street, akin to trams found in many European cities.

A 1.4-mile starter project is already funded with a federal grant and city money and will run from Presbyterian Hospital up Elizabeth Avenue and East Trade Street almost to Tryon Street.

The proposed (but not OK’d) $119 million expansion would run from The Square out West Trade Street to just past Johnson C. Smith University, and east from Presbyterian Hospital to near Central Avenue. Like other city transportation projects, the proposed expansion would be paid with city bonds, repaid from property tax revenues. Ultimately the proposed route goes west to beyond Interstate 85 and east to the defunct Eastland Mall.

Supporters point to the role streetcars have played in spurring intensified development in other U.S. cities, as well as to the continuing building boom in South End along the Lynx light rail.

But the streetcar has powerful political opponents, Gov. Pat McCrory among them. As Charlotte mayor, McCrory backed the streetcar as part of the Metropolitan Transit Commission’s transit plan in 2002 and 2006. But he opposed it when the city decided in 2009 to start building it without using MTC money, which comes from a half-cent sales tax in Mecklenburg County. McCrory has said he thinks the city shouldn’t build transit projects outside the MTC’s purview.

Streetcar or no, Charlotte still faces the overall situation of trying to grow from within, with no annexation. And redeveloping and adding density in an already-built city is much tougher than building on a patch of woods or cow pasture outside town. “Density” may be beloved by urban designers, but to many people it sounds like a high-rise housing project with roaches and broken elevators. And faced with multistory buildings proposed next door, even the fairest-minded homeowners can transform into NIMBYs faster than a werewolf under a full moon.

So, yes, the streetcar might well be a fabulous tool for helping parts of the city revive. But it has vigorous political opposition and, so far, no majority of support on the City Council.

Is it really the only tool available for revitalization? Foxx and the streetcar supporters who argue it’s needed for revitalization might want to have Plans B and C in mind. Because the big problem – how the city will grow and stay healthy – is likely to be with us for decades.

Opinions in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.