The haunted history of reclaiming a floodplain

Chantilly Ecological Sanctuary, informally known as Chantilly Eco-Park, is an oasis in East Charlotte, a part of the county underserved by green space. Hugging a section of Briar Creek, its roughly 24 acres support lush wetlands, regenerating forest and grasslands riddled with butterfly weed. This outstanding wildlife habitat – over 160 species of birds have been documented here – is hemmed in by apartment buildings, a vast parking lot and a busy stretch of Monroe Road. Watching a green heron skulk among the blue-flag iris and pickerel weed while a red-winged blackbird belts out its exuberant song from its perch on a stalk of native hibiscus, it’s hard to believe this park itself was also once covered in concrete and asphalt.

Back in the 1960s, when there were no restrictions on building in the floodplain, apartments were constructed along the banks of Briar Creek. Over the years, as more development occurred in the watershed and storms became more intense due to climate change, the usually placid creek began to flood the dwellings more frequently and more severely. This no doubt made the apartments less appealing, so the rents were more affordable for people with low incomes. As a result, some of our most vulnerable citizens moved into some of our most vulnerable housing.

In the 1990s, the buildings started flooding on a regular basis, causing millions of dollars of damage and endangering the lives of residents and emergency responders alike. The city of Charlotte eventually sought funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to buy out the Cavalier Apartments on the northwest side of the creek and later a portion of the Doral Apartments along the southeast bank. The buildings were demolished, and the cleared land underwent a radical transformation, returning to a highly engineered version of its former self.

The tenants who were forced to leave received some amount of relocation assistance, but even in the best of circumstances it’s challenging for people with limited resources to pack up and start over elsewhere. As I walked through the inspiring natural areas at the Chantilly Eco-Park, I wondered what had happened to all those people.

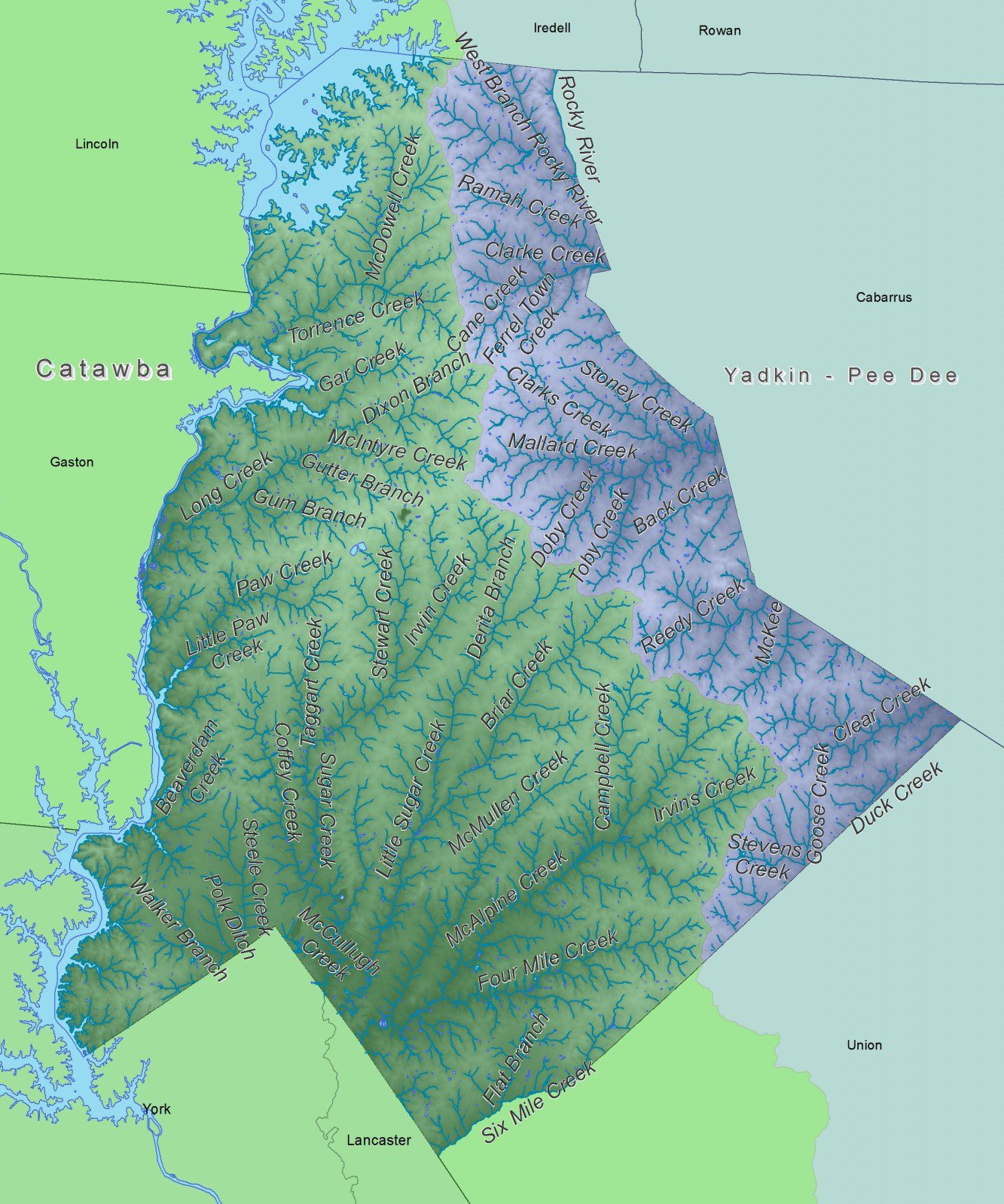

The term “climate refugees” – people displaced from their homes due to the effects of climate change – might conjure images of tiny islands in the Pacific or coastal areas of countries like Bangladesh. In reality, displacement is also happening to people in our own backyards. Citizens of Charlotte, an affluent city hundreds of miles from the coast, in the most affluent nation on earth, are also being driven from their homes due to climate change. As a map at the Climates of Inequality exhibit at the Levine Museum of the New South illustrates, Charlotte is a city of creeks. Neighborhoods throughout the county could face similar risks in the future.

Map by Garrett Nelson, KeepingWatch.org

Charlotte is by no means alone in struggling with the tragic consequences of climate change. In The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration, Jack Bittle explores the impacts on people in communities across the nation – hurricanes in Houston, wildfires in Santa Rosa, drought in Phoenix and sea-level rise in Norfolk.

He highlights the experiences of two locations in eastern North Carolina. Lincoln City, a neighborhood in a bend of the Neuse River in Kinston, and nearby Princeville, a town on the banks of the Tar River, were both ravaged by Hurricanes Fran in 1996 and Floyd in 1999. Both also have proud and storied histories as communities built by and for African Americans. It’s a hard thing to walk away from ties like that. After much deliberation, many residents of Lincoln City accepted relocation buyouts. While Princeville’s town council chose not to go that route, some of its residents ended up leaving anyway. Bittle’s poignant reporting shows that any sort of “diaspora” can undermine a neighborhood and sense of community. He notes that climate change actually wasn’t the primary culprit. Instead, it was “the silent hierarchy that divides land along the lines of race and class.”

Chantilly Eco-Park is allowing this stretch of Briar Creek to function as it should have all along. The permeable land is slowing and absorbing flood waters that nourish the native vegetation adapted to these conditions. The park protects people and structures in the immediate vicinity and also those far downstream, while also benefiting an array of wildlife. The park is a glorious example of habitat restoration, but there’s something haunting about the site. It’s an acknowledgement of our past mistakes, our subjugation of people and nature. It stands as a monument to our complicated history and a reminder of the lessons we should glean from it.

For more information on the floodplain restoration project, go to Earley-From-Buyout-to-Restoration.pdf (ncsu.edu).

Climates of Inequality exhibit is on view at the Levine Museum of the New South through September 7, 2023. Climates of Inequality | Levine Museum of the New SouthClimates of Inequality | Levine Museum of the New South

The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute co-led a project examining wildlife habitat in the urban ecosystem. Visit KeepingWatch.org and click on “Explore Creeks” for stories, videos, maps and other information about Mecklenburg County’s creeks.