Historical Overview Part 2: Post-Civil War, the region becomes an industrial system

The lack of industry and infrastructure at the start of the Civil War meant that our region largely escaped damage during the conflict.

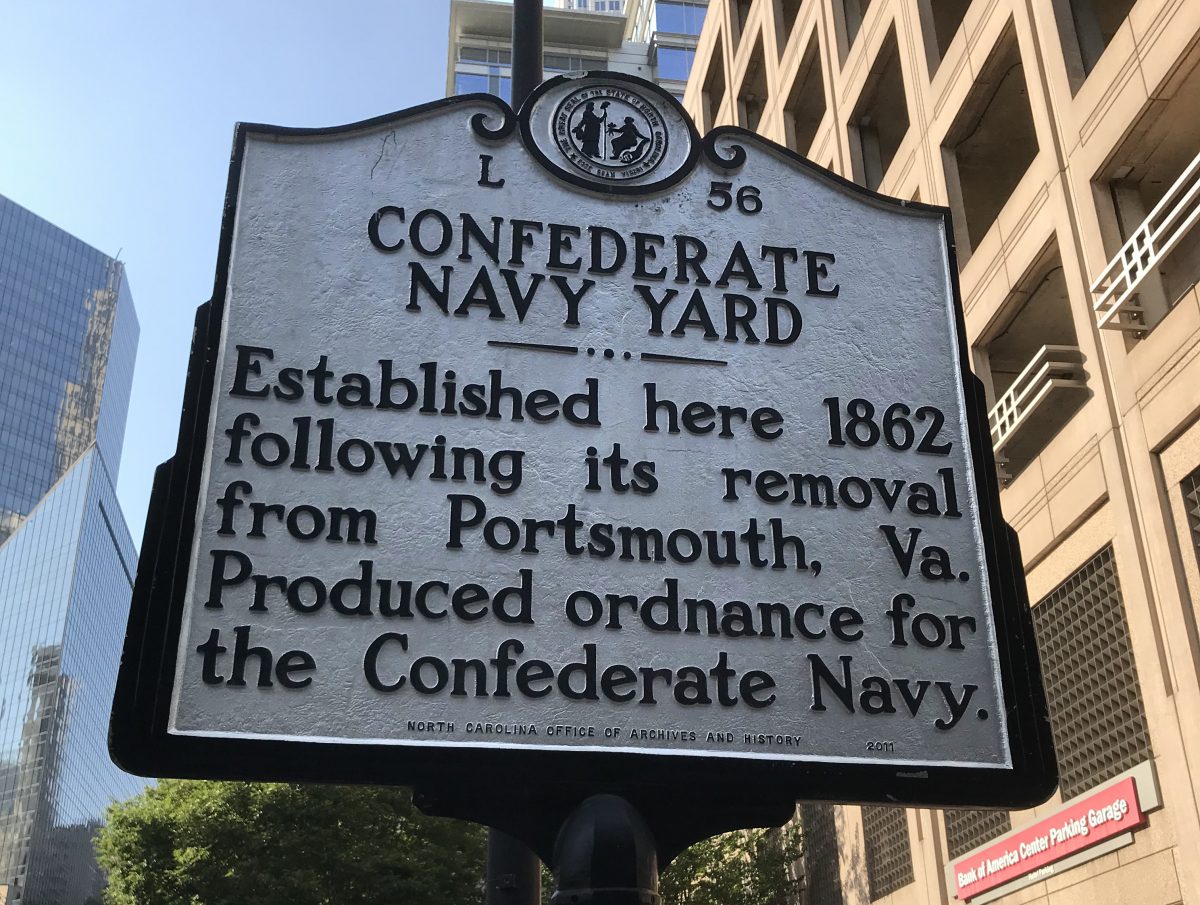

This local calm revealed the degree to which our region was isolated from the rest of the nation — an isolation that became an advantage when the Confederate government chose to relocate its Navy Yard from Portsmouth, Virginia to the relative safety of ‘backcountry’ Charlotte.

Figure 4: Historical marker discussing the Charlotte Navy Yard – the seed of our industrial specialization – on Tryon Street. Photo: Bill Graves

The Yard produced the majority of the Confederate Navy’s metal and munitions (needless to say, no ships were built here). The Navy Yard left behind a skilled industrial workforce, a first for the region, that could seed the early stages of the area’s textile boom.

The ironically located inland Navy Yard provided us with an industrial workforce, but making them productive in private industry required a way to get their products to markets. The region’s first railroad, the Charlotte and South Carolina, connected Charlotte to Columbia, and on to the port of Charleston. It was completed in 1852 with the purpose of extracting resources (predominantly cotton) from the isolated Western Piedmont.

Now, the Southern portion of Charlotte’s Blue Line light rail travels along this route within Charlotte. The original route’s Northern terminus was selected thanks to proactive and collective capital raising by Charlotte’s farmers, lawyers and merchants, all of whom rightly speculated that land values would increase thanks to reductions in the cost of transporting crops (see Hanchett 1998 for a larger discussion).

The railroad did indeed increase regional prosperity, doubly so when it encouraged the state-owned North Carolina Railroad (NCRR) to make its western terminus the Charlotte rail junction (the only location in Western North Carolina where this was possible at the time). The arrival of the NCRR made Charlotte the most accessible location in the Piedmont, providing local farmers huge advantages over those in more distant locations. For the first time, the region was becoming part of the broader national economy.

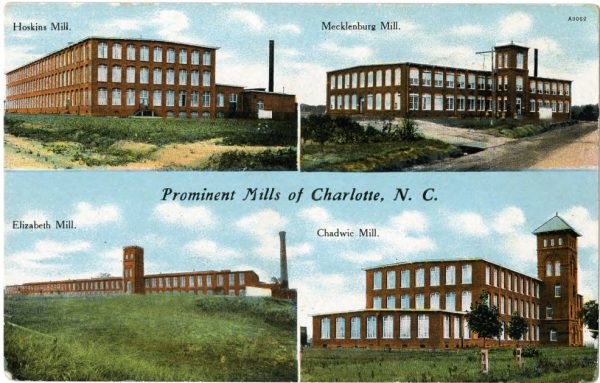

As railroad construction increased after the Civil War, the textile industry followed. The combination of plentiful, inexpensive cotton, railroads, and an ample labor supply off the farms encouraged Northeastern textile mill owners to move South. Mills sprouted quickly in the region, increasing from just 25 in 1840 to more than 200 by 1900. By 1923, North Carolina had more textile mills than any state other than Massachusetts (Dowd Hall et. al. 1987). Gaston and Cabarrus counties experienced the most dramatic industrial growth during this era.

| The Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection A special project from the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute |

|---|

| Read about the project here |

| Historical Overview Part 1: Early development of a connected region |

| Introduction: Strengthening ties to revitalize communities |

| Trails, roads, rails and sky: The changing physical connections that knit our region together |

A similar transformation occurred in the Northern portion of the region. The hardwood trees on the Blue Ridge could be cut, milled and sent by rail to furniture factories in Lenoir, Hickory and Lexington. This production would have been impossible without the railroads providing low-cost connections to distant markets. The region’s natural resources had little value without these linkages.

Since nearly all of the new railroads in the region sought to connect to Charlotte’s junction, the city quickly developed into a distribution hub. Charlotte was the central location where raw materials were gathered, products distributed, and machinery, parts, and expertise were all available. Mill owners preferred isolated locations for their factories — primarily as a means of keeping labor costs low — and the railroads made that possible (Figure 5).

Towns such as Cliffside, Cooleemee and Winnsboro became flourishing industrial towns virtually overnight. The rural factories relied on Charlotte for distribution, purchasing and financial services. Workers used the railroads to connect them to the shopping and entertainment options not available in their villages.

This economic system was symbiotic; Charlotte’s economy depended on the rural mills to fuel its growing distribution and financial industries while the small-town workers saw the city as their best option for consumption of goods and services. This interdependence fueled a new prosperity throughout the region in the early 20th century. Charlotte grew rapidly, but the small towns in the region were truly transformed from their agricultural pasts. The Western Piedmont was one of the few places in the world where rural industry was efficient and competitive.

Figure 5: The Charlotte Region, its railroads and mill villages in 1900. Modified from Lemert (1933) by the UNC Charlotte Department of Geography and Earth Sciences Cartography Lab.

Unfortunately, geography constrained our growth in comparison to other urban regions. The Piedmont’s location at the foot of the Blue Ridge meant direct connections to points west were impossible; North Carolina’s mountains were too tall and too wide to traverse by rail. Charlotte’s newfound centrality extended for less than 100 miles – any products headed west had to go through Atlanta and anything going North was more cheaply sent from Greensboro or Richmond.

But to the East, unrelated events were about to dramatically improve our region’s fortunes. James B. Duke had become one of the world’s richest individuals by licensing the ability to mechanically roll cigarettes from local tobacco in Durham. This license, along with his marketing skills, created the massively successful American Tobacco Company. His success in packaged tobacco was massive but short lived: American Tobacco was found to be in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act and the company was broken up by regulators. Duke turned his attention, as well as his fortune, over to his ambition of industrializing the remainder of the Piedmont.

The Catawba River basin was well suited to the generation of hydroelectric power and Duke was well aware of the efficiency benefits of using electricity (as opposed to steam or water power) in manufacturing. Duke created the Southern Power System (later to be known as Duke Power) in 1905 with the intention of providing low-cost electric service to the Carolinas in the hope of attracting additional industry.

The genius of Duke’s plan was to use the power generated in local factories, since electrical transmission technology of the time prevented the Catawba dams from generating power for distant places. Great Falls, South Carolina was selected as the first dam site and transmission lines were quickly built to deliver power to Charlotte, Shelby, and Gastonia, and later to upstate South Carolina.

By 1914, Duke’s electrical transmission system was said to be “by far the most extensive interconnected transmission system in the world” (Durden 2003, 126). This widely distributed and inexpensive hydro-power encouraged new manufacturers to locate in rural sites around the Piedmont. Duke’s desire to keep electrical prices low encouraged the rapid adoption of the new technology and provided local producers with significant cost advantages over factories in most other regions of the country. The Southern Power System made the region one of the preeminent industrial districts in the South in the early 20th century.

The population change animation in Figure 3 illustrates many of these trends. Population throughout the region, but particularly in North Carolina, began to increase steadily after 1880. South Carolina’s counties became relatively smaller due to the impact of Reconstruction on plantation economies. The impact of railroad construction and its associated industrialization is also evident beginning in 1880, with York, Mecklenburg, Catawba, Cabarrus and Rowan counties seeing the bulk of the railroad-related growth. Between 1900 and 1910 the arrival of rural industry (thanks largely to Duke’s power network) can be seen with dramatic population growth in Cleveland, Gaston and Iredell counties.

Much of the region’s growth through 1970 was a product of factories and mills in rural areas, as well as Charlotte’s transformation to post-industrial activities, which began to trigger suburban growth in surrounding counties.