Historical Overview Part 3: The rise of banking builds a globally connected region

While Duke was building the world’s largest electrical network in the Western Piedmont, some Charlotte mill owners recognized that more money could be made loaning money to aspiring industrialists than making cloth themselves.

This realization led to the creation of Commercial National Bank in 1874 (a forerunner of Bank of America) and Union National Bank in 1908 (a forerunner of Wachovia/Wells Fargo). These banks, and several others, funded much of the region’s early 20th century industrial growth. But banks, by themselves, were not sufficient to transform Charlotte into the second largest banking center in the country.

Thoughtful and light regulation by the state of North Carolina helped nurture these banks into national giants. This regulatory strategy was partially a result of the state’s historic poverty – North Carolina was simply too poor to place the same limits on bank expansion as were found in other states following the Great Depression. Banking was also a critical element fueling the region’s growth. Banking not only provided capital to local industry, but it also served as our first example of local knowledge industries successfully competing in national markets.

Charlotte’s skyline, at a time when the Commercial Bank building (white, background) was one of the tallest structures. Source: Atkins Library

Like textiles, banking spilled over into institutions which enabled the region to evolve into the post-industrial age. One of those institutions was the Charlotte Douglas International Airport. Charlotte’s bankers were frequent business flyers and their spending justified the creation of a hub for Piedmont Airlines, USAir and, eventually, American Airlines. Hub status has proven far more important than mere bragging rights for the Carolinas.

The availability of direct flights to nearly 200 destinations is far in excess of what would normally be found in a region of our size. These flights in turn make our region attractive to a wide variety of national and international firms such as Sealed Air, Honeywell and Dimensional Fund Advisors that value our accessibility to the wider world. These regional advantages have produced a growth rate in our region’s 32 counties that is nearly double the US population change since 1970. Mecklenburg’s population growth since the 1970s (Figure 3) was largely a product of this economic transition.

Deindustrialization

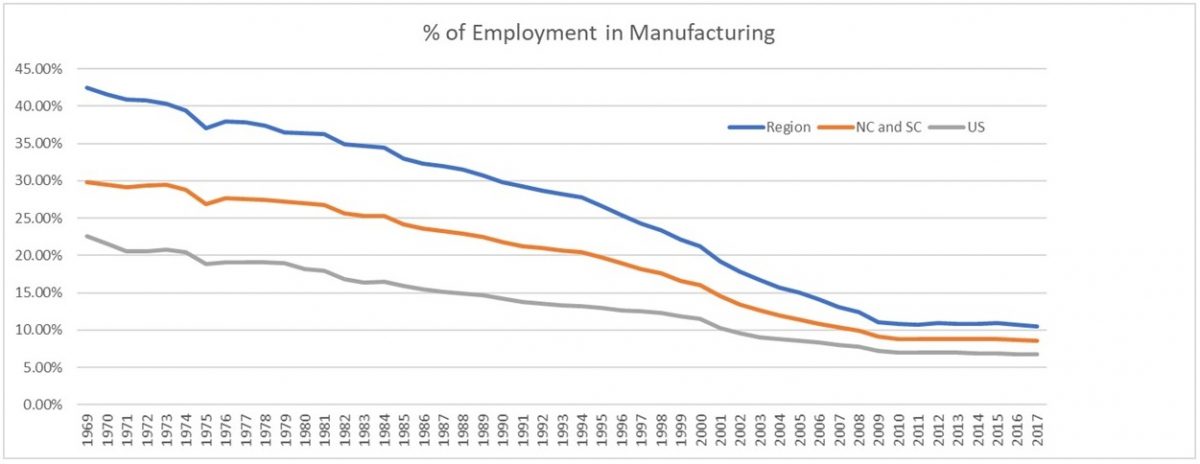

Railroads, banking, an eager labor force and James B. Duke’s fortune combined to make our region one of the most manufacturing-intensive places in the United States. Unfortunately, our region’s rural manufacturing firms began to shut down just as Charlotte began transitioning to the post-industrial age. Factory employment now accounts for just 11 percent of the region’s total workforce after peaking at 42 percent in 1969 (10 years after US manufacturing employment peaked).

While local manufacturing employment is a fraction of what it was 50 years ago, it is still significantly higher than the 7 percent figure for the US. The loss of manufacturing in our area can be blamed on a myriad of causes: foreign trade, low rates of reinvestment, and industry maturation (among others), but the job losses, in aggregate, can’t be attributed to a single event.

The loss of factory employment impacted the small-town portions of our region in particular. Mills and manufacturing were frequently the only source of employment in these places. Any large industry that now considers these locations (such as server farms) only employs a handful of workers in comparison to the giant mills and factories. The loss of manufacturing required residents to either relocate to larger places, adapt to extensive commutes if they wanted to remain in their homes, or drop out of the labor force.

Mill management was also involved in community development, for the simple fact that owners had a vested interest in local government and nonprofit health systems. The loss of the local mill thus cost communities much of their human and financial capital, in addition to the direct impacts on employment and local income. These changes resulted in a dramatic hollowing out of many local communities as the residents who remained in place had little time or energy available for community customs, local entrepreneurship or leadership.

Even the industrial structures themselves disappeared in many cases – a visitor to a community such as Cooleemee or Cliffside today would struggle to discern any remaining sign of a mill or railroad. However, many of the mills closer to Charlotte, where land prices and demand were higher, have been preserved and repurposed for housing, entertainment venues, breweries and offices.

The loss of rural factory jobs combined with the rise of knowledge industries in Charlotte created a region that is more dependent on the city of Charlotte for employment than ever before. Younger people possessing the necessary skills often relocate to Charlotte to be closer to jobs. Those left behind have seen online retail and entertainment options emerge that have allowed them to reduce their connections to the city and also eliminate local service industry jobs.

Loray Mill in Gastonia. Part of the main mill building has been redeveloped into upscale apartments. Photo: Nancy Pierce.

While new forms of production have increased wages in Charlotte and increased convenience in surrounding counties, the interdependence of past eras has been weakened and inequality within our region has increased to levels never before seen. The loss of connections within our region has given many of our residents the sense that our communities are now evolving alone, rather than as a group.

Population in the counties outside Charlotte’s suburban belt (Figure 3) has been largely flat since the 1980s. Unlike in the Midwest, deindustrialization in our region did not trigger widespread out-migration. Most residents remained in their communities even after factories closed. Since 1990, most of the region’s growth has been driven by Charlotte’s suburban expansion.

| The Carolinas Urban-Rural Connection A special project from the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute |

|---|

| Read about the project here |

| Introduction: Strengthening ties to revitalize communities |

| Historical Overview Part 1: The early development of a connected region |

| Historical Overview Part 2: Post-Civil War, the region becomes an industrial system |

| Trails, roads, rails and sky: The changing physical connections that knit our region together |

The Charlotte region has changed remarkably over the past three centuries. Our 32 counties were among the nation’s most isolated in the Antebellum era. The intentional efforts of our leaders (Charlotte’s planters raising money for the railroad or James Duke building his electrical system) enabled our transformation into an industrial powerhouse. This industrial age created small-town and rural growth in our region which was nearly unheard of in the remainder of the country.

Unfortunately, this shared prosperity came to an end in the 1980s. The factories powering this rural prosperity aged into obsolescence. Some firms have stepped in to fill at least a part of the void: Apple in Catawba, Facebook in Rutherford and Google in Caldwell have come to take advantage of the same power grid which attracted the mills they replaced. Sadly, there is no sign that the new industries will employ more than a fraction of the workforce.

Unlike most other post-industrial regions, however, our core continues to flourish. Charlotte’s current success is very much a result of our region’s history of isolation and rural industry and its continued health is dependent on the cooperation of the surrounding region. History shows us that spreading this prosperity to the remainder of our region will depend on finding new ways to connect our communities.