Hitting the bottle: Do drink sales shape where growth goes?

For years subdivisions have been filling acres of farmland in Union County. Yet developers there are looking longingly at missed opportunities for restaurants, grocery stores and convenience stores. Unincorporated Union County is dry. That means no public sale of beer or wine. No liquor stores. No liquor-by-the-drink.

“I know there is interest in an upscale restaurant (in some areas) but they’re not going to build as long as they don’t have mixed drink sales in the community,” says Richard Helms, chairman of the Union County Board of Commissioners. “Drug stores, convenience stores and restaurants contribute to the economic growth of the county. They bring in jobs.”

It’s an axiom of planning textbooks that sewer lines and roads shape growth. “Growth follows the pipe,” is one expression. But in North Carolina, where alcohol sales traditionally were viewed with deep suspicion by conservative Christians (and discouraged by  bootleggers seeking business), it appears growth also may follow the bottle.

bootleggers seeking business), it appears growth also may follow the bottle.

Local government officials grappling with tight budgets, raising taxes and demand for services are considering the potential of alcohol sales to bring in more revenue. In places where no alcohol sales are allowed, residents who want a glass of wine or a beer with dinner at a restaurant, or who want to pick some up at the grocery store, have to drive somewhere else. And developers of shopping centers, grocery stores and restaurants tend to look elsewhere.

“I don’t know of any supermarket in Gaston County that is located outside of a municipality,” says planning consultant Jack Kiser, a retired planning director for Gastonia. Gaston County is dry; county voters in 1948 rejected a proposal for alcohol sales. In 1985, Gastonia was the first municipality in that county to adopt liquor-by-the-drink. Over the past decade residents of 11 of the county’s 15 municipalities authorized it for their communities.

Even though a mix of factors contributes to commercial growth, planners and others say alcohol sales are a primary catalyst for attracting restaurants and stores, many of which depend heavily on alcohol sales to make a profit.

“If Charlotte didn’t have liquor-by-the-drink, they wouldn’t have the Carolina Panthers and all the professional sports,” says Mike Herring, recently retired administrator of the North Carolina Alcohol Beverage Control Commission, who during more than 33 years with the agency watched mixed-drink sales spread across the state. Mecklenburg voters were the first in the state to approve liquor-by-the-drink in 1978, decades after supporting the sale of beer and wine and ABC stores.

In Union County, Richard Helms has watched the growth patterns for commercial development that favor locations where alcohol sales are legal. He says he plans to ask Union County commissioners later this year to consider putting a referendum on the 2016 ballot to approve selling beer, wine and mixed drinks in the county.

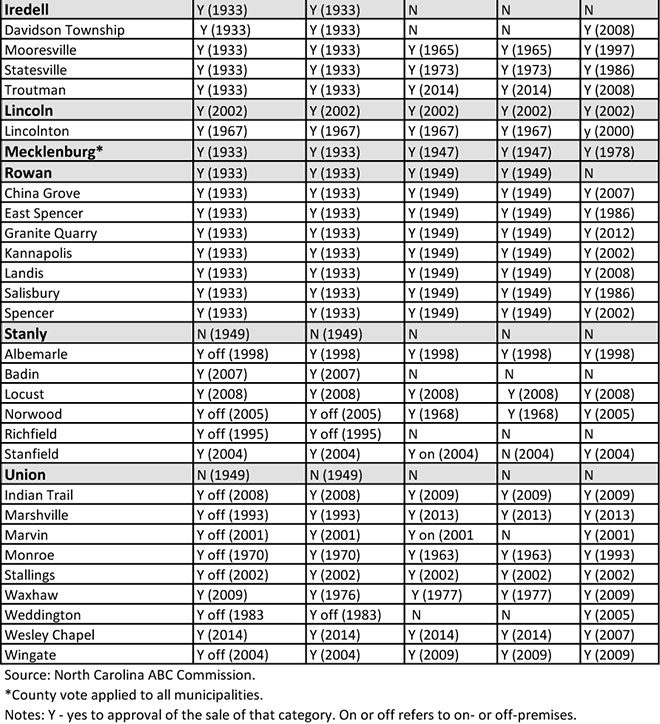

Union County residents voted in countywide referendums 1949 and later in 1981 to prohibit alcohol sales. Since then, nine of the county’s 14 municipalities have held separate votes in which residents approved the sale of mixed drinks, beer and wine.

“It’s an issue that we need to address,” says Helms. “It has a definite economic impact on the county.”

In North Carolina, as newcomers have flooded communities in recent years, elected officials have put a steady stream of alcohol referendums on the ballot. They seek voter approval by raising the possibility that allowing liquor-by-the-drink could lure more commercial development while providing property tax money to help pay for schools and other services.

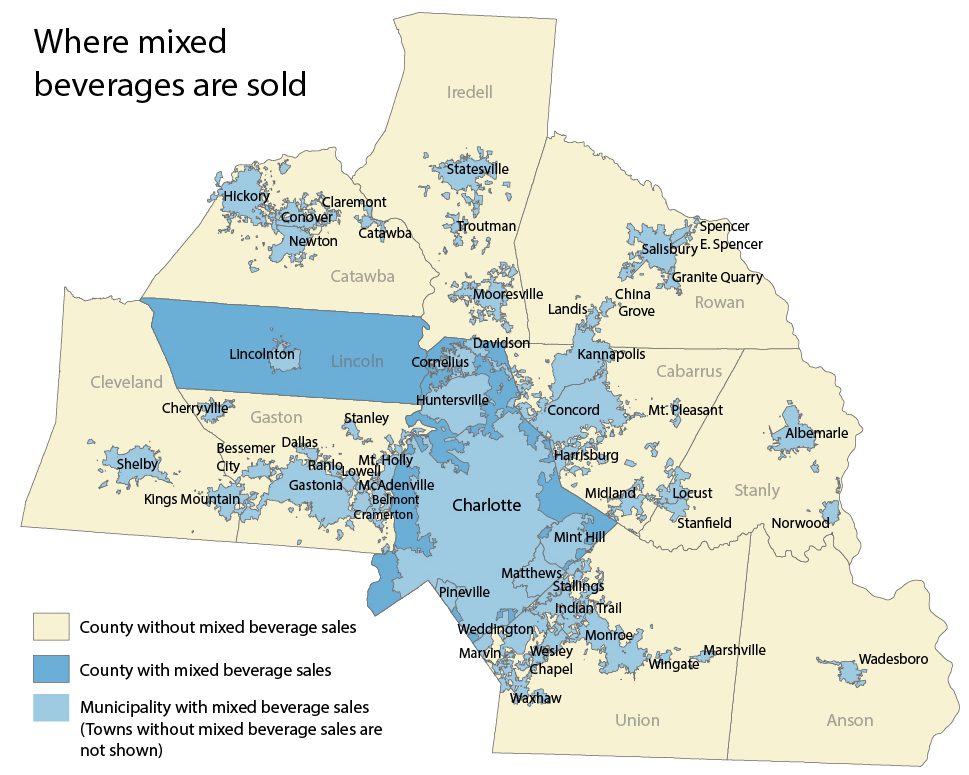

Among North Carolina’s 100 counties only 30, including most of the large urban areas, have countywide alcohol and mixed drink sales. In the Charlotte region, only Mecklenburg and Lincoln have countywide sales. Catawba County allows all alcohol sales except mixed-drinks. But during the past 15 years, in each of the region’s 10 counties outside Mecklenburg, at least one municipality has put some form of alcohol sales on the ballot.

In Gaston’s town of Mount Holly, about 15 miles from Charlotte, local officials launched an intensive effort more than a decade ago to revitalize the downtown, developing a comprehensive development plan as well as putting a mixed-drink referendum on the ballot. In 2003 voters in the town of nearly 14,000 approved it 2-1. Officials recently approved a 10-acre mixed-used complex along the Catawba River, which is drawing interest from large restaurants.

“I think you have to look at it holistically,” says Mount Holly Planning and Development Director Greg Beal. “If you pass liquor-by-the-drink, you’re not going to get an Applebee’s or Chili’s lined up immediately. You have to do other things. But we know they’re not coming without alcohol, because that is a large part of their sales.”

A complicated history

In North Carolina, the prohibition and sale of alcohol has a complicated, volatile history.

As a result of a powerful temperance movement, the state was the first in the South’s Bible Belt to prohibit alcohol sales, more than a decade before the 18th Amendment banned it nationwide in 1920. North Carolina was not among the states to ratify the 21st Amendment, which ended prohibition in 1933.

|

For chart showing alcohol sales in the Charlotte region, see below. |

Four years later, the state set up the Alcohol Beverage Control system, under which the state controls the distribution of alcohol and voters decide if they want alcohol sold in their communities under the authority of local ABC boards. Revenue from ABC store sales boosts the coffers of state and local governments.

In the 1970s, the question of whether to give local jurisdictions authority to vote on mixed drinks ignited fierce political battles in the state legislature. A heavily negotiated law passed in 1978, despite tough opposition from anti-liquor forces, which ended the longtime practice of brown-bagging. (To learn more about the 1978 vote, see “How Charlotte Got Liquored-Up” by Chuck McShane.)

Today, only one N.C. county is completely dry: Graham County in the western part of the state.

“Since the recession,” says Herring of the ABC commission, “we’ve seen a lot more areas, particularly in the western part of the state, put the issue on the ballot because of the revenue potential and the economic development potential. In the majority of the areas, it was approved.”

Nevertheless, opposition remains from some residents, who argue the sale of alcohol in stores and restaurants damages community morals. But during nearly two decades of fast growth, planners say, the influx of people from states with fewer restrictions on alcohol has helped soften that sentiment.

Last year, 11 municipalities and three counties held referendums on the sale of alcohol, including four towns in the Charlotte region. In all of them, residents approved either beer and wine sales, or liquor-by-the-drink or opening ABC stores.

Voters in Ranlo, a town of nearly 4,000 in Gaston County, last November rejected ABC stores and the sale of beer and wine in stores but approved liquor-by-the-drink. State law allows restaurants with mixed beverage licenses to sell beer and wine.

“Some officials were looking at the potential for drawing either a grocery store or a convenience store,” says Charles Graham, the town coordinator. “All around our town limits, there have been convenience stores built and restaurants opening. But none of them have come to us.”

N.C. alcohol sales in the Charlotte region