Home ownership and the legacy of redlining

This is the third in an ongoing series, based on a report by the Urban Institute. The report was compiled with support from Bank of America, which partners with the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and the Institute for Social Capital on research that provides insight into community initiatives. Join us Wednesday at 7:30 p.m. on Twitter for a discussion, using the hashtag #WealthGapWednesdays to follow along and ask questions.

Wealth is not built through a single pathway. Individuals and families build wealth through a combination of assets that grow over time and across generations.

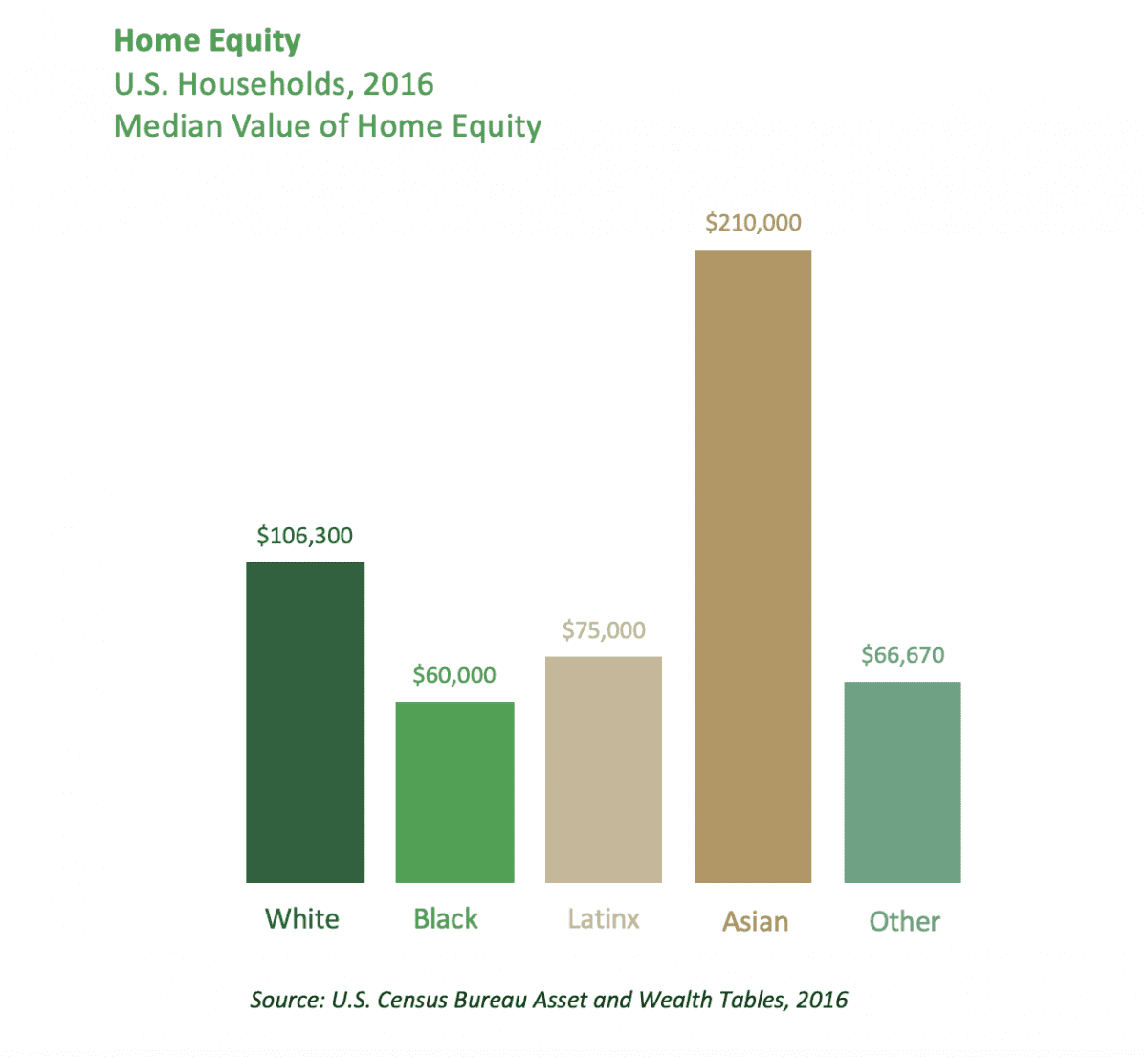

Home ownership is one of the key strategies to close the racial wealth gap. A home is where households see gains in equity (market value of home minus any liens attached to property) and is typically the largest asset Americans hold, regardless of race or ethnicity.

But Black and Latinx households have considerably less equity in their homes than White and Asian households. As Richard Rothstein says in The Color of Law, “A home is one of the only assets where the race of the owner affects the rate of return.”

Several factors ripple across decades to impact the value of home ownership for Black and Latinx families. Home equity grows as the value of a house increases. But homes exist within neighborhoods, and it is the neighborhood, in large part, that ultimately determines home value. The legacy of redlining, in which entire neighborhoods were designated undesirable and choked off from financing and investment, has locked many Black and Latinx families out of this key wealth accumulation pathway.

[The Racial Wealth Gap in Charlotte-Mecklenburg: Read the new report]

Legacy of redlining

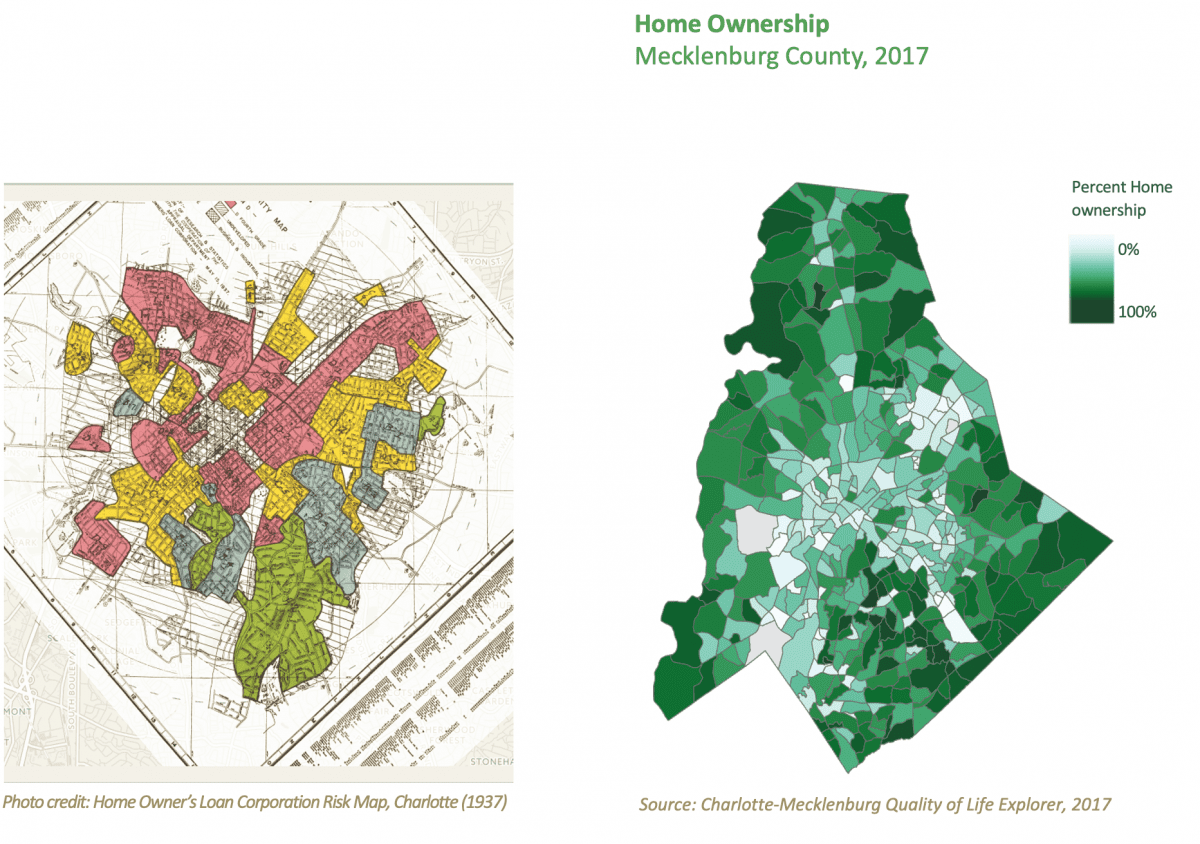

In an effort to standardize credit analysis across the nation in the 1930s, the Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) mapped urban neighborhoods according to perceived credit risk. The neighborhoods deemed high risk appeared red on the map while those with the lowest risk were colored green. According to Charlotte historian Tom Hanchett, “four areas won the coveted A [green] rating: Myers Park, Eastover, and the Olmstead portion of Dilworth, all in the southeast sector, and a small tract adjoining the Charlotte Country Club to the northeast.”

| The Racial Wealth Gap |

| Part 1: COVID-19 exposes the impact of the racial wealth gap |

| Part 2: The historical roots of the racial wealth gap in Charlotte |

In practice, only high- and middle-income white neighborhoods received the highest ratings. African-American neighborhoods were automatically deemed bad credit risks and received the worst ratings — and were colored red on the maps lenders used. This practice of redlining deterred investors away from Black neighborhoods and steered investment towards “low-risk” White neighborhoods, depressing the housing market in Black communities.

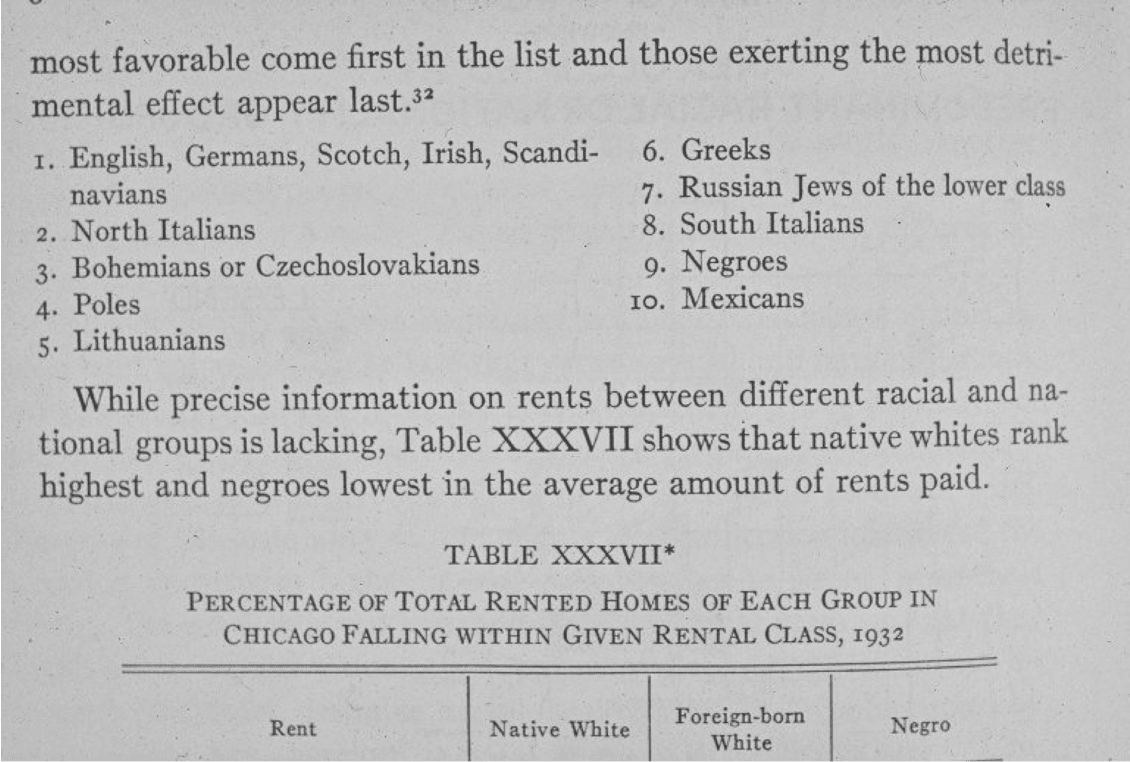

Photo: Tom Hanchett; Page 316 from Homer Hoyt’s 1933 dissertation that informed federal housing policy

Photo: Tom Hanchett; Page 316 from Homer Hoyt’s 1933 dissertation that informed federal housing policy

Not only did redlining depress housing values in black neighborhoods, it also barred families of color from obtaining loans to purchase homes. Homeownership as a pathway to wealth was not a possibility for these families. Redlining thus erased the opportunity for households of color to accumulate wealth through homeownership to pass to future generations. The impact of these practices can be seen even today in the form of dramatically higher home ownership rates and prices in those neighborhoods colored green so many decades ago.

The foreclosure crisis that led to the Great Recession in 2008 followed the same redlined boundaries and the decades of speculation and predatory lending practices that maintained them. Despite claims that Black families, undocumented immigrants, and other “risky borrowers” were at fault, renters and owners in Black and immigrant neighborhoods were targeted for more expensive loan products and higher interest rates. Further, White investors were often responsible for high foreclosure rates in Non-White neighborhoods compared to White neighborhoods.

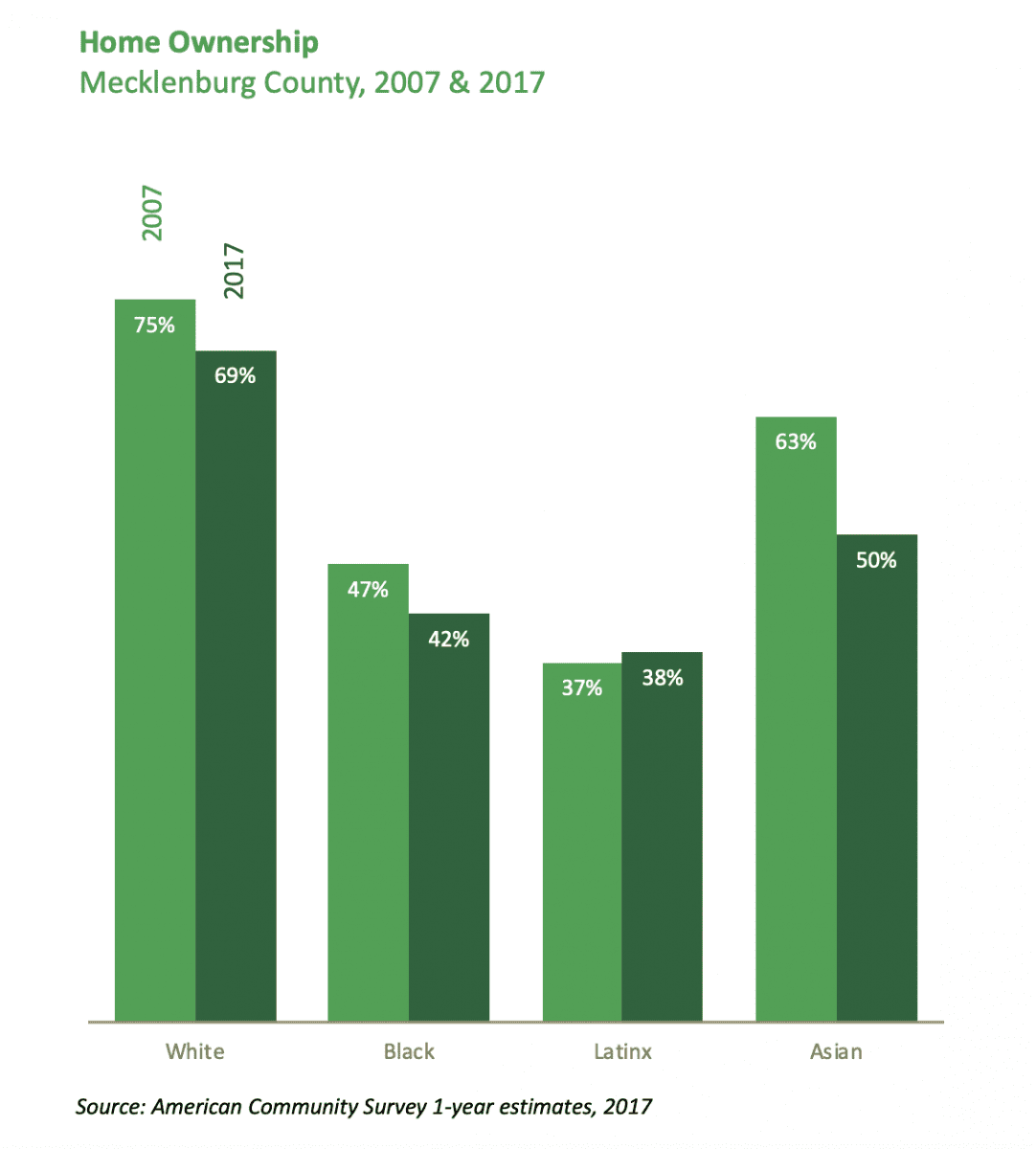

Disparities that last for generations

Racial disparities stemming from redlining and other housing policies instituted decades ago have persisted over time. White households are more likely to own their homes in Mecklenburg County when compared to other racial and ethnic groups. In 2017, over two-thirds of White households owned their home. A smaller portion of Asian (50%), Black (42%) and Latinx (38%) households owned a home at that time.

Homeownership rates in Mecklenburg County continue to reflect redlining practices enacted in the 1930s. Areas once deemed too risky for investment because of racially driven policy still have the lowest home ownership rates in 2017. Policies such as redlining and urban renewal left historic African American neighborhoods economically and physically devastated and wiped out others like Brooklyn.

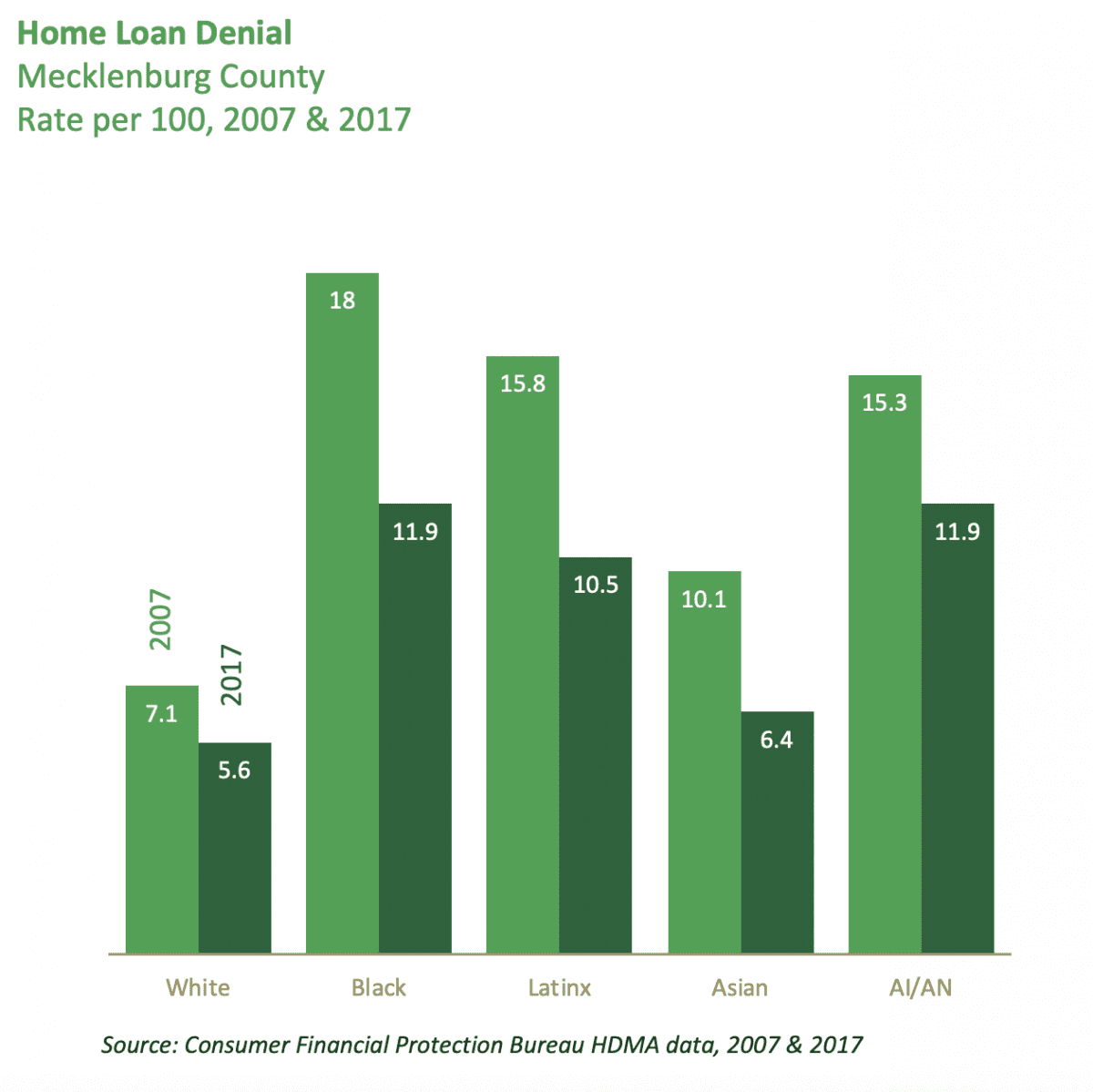

Today, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous applicants are still denied home loans more often than White and Asian applicants in Mecklenburg County. These disparities can be connected to lack of sufficient income, less access to intergenerational wealth for down payments, and discriminatory lending practices (Note: numbers do not control for denial reasons such as debt-to-income ratio, credit score, and available cash).

Home Ownership and Housing Policy Solutions

Building wealth and establishing a safety net for all households is even more pressing today, given the global pandemic we currently face. Home ownership is a large part of that wealth and takes on greater significance as homes function as safe havens, schools, and workplaces.

In addition to Baby Bonds and other efforts to address the racial wealth gap, specific home ownership and housing related reforms should be considered. Housing and lending practices which limit the asset appreciation of the housing stock and financial products available to certain populations need to be addressed. For further reading on possible solutions, check out these sources:

- Prosperity Now: Enhancement and enforcement of fair housing practices

- Great Democracy Initiative: Modern Homestead Act

Due to the structural, multifaceted and cumulative nature of wealth, home ownership alone will not close the racial wealth gap. However, reversing decades of discrimination in the housing market will address one primary cause of wealth inequity. It will require concerted effort to address the housing and lending practices that limit what is available to Black and Latinx populations.