How jobs contribute to the racial wealth gap

This is the fourth in an ongoing series, based on a report by the Urban Institute. The report was compiled with support from Bank of America, which partners with the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute and the Institute for Social Capital on research that provides insight into community initiatives. Join us Wednesday at 7:30 p.m. on Twitter for a discussion, using the hashtag #WealthGapWednesdays to follow along and ask questions.

“Income allows a family to get by; wealth allows a family to get ahead.”

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Wealth Inequality in America.

COVD-19 has cost tens of millions of jobs and decimated whole industries. The jobs that have survived have been fundamentally changed, with a focus on sanitation that alters workflow or with millions of people suddenly working from home. But one thing remains unchanged: COVID-19 is likely to worsen already large disparities in income and industry across race and ethnicity.

Income is a major component of wealth, but the relationship between income and wealth is complex. Wealth and income are both used to measure a family’s economic situation, but they tell us different things about the health and strength of economic well-being.

[The Racial Wealth Gap in Charlotte-Mecklenburg: Read the new report]

Income (the amount of money a household or individual makes in a year) indicates short-term economic health, while wealth (total assets minus liabilities) measures economic strength in the long term. Households living with higher incomes can dedicate larger shares of their income toward accumulating wealth through various investments, which ultimately results in higher gains in net worth. But income alone doesn’t guarantee wealth, as unexpected expenses and setbacks can wipe out economic gains for families that don’t have much of a cushion.

| The Racial Wealth Gap |

| Part 1: COVID-19 exposes the impact of the racial wealth gap |

| Part 2: The historical roots of the racial wealth gap in Charlotte |

| Part 3: Home ownership and the legacy of redlining: Charlotte’s racial wealth gap |

Wealth is multifaceted, cumulative, and structural. The racial wealth gap cannot be explained by income alone; income disparities are large but wealth disparities are much larger.

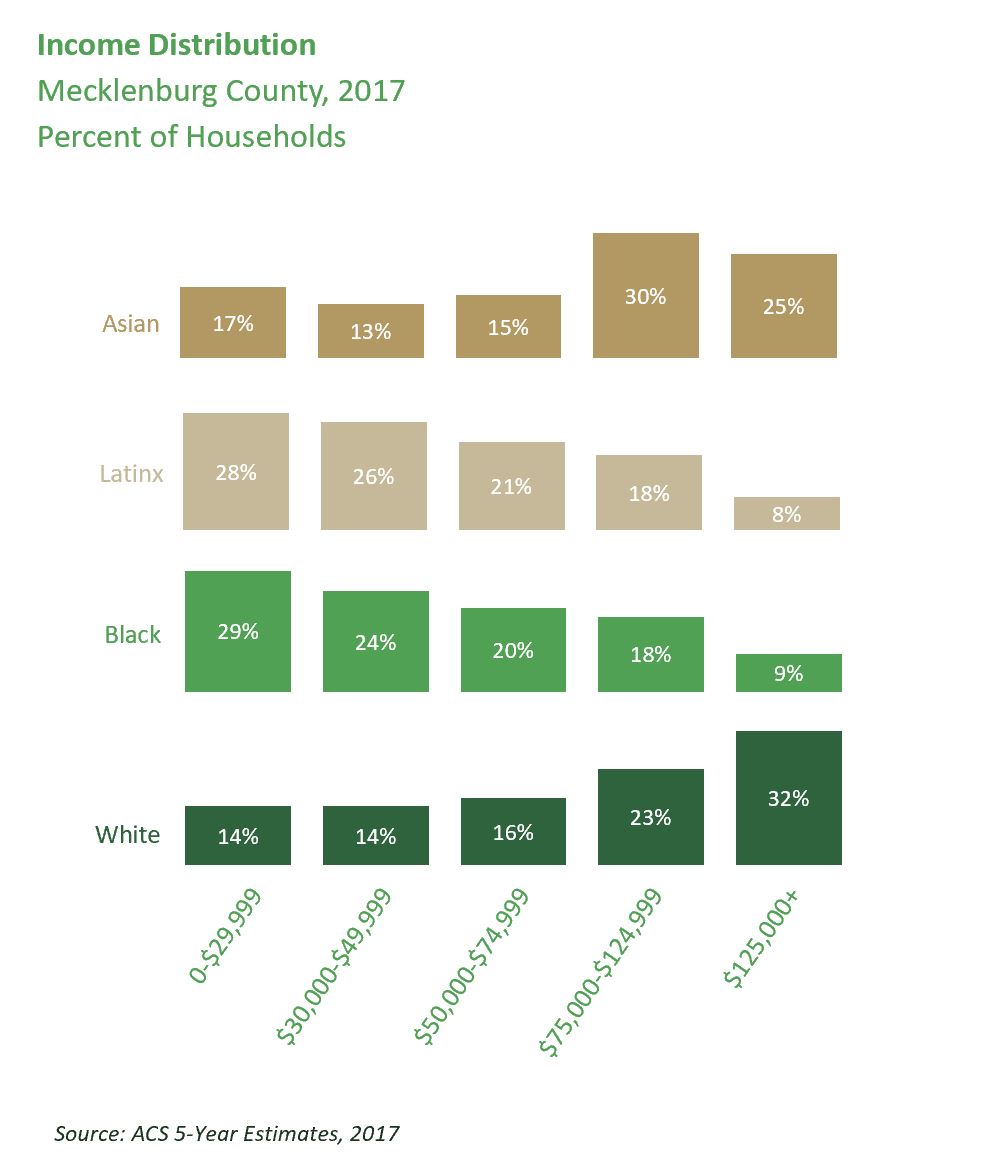

On average, White and Asian household incomes in Mecklenburg are double that of Black and Latinx households. In Mecklenburg County, about a third of White households and a quarter of Asian households live with incomes in the top quintile, while less than ten percent of Black and Latinx households are represented in the highest income bracket, according to the most recent data from the American Community Survey.

Industry’s stronghold on income and earnings

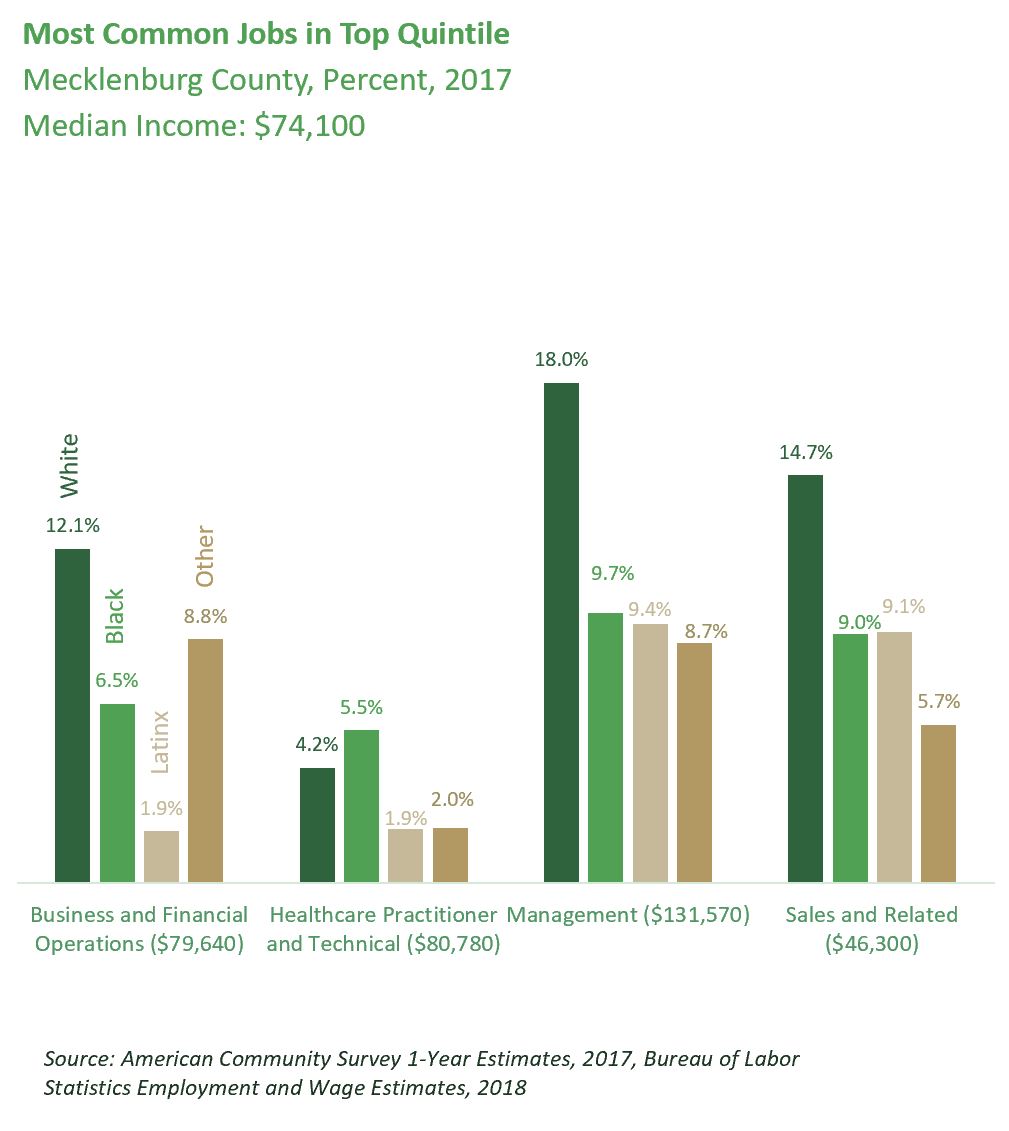

The industry in which one works strongly influences earnings. Industries like food service and maintenance have much lower average annual earnings than industries like healthcare and management. Industry type and earnings are also tied to education and skills and the industries with the highest average earnings have traditionally been viewed as higher value jobs.

COVID-19, however, has shifted that perception, at least temporarily: Workers in food service, sanitation, and child and elder care are designated as “essential employees” that support us through this pandemic.

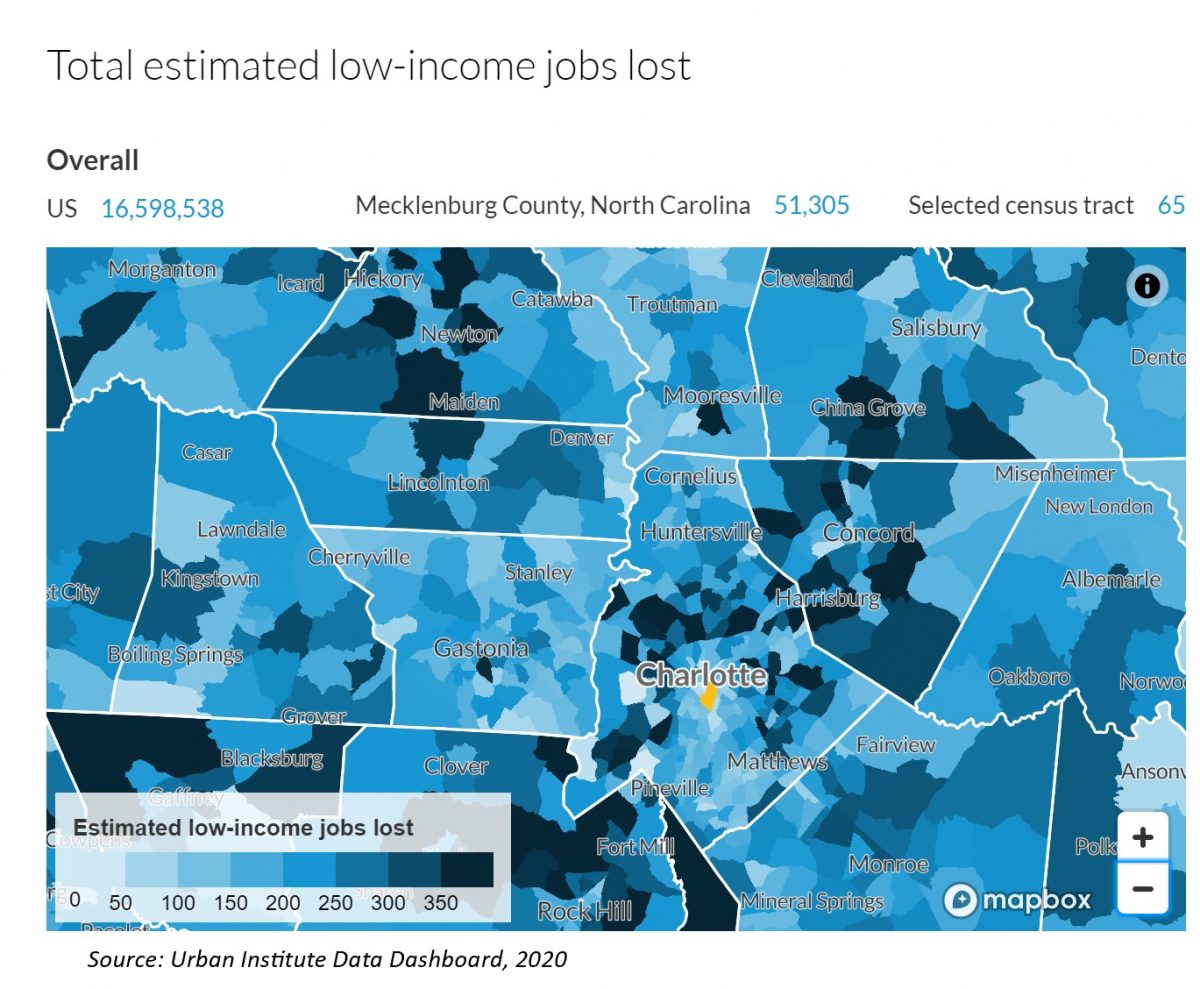

The most common jobs with the lowest average salaries in Mecklenburg County are building and grounds maintenance, food preparation and service, office and administrative support, and production, many of which are deemed essential during the COVID-19 pandemic. Black and Latinx people make up a larger share of these jobs when compared to White employees. Grounds maintenance, food preparation, service and production employees are more susceptible to the COVID-19 virus, as these industries often require their employees to leave their homes and come into work.

And these employees are more likely to lack sufficient income and health benefits to provide them with a safety net if they do fall ill. These individuals are likely to incur more debt when faced with hospitalization or illness, thus widening the racial wealth gap further.

It’s the reverse for the jobs with the highest pay, such as business, financial operations and management where White individuals make up the majority of workers. Workers in these industries are more likely to work from home during the pandemic. The exception is healthcare jobs, the essential industry in these times, where Black workers slightly outnumber White workers.

While millions of jobs have been lost, some industries are getting hit harder than others. Many businesses with low-wage employees, such as restaurants and hotels, have been forced to shut down and permanently or temporarily lay off their employees, with more impacted every day. Many of these “at-risk” industries have employees that make less than $40,000 a year. It’s estimated that Mecklenburg County is losing more than 51,000 of these jobs due to COVID-19, mostly in accommodations and food services.

Economic mobility and wealth

In Mecklenburg County, only 2.6% of Black children born in the lowest income quintile will make it to the top quintile. For White children in the same situation, 12% will move to the top income quintile as adults, making the upward mobility rate for White children in Mecklenburg County comparable to some of the most mobile places in the country.

Local efforts to change this statistic and the poor national ranking that accompanied it have primarily focused on income. While important to address, wealth offers a more comprehensive lens to examine economic mobility in our region and nationally. Wealth is much less volatile than income and typically stays with those who already have wealth built across generations. Wealth is made up of several compounding factors, including income. Approaching economic mobility through a wealth lens, rather than just income, is critical to addressing inequality.

While COVID-19 did not create the racial and ethnic disparities in income and industry we see in Charlotte and across the country, it has exposed where and who our systems are failing the most. As parts of the country begin to reopen and slowly resume “normal life” we can choose to better our systems so that people are supported equitably.

Income and Industry Policy Solutions

Addressing inequality in income and industry, and ultimately the racial wealth gap stemming from these inequalities, depends on solutions that focus on fixing systems, not people. Proposals include using a targeted universalism approach, combining solutions within and across systems, and focusing on solutions that can stretch across generations.

In addition to baby bonds and other financial efforts to address the racial wealth gap, specific income and industry policy solutions should be considered. The solutions outlined below include policy changes and evidence-informed practices from subject matter experts that bridge racial and ethnic gaps in income and industry, components of the racial wealth gap.

Universal Basic Income (UBI): UBI proposals guarantee a minimum, regular income per individual. The income, its frequency, and duration vary by proposal. UBI proposals address poverty alleviation and the lack of income to meet basic needs but do not alone address wealth disparities.

- Stanford Basic Income Lab: A review of Basic Income Experiments

- Disrupting the Racial Wealth Gap by Melvin Oliver and Thomas Shapiro

Federal Job Guarantee: These proposals provide universal job coverage to individuals that are seeking employment. A minimum wage would be over the poverty level and indexed to inflation. A national jobs corp would provide socially useful goods and services, including physical and human public infrastructure.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: The Federal Job Guarantee – A Policy to Achieve Permanent Full Employment (2018) by Mark Paul et al.

Criminal Justice Reform and Smart Decarceration: These strategies aim to reduce disparities in sentencing and incarceration, including programs that prepare returning citizens for life outside of prison or jail.

- Institute for Justice Research and Development: Guideposts for the Era of Smart Decarceration by Carrie Pettus-Davis et al.

- The Rand Corporation: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs that Provided Education to Incarcerated Adults by Lois Davis et al.