How zoning shapes your daily life, even if you don’t know it

As you may be aware, Charlotte is beginning a long-overdue rewriting of its zoning ordinance. To be sure, zoning tops many people’s list of the most boring and obtuse topics. So it’s easy to understand why this multiyear process might fail to generate much public enthusiasm or desire to participate. But zoning is much more important than most people realize. It’s the “invisible web” of regulations that dictate the form and functionality of every American city.

Zoning literally shapes our daily lives, sometimes for better, often for worse.

So here’s a question: “Do you want the framework of your life in Charlotte to be decided by a bunch of well-meaning but detached planning experts giving their highly paid advice to City Council … (If so, you can stop reading now.) … or do you want an informed say in this vital discussion about our city’s future?”

To be an effective participant, it’s important to know a few basic facts about the zoning we have now, where it came from, and how it could change. These changes are likely to introduce some new ways of thinking about city planning and design that differ from concepts that have held sway for the last hundred years.

This essay is the first of two on the topic. I’ll try to explain:

- What you need to know about current zoning practices.

- How and why they came into being.

- What is wrong with them for Charlotte in 2016 and why, most urgently, it’s time for a change.

- What some of the new ideas are.

The second essay outlines potential elements of a new approach to zoning and explain how new ways of thinking about zoning focus more on the character of neighborhoods and districts—what they feel like as “places”— than today’s zoning, which is based on the use of land or buildings. (See “Moving from zoning’s alphabet soup to describing real places.”)

To understand the degree to which conventional zoning dictates the rhythms, sequences—and financial costs—of our daily routines, consider: Tens, if not hundreds of thousands of people in and around Charlotte endure long daily work commutes in their cars. A large percentage also must fit many other activities into the day. Many readers will relate to the daily hassles of trying to do six or seven different things in the same 12- to 15-hour “working day”: taking kids to school, going to work, going to the doctor, stopping off for shopping, picking up kids, going to soccer practice and then some evening activities (if we have the energy).

Each activity is probably in a different location, and each requires time and energy to drive from one location to the next. That geographical separation is due almost entirely to modern zoning. Zoning makes the city look the way it does—which is one way it controls your life.

Zoning hits your wallet, too. The way things are separated and strung along highways forces many families to own at least two cars and buy a lot of gas. Apart from that expense, the way we live is proven to be bad for the planet. Per capita, our nation and our city consume four times our share of Earth’s resources. The future—our kids’ and grandkids’ future— does not compute.

Thus we have two questions: How did zoning get to be this way? And can it change so that it can provide us with choices for our lives that are more sustainable?

Traditional American cities were more compact, connected,and walkable, and were served efficiently by public transport. Think of somewhere like Salisbury, a city of about 33,000 people 45 miles northeast of Charlotte. Salisbury’s historic downtown, pictured above, contains shops, restaurants and bars, offices, different types of housing, a Town Hall and county courthouse, churches, banks, library, arts center and a working train station—all in a few concentrated blocks.

The changes to this historical pattern had their beginning in Modesto, Calif., in 1885. The white, middle and upper classes there created regulations to restrict laundries, operated exclusively by Chinese families, to poorer parts of town, away from white residential areas.

Ten years later, the city of Los Angeles established separate zoning districts for residential and industrial areas. Partly, this was common sense. It was unhealthy to live next to industry that might be spewing toxic fumes. But then Los Angeles went further. The city banned all business uses from residential districts. As those ideas spread to other communities in later decades, the fabric of traditional American town building began to unravel. No longer could places like historic Salisbury, where everything was mixed together, be built. Now everything had to be sorted out into separate land areas for separate uses.

Those changes were encouraged during the 1920s by the “Standard State Zoning Enabling Act” of 1924, a model ordinance for states offered by the U.S. Commerce Department, which set in motion zoning codes across the country that were strictly use-based. The presumption was that clarity and efficiency were good for business. The new zoning laws could have required new development to follow the historic pattern set in older American towns. But they didn’t.

To understand why, remember that as the nation picked itself up after the Depression in the 1930s, there was little interest in looking back at the hardships of history. The future beckoned—cleaner, efficient and mechanized. Cities began to be thought of as giant machines, and “efficiency” became the most important concept. Efficiency became synonymous with simplicity.

For builders, the most simple and efficient way to operate was by building only one particular kind of housing, such as single-family detached homes. Let someone else build apartments. Each developer became a specialist focused on a single product, be it housing, offices or shopping centers. Each type of development gained efficiency by simplifying its operation and excluding other kinds of buildings. In this way single-use zoning was a boon to the private sector. Land could be divided in advance for the different uses that—if you put them all together—would have made a town. But as they were legislated and built apart from each other, the physical fabric of urban America was progressively dismantled.

We started living our modern lives in separate compartments.

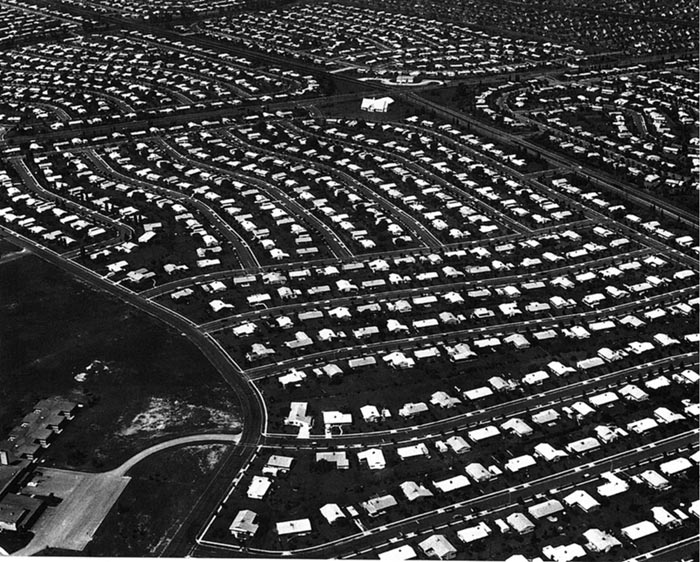

This dissolution of America’s traditional communities in the name of an optimistic, technologically based future was hastened by the development of one particular new technology: the motorcar. After World War II, cities were planned for the automobile. Different pieces of the city could now be spread widely apart; it still took only a few minutes to go from one to the other, so long as you traveled 30 mph or more—easy on the wide, new roads. To accommodate all the new cars, mid-20th– century zoning codes required large parking lots, covering the growing suburban landscape with tens of thousands of acres of asphalt.

By the 1950s and 1960s the zoning innovations of the 1920s became locked into proscriptive legislation. Most municipal zoning codes in America today are still based on the approach set out in that model legislation from 1924. Those concepts hardened into dogma 50 years ago and have since been plastered with countless “Band Aid” amendments, trying to keep abreast of change.

So it’s long overdue for Charlotte’s zoning to change, as it has in other American cities such as Denver, Miami, Nashville and, closer to home, Raleigh.

To whet your appetite for part two, think about places in towns and cities that you like, even love. Think through what makes these places special—not generalities (like “the weather” or “friendly people”) but specifics about the place: sizes of spaces and buildings, combinations of uses, details of streets and parks you like. Describe to yourself what different types of places you like. Try to list how many different types of places you like—not just different locations but different categories of places, such as what happens there, how it looks and how you feel about it.

Once you’ve done that you’ll be partway along the path Charlotte’s new zoning ordinance will likely travel. It’s likely to be based not on abstract definitions and formulas keeping everything separate, but on “place types,” similar to the ones you’ve described to yourself. These “place types” help define and create what we call “community character,” the features by which we recognize and identify our neighborhoods and districts.

For example, Charlotte’s South End clearly has a different “community character” than the distinctive neighborhood of Myers Park. The new kind of zoning rules for development in those two areas would highlight different qualities and require different arrangements of buildings and spaces to fit with their special, “place-based” characteristics.

Two quick examples may help clarify what “arrangements of buildings and spaces” means.

The photo above shows a block of urban apartments in South End beside the light rail line and the pedestrian-bicycle “Rail Trail.” The building is close to the public trail, defining a clear edge to public space. But this proximity raises conflicts between the public outdoors and the private indoors. To resolve this, an effective “arrangement of buildings and spaces” creates a threshold, or transition, between the exterior public space and the private interior of the ground-floor dwellings. The transition is shaped by a change of level, railings with a gate and hedges enclosing patios. Here, residents can sit in semi-seclusion and watch the world go by, while still being outdoors. It’s a well-designed, semi-private “stoop” as an urban alternative to a porch.

The photo above shows a typical street in Myers Park, one of Charlotte’s most prestigious neighborhoods, designed as a suburb by landscape architect John Nolen in 1911. The “arrangement of buildings and spaces” is different. Boundaries between the public space of the street and the private space of the home are blurred and extended by a large, semi-private front yard that is privately owned but visually accessible to public view.

Whereas the “urban” example is relatively complex in order to resolve conflicts between public and private realms in a small space, the “suburban” example can use fewer design elements and rely on distance to provide privacy to the interiors.

Those are two illustrations of “place-based” thinking and “community character”—describing a district or a neighborhood based on its constituent “place types.”

Part two of this series will describe “place types” in more detail. I’ll explain where they come from in the recent history of planning and urban design, how they are used, and how they can map a brighter and more sustainable future for Charlotte.

David Walters is an architect and town planner and a UNC Charlotte professor emeritus who recently retired as director of the university’s Master of Urban Design program. Opinions in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.