The impact of the racial wealth gap in Charlotte-Mecklenburg

This is the first in a series, based on a report by the Charlotte Urban Institute. Read Part 2 here. The report was compiled with support from Bank of America, which partners with the Charlotte Urban Institute and the Charlotte Regional Data Trust on research that provides insight into community initiatives.

By James E. Ford, Ph.D., and Lori Thomas, Ph.D.

Race shapes how people experience the coronavirus pandemic, as do wealth and the systemic disparities that have resulted in a racial wealth gap. If you have wealth — assets like income, a home, and savings that are greater than what you owe — you can reasonably protect yourself and your family from the most devastating physical and economic impacts of the virus (i.e. by staying home, covering your expenses if you lose income, etc.).

If you don’t have wealth, you are more likely to suffer the pandemic’s worst outcomes.

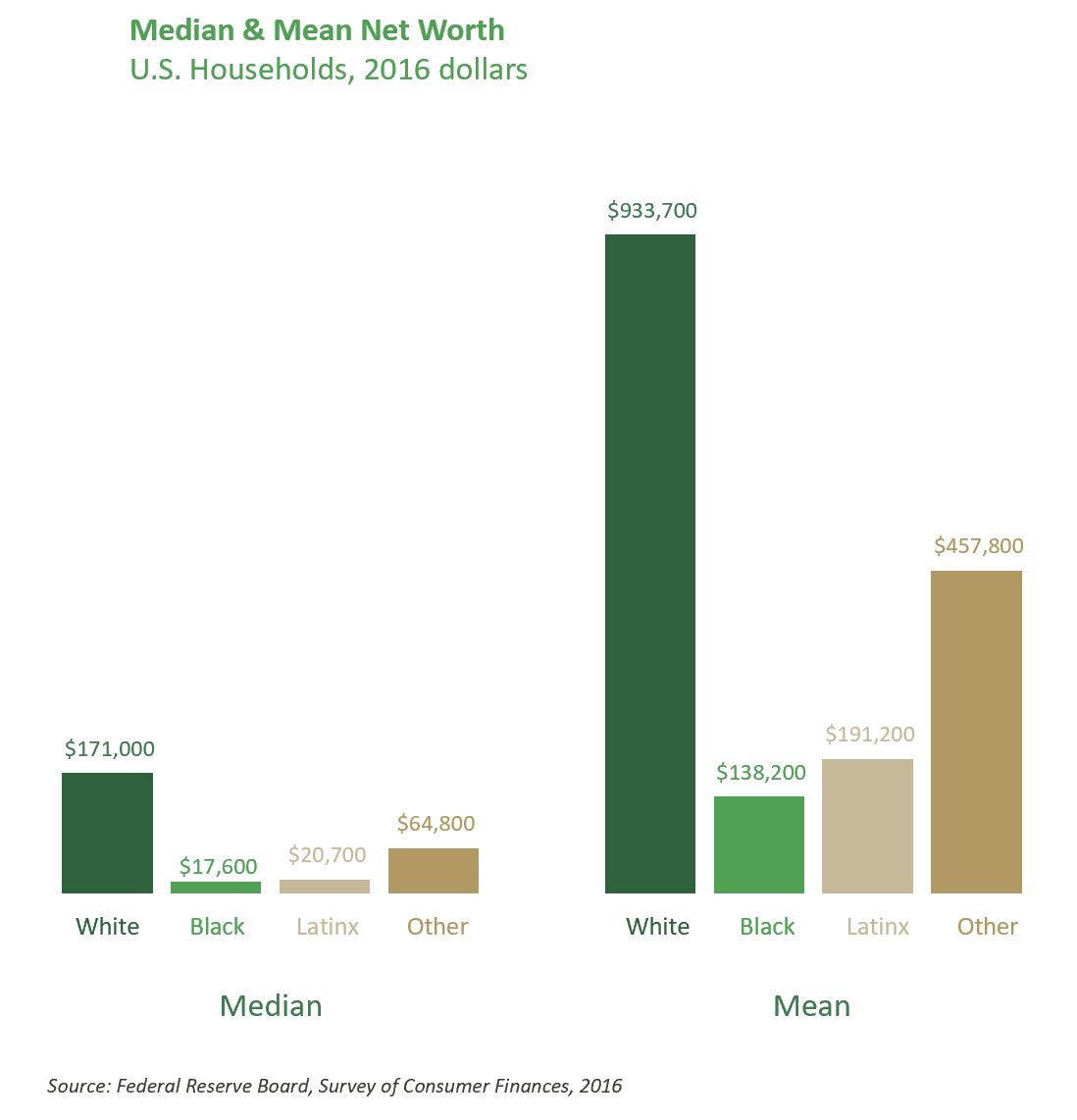

In the United States, White households have 10 times the wealth of Black households and 7 times the wealth of Latinx households. This has not occurred by mere happenstance. Wealth is built through a combination of pathways, each with its own history of policy and practice. The consequences enhance or hinder asset building across racial and ethnic groups.

The systemic patterns of racial inequity that lead to such stark differences in wealth accumulation are the same well-worn paths that lead to unequal outcomes in labor, housing, education, and health.

This problem is engineered and evident in the impact of the coronavirus. Black and Latinx people are more likely to work in many jobs deemed essential like grocery clerks and poultry workers and underrepresented in management and other white collar professions that are more likely to continue working remotely in safety. In addition, Black and Latinx workers are more likely to hold jobs that do not provide access to healthcare or paid sick leave.

White Americans are more likely to be homeowners and are less likely to live in crowded housing or in homelessness. Reflecting disparities in the social determinants of health, Black and Latinx Americans have higher rates of underlying diseases like diabetes and heart disease that increase the risk of dying from COVID-19.

During this period of social distancing, wealth is both a shield from and a reflection of the systems that create and sustain disparate virus outcomes. The novel coronavirus is a stark reminder of why it’s key to close the racial wealth gap as well as change the systemic patterns that created it.

| The Racial Wealth Gap: Read the full series |

| Part 1: COVID-19 exposes the impact of the racial wealth gap |

| Part 2: The historical roots of the racial wealth gap in Charlotte |

| Part 3: Home ownership and the legacy of redlining: Charlotte’s racial wealth gap |

| Part 4: How jobs contribute to the racial wealth gap |

| Part 5: Business ownership and entrepreneurship |

| Part 6: Savings, investment and the racial wealth gap over generations |

| Part 7: Myths about closing the racial wealth gap |

Today, the Charlotte Urban Institute released a report on the racial wealth gap, including local data on Charlotte-Mecklenburg. The report describes the gap and patterns across the various components of wealth that lead to differences in wealth accumulation. The report was compiled with support from Bank of America, which partners with the Charlotte Urban Institute and the Charlotte Regional Data Trust on research that provides insight into community initiatives.

[The Racial Wealth Gap in Charlotte-Mecklenburg: Read the full report]

For the next six weeks, on #WealthGapWednesdays, we will focus on a different section of the report on the Institute website. Each Wednesday evening at 7:30 p.m. beginning May 13, 2020, James Ford and Ely Portillo will moderate a Twitter chat about the topic, including local guests to provide deeper insight into the problem and solutions.

- May 13, 2020: Our shared history. The wealth of White households is 10 times greater than Black households and 7 times greater than Latinx households. How did we get here?

- May 20, 2020: Home ownership and the legacy of redlining. Home ownership has long been the largest component of wealth for Black and Latinx households, but the median value of equity in those homes is substantially less than that of White and Asian households.

- May 27, 2020: Income and industry. On average, Black and Latinx households earn half the income of White and Asian households. Black and Latinx workers are overrepresented in lower paying industries and underrepresented in higher paying industries, based on calculations from American Community Survey and the Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

- June 3, 2020: Business ownership and entrepreneurism. The median net worth of Black and Latinx business owners is more than 10 times that of their peers who don’t own a business, yet White people are more likely than any other group to own their own business and own a business with employees.

- June 10, 2020: Savings, investments, and intergenerational transfer. According to research by Darrick Hamilton and Ngina Chiteji, Black families save at the same rate as White families when controlling for income, yet many efforts to address the racial wealth gap focus on financial behavior and soft skills instead of the structure of work, access to financial services, and the role of intergenerational wealth transfers.

- June 17, 2020: Education as equalizer and other assumptions about closing the gap. Education is supposed to level the playing field, but on average the net worth of Black households headed by a college graduate is $30,000 less than White households whose head does not have a bachelor’s degree.

For the last five years, Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s public and private sectors have focused on addressing residents’ economic mobility, specifically the ability for low-income Charlotteans to increase income across generations. That focus sharpened after research by Opportunity Insights led by economist Raj Chetty found economic mobility in our commuting zone ranked last among the 50 most populous commuting zones in the country.

Like much of the research, our local efforts to address economic mobility have focused primarily on income and not wealth. Wealth is another, more comprehensive lens to examine economic mobility. The racial wealth gap points to the cumulative impact of inequity across multiple pathways of asset accumulation including income, but also home ownership, education, business ownership, retirement, and other savings and investment accounts.

To address the racial wealth gap is to change the systems and structures that have created and now sustain it — the same systems that determine COVID-19 outcomes. The pandemic is a sobering reminder that although a crisis is experienced by all, it is not experienced equitably.

About the Authors

James E. Ford, Ph.D., is the executive director of the Center for Racial Equity in Education and Lori Thomas, Ph.D., is the executive director of the Charlotte Urban Institute and Charlotte Regional Data Trust.

This article was updated on January 17, 2025.