Island biogeography and the Uwharrie Trail

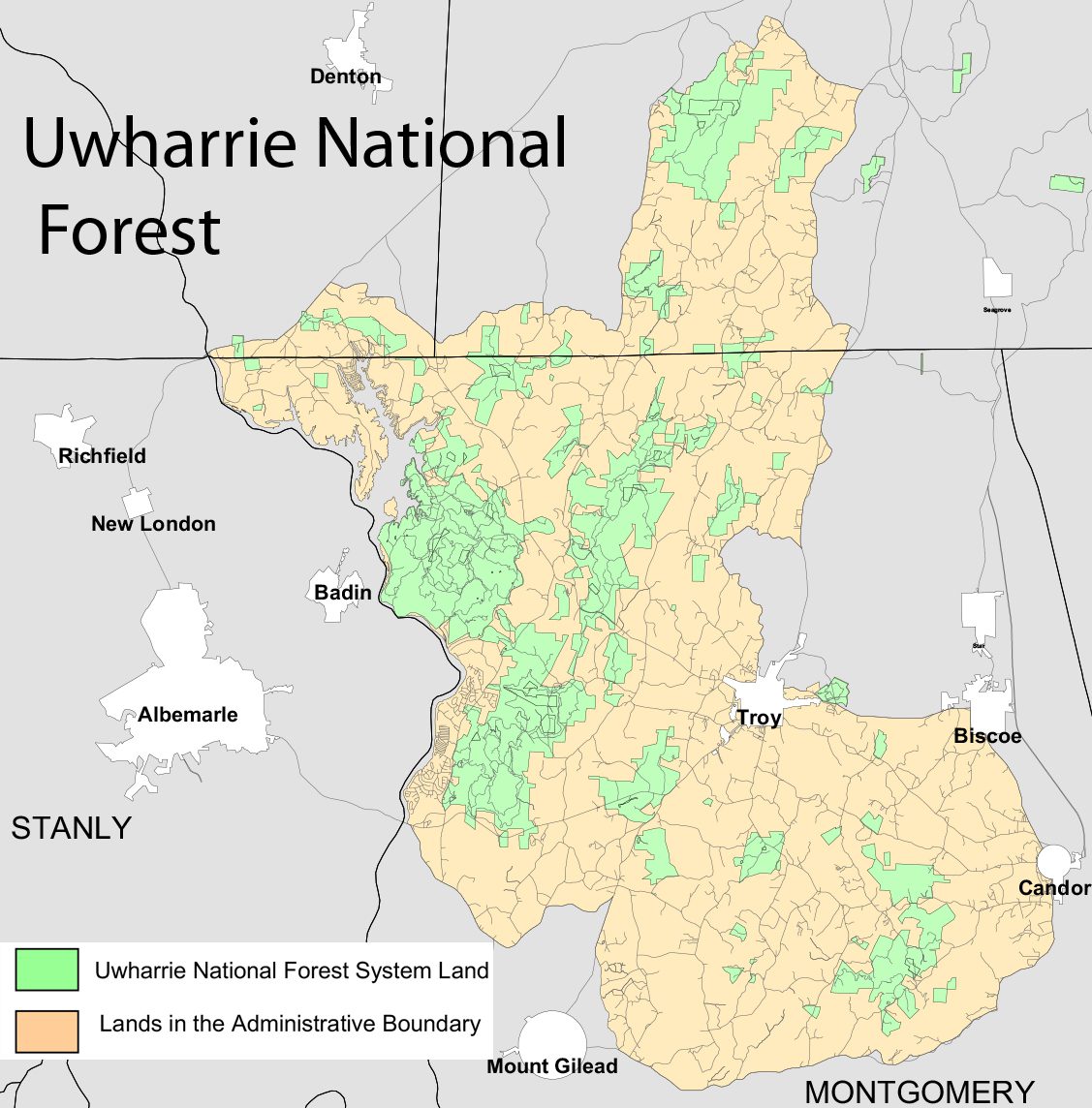

Your average roadmap of North Carolina represents the Uwharrie National Forest as a large, green blob covering most of Montgomery County as well as portions of Randolph and Davidson. In fact, that’s simply the proclamation boundary. Look at a detailed map of the national forest, and you’ll see a crazy patchwork of light and dark tracts. Less than a quarter of the area inside the proclamation boundary is actually owned by the U.S. Forest Service. In addition, the major holdings aren’t contiguous. The Badin Recreation Area and the Uwharrie Trail corridor are connected by a thread, but neither one touches the Birkhead Wilderness Area. They’re surrounded by dozens of smaller, isolated tracts. In a sense, the Uwharrie National Forest is an archipelago, a cluster of islands in a sea of private property (see map below).

In the 1970s, local Boy Scout leader Joe Moffitt had a vision of extending the Uwharrie Trail from its terminus on Flint Hill Road northward to the Birkheads, a distance of roughly seven miles as the crow flies. He worked to secure agreements with private landowners in the area, then he and his troops established an informal trail linking the two. Scouts from across the Piedmont regularly used the trail for backpacking and long-distant hikes. Over the years, agreements fell by the wayside. Land changed hands and Joe moved into retirement. The connector trail fell apart, as if a land bridge between two islands had vanished beneath a rising tide.

This image is useful for understanding the theory of island biogeography. Developed in the 1960s to explain the species richness of actual islands, it has since been applied to a variety of natural areas isolated by a different type of ecosystem or a human-altered landscape. Think of mountains surrounded by deserts or forests fragmented by subdivisions or clear-cuts. The theory suggested a single large, contiguous tract of conservation land was better able to preserve species richness than several small, isolated tracts. This thinking spurred efforts to establish habitat corridors between nature preserves. David Quammen fleshes out these ideas in Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinction, a daunting title for a lively book. (In a passage that made me laugh out loud, he describes a ground-breaking dissertation being photocopied again and again until it becomes “grainy and bad, like home dubs from a bootleg recording of Bob Dylan performing half-drunk at a local bar.”)

Dr. Rob Bierregaard, a professor of biology at UNC Charlotte, makes an appearance in the book as the field director for a project sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution to study the effects of forest fragmentation. In 1979, he was sent to an area of Brazil that was about to be converted to pastureland. His team gathered baseline data on the species of flora and fauna present before the forest was cleared. Afterward, they went back and surveyed the isolated tracts of forest which ranged in size from 1 to 100 hectares. Over time, an unexpected variable was introduced – many of the cattle pastures were abandoned and left to revert to second-growth forest. This added a new dimension to their studies. They were able to assess not only the size and shape of particular tracts but also the effects of land use on the surrounding tracts. They found the interaction between the two can sometimes be more important than the size of the reserve.

These lessons from island biogeography are playing out on the ground in the Uwharries. The LandTrust for Central North Carolina is working to protect a corridor and establish a permanent trail between the Birkheads and the rest of the Uwharrie Trail. Other nonprofit groups and government agencies are focused on improving land use on adjacent tracts, helping landowners maintain Piedmont prairies and restore longleaf pines.

With public-private partnerships like this, perhaps we can, in fact, view that large, green blob on our roadmaps as a cohesive unit. On a landscape scale, the Uwharries are an island of exceptional habitat in the Piedmont. In addition, the eastern edge of our region transitions to the Sandhills ecosystem. This juxtaposition is unique in the Piedmont. I’m still dumbfounded the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, which will eventually run from Clingman’s Dome to Jockey’s Ridge, took shape along a northern route across the center of the state, following the Urban Crescent from Greensboro to Raleigh. It would be nice to see a southern loop added to the plan, one that establishes a permanent corridor between two vital eco-regions, the Sandhills and Uwharries.

Many thanks to Dr. Rob Bierregarrd, Deborah Walker, David Gardner, Ray Rimmer and David Craft for assistance with this article.