Islay Walden’s Uwharries story is relevant today

Here we are in the midst of graduation season. Even though the school experience has been different for the past year, young people are still celebrating this milestone and figuring out what to do with the rest of their lives. In rural areas like the Uwharries, that often means leaving for opportunities in other places. And yet, some find reasons to return. Ties to family and community, or the love of the rural lifestyle and landscape. For Islay Walden, a noted 19th century African American poet, there was also a higher calling.

As Margo Lee Williams writes in her new book, Born Missionary: The Islay Walden Story, “It was faith that would lead him back to New Jersey and the New Brunswick Theological Seminary. It was his love of family and community that would eventually lead him back to Randolph County, to be their teacher and pastor.”

Much has been written about Walden’s poetry. His work was included in a collection of literary classics that would eventually become the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City. Williams, however, wanted to explore Walden’s personal story. She had touched on him in her previous book From Hill Town to Strieby – which explored the role of the church and education in lifting up a rural, African American community – but realized there was much more to say about his remarkable life.

Photo courtesy Ruth Ann Grissom

Walden was born into slavery in Randolph County in 1844 and sold multiple times, eventually to Jesse Smitherman in Montgomery County. While enslaved, he worked in the region’s gold mines. Even though Walden remained on cordial terms with the Smitherman family – it was Smitherman who first recognized him as a poet – he was clear about the evils of slavery. As Williams observes, based on some of Walden’s poems, his faith also made him optimistic about the future of race relations. See the following verse from Walden:

“The races yet will come together,

In ties of love that none can sever.”

At the end of the Civil War, finally a free man in his early 20s, he was suddenly able to shape his own destiny. Nearly blind from birth – he could see shadows and shapes but lacked the visual acuity for reading – he’d always had an aptitude for memorization. He was determined to become a teacher. In 1867, he walked to Washington, DC, to attend Howard University. He received a generous scholarship to help pay for his education, but he also earned money from his poetry. Initially performing recitations, he began committing his poems to paper once he learned to read and write. After graduation, he attended New Brunswick Theological Seminary in New Jersey, where he would become the first Black man to both graduate and be ordained.

While there, “he started successful Sabbath school programs for children of color and a mutual aid society for the adults.” He also garnered attention from the local newspapers and even The New York Evening Post, owned by abolitionist William Cullen Bryant. Staying in the North would have been the easy career decision. Instead, he returned to the Uwharries in 1879 to the community then known as Hill Town, which he later renamed Strieby in honor of Rev. Dr. Michael Strieby, secretary of the American Missionary Association.

Early on, that association organized a circuit for Walden to deliver sermons around the region, including Troy where they were establishing Peabody Academy. A mere five years later, Walden would die of pneumonia. During his relatively brief time in Strieby, he founded a church, a school, and a post office. A longtime advocate for the temperance movement, he even helped persuade the General Assembly to pass “an Act to prohibit the sale of spirituous liquors within one mile of the Promised Land Academy in New Hope township…”

Walden had established a structure and system that allowed the community to flourish, even after his death. Ironically, his success eventually contributed to the community’s decline – many members left because they were equipped to pursue careers and higher education. Williams herself is a product of this dislocation. Her first book, Miles Lassiter (circa 1777-1850): An Early African American Quaker from Lassiter Mill, Randolph County, North Carolina, has a personal subtitle: My Research Journey to Home. Her mother, a Lassiter descendant, had moved to the Northeast as a young girl and had lost touch with her maternal relatives in North Carolina. Williams was well into adulthood before she would connect with those who had remained on the vast estate once owned by Miles and Healy Lassiter.

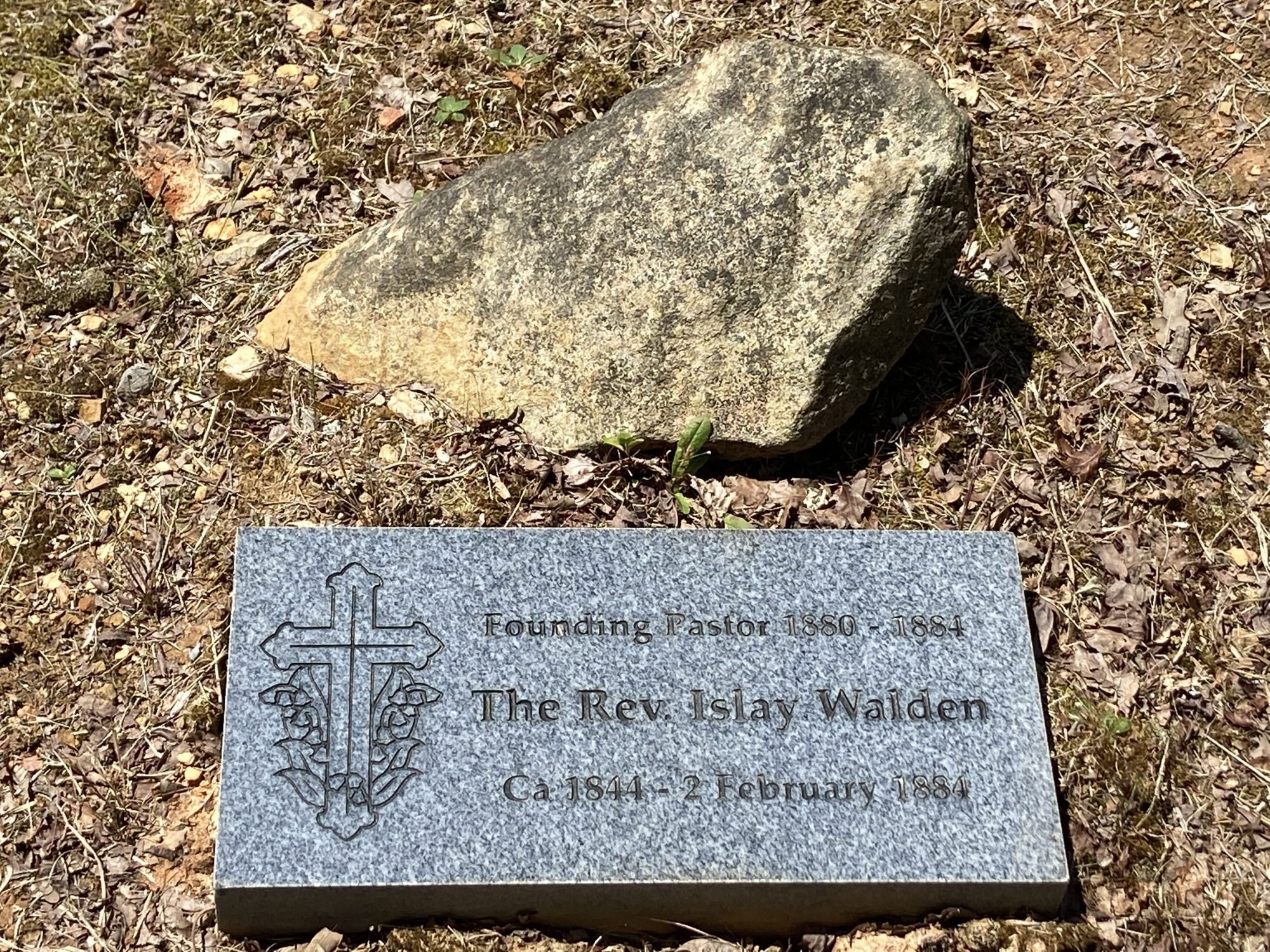

I’ve visited the grounds around Strieby Church, which was designated a Randolph County cultural heritage site in 2014, many times over the years. Set in a small clearing off a dead end road, the original church was replaced with a brick structure in 1972. A walkway between the building and the graveyard passes under the canopy of massive oaks with vibrant moss around their base. It’s an inspiring and peaceful place. I went again recently, after reading Williams’ book. The markers for Walden and his wife are modest – obviously placed many years after their passing – with humble inscriptions. Islay’s says Founding Pastor. Eleanora’s says Principal and Teacher. A field stone – perhaps the original marker – lies next to each one.

I paused there and thought of how much was encompassed in those brief descriptions. And how much more Walden might have accomplished if he’d been born a free man and had lived another 40 years. That’s the brilliance of Williams’ biography. She presents her meticulously researched details without embellishment or speculation, allowing readers the space to engage with her subject, eventually developing a connection with him.

While much of Walden’s story is specific to the Uwharries, it is also universal and deserves to be read by a wide audience. Those of us in this region – long overlooked in so many regards – are indebted to Margo Lee Williams for telling these stories.