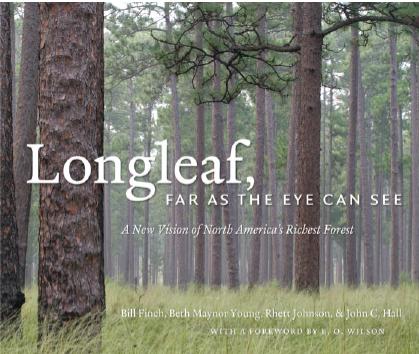

Longleaf, far as the eye can see

In Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest, Lawrence Earley traced the changes in society and technology that reduced a swath of forest once covering 92 million acres to isolated pockets totaling less than 3 million acres today. In telling the story of the longleaf, the former editor of Wildlife in North Carolina also told the story of the South. Many consider it the definitive history of the longleaf pine.

Now, nearly a decade later, Longleaf, Far as the Eye Can See has arrived with a fresh perspective on the topic. It’s a handsome volume, filled with page after page of glorious photographs, with an impressive foreword by eminent biologist E. O. Wilson. Primary author Bill Finch opens the book with a tale from the Piney Woods of eastern Mississippi. The story goes that a man who was eager to show off a fine pair of mules had them jump up on a longleaf stump then turned them in a perfect circle. What follows this memorable image is an impassioned and poetic ode to the longleaf ecosystem.

Now, nearly a decade later, Longleaf, Far as the Eye Can See has arrived with a fresh perspective on the topic. It’s a handsome volume, filled with page after page of glorious photographs, with an impressive foreword by eminent biologist E. O. Wilson. Primary author Bill Finch opens the book with a tale from the Piney Woods of eastern Mississippi. The story goes that a man who was eager to show off a fine pair of mules had them jump up on a longleaf stump then turned them in a perfect circle. What follows this memorable image is an impassioned and poetic ode to the longleaf ecosystem.

Finch brings an intimate knowledge to bear on his subject. “We never imagined in those days decades ago when we walked the longleaf hills in search of coveys to bring home for Thanksgiving dinner, how intricately the life and success of quail were tangled up in the wild meadows of grasses and wildflowers we trampled through, or the role those dark columns of longleaf played in assembling it all.” You can hear the wistful tone in his voice as he looks back on this innocent experience with an adult’s knowledge of what has been lost.

But Finch isn’t a hopeless romantic pining away, so to speak, for the past. He’s an optimistic pragmatist. He makes a compelling case that “the key to longleaf’s resurgence as a forest is its revival as a commodity.” While protected public lands have a role to play in restoring the longleaf ecosystem, so do private landowners. Those of us in timber management ought to consider planting trees that have the ability “to shrug off adversity.” Finch elaborates on this point by saying, “The threats that endanger so much of the South’s plantation forests – drought, fire, wind damage and insect attack – are the tools that longleaf has evolved to use to its own advantage.” If managed properly, a working longleaf forest offers other benefits as well. It will offer an abundance of wildlife for hunters and birders, and it will maintain its aesthetic appeal. This means “a working longleaf forest can still be a whole forest.” In fact, timber harvests can actually enhance them. “Longleaf is one of the few forests that allows us to have it both ways,” he says.

The Uwharries garner only a single mention in the book, but the section on Piedmont or montane longleaf applies to our region. Despite being on the edge of its range in areas like ours, “longleaf growing on piedmont clays may have produced some of the most impressive forests on the continent.” This assertion seems well-founded since the state champion longleaf is found on the eastern flank of the Uwharries near Ether. That tree is 106 feet tall with a circumference of 145 inches (See a photograph below).

In Looking for Longleaf, Lawrence Earley noted that Piedmont or montane longleaf communities are the rarest and least understood. Some answers might be coming to light at the Margaret J. Nichols Longleaf Pine Preserve. This 116-acre tract of old-growth trees north of Troy is likely the most important stand of Piedmont longleaf in the state. A grad student at UNC Greensboro recently cored 15 trees and found one to be 241 years old. Think of it – when that tree was a seedling, we were still an English colony. The largest tree, with a diameter at breast height of 32 inches, was only 84 years old. Many trees bear scars from turpentine production. Those trees have stories to tell. We expect them to share some of their secrets as fire is reintroduced to the stand. The first burn occurred this winter and more are planned for the coming years.

In Looking for Longleaf, Lawrence Earley noted that Piedmont or montane longleaf communities are the rarest and least understood. Some answers might be coming to light at the Margaret J. Nichols Longleaf Pine Preserve. This 116-acre tract of old-growth trees north of Troy is likely the most important stand of Piedmont longleaf in the state. A grad student at UNC Greensboro recently cored 15 trees and found one to be 241 years old. Think of it – when that tree was a seedling, we were still an English colony. The largest tree, with a diameter at breast height of 32 inches, was only 84 years old. Many trees bear scars from turpentine production. Those trees have stories to tell. We expect them to share some of their secrets as fire is reintroduced to the stand. The first burn occurred this winter and more are planned for the coming years.

For Finch, “The road through the range of longleaf is, for too many miles, a trail of tears.” Even though we’ll never experience the extensive longleaf forests that once occurred in our region, remnants like the Nichols tract are still important. They sustain a diverse suite of species, connect us with our natural and cultural history, and provide a glimpse of the longleaf forest’s appeal. They also show us the way forward, giving us a sense of what we’re aiming to restore.

To learn more about longleaf in the Piedmont, attend a presentation by Lawrence Earley on Friday, April 12 at 7 p.m. at the Montgomery County Cooperative Extension office, 203 W. Main St. in Troy, and participate in Nature Day activities at the Nichols Longleaf Pine Preserve on Saturday, April 13, 1-4 p.m., 3239 Highway 134, north of Troy.