With more deer but few predators, county turns to hunts

Mecklenburg County’s population of white-tailed deer has ballooned in recent years, as residents of Charlotte and other towns can verify with frequent sightings of deer gamboling and grazing in backyards, gardens, parks and greenways.

At the same time, deer hunting in North Carolina’s most urbanized county has also expanded, in part through specialized hunts. The Wildlife Resources Commission reports that 806 deer were reported killed in Mecklenburg during the 2015-2016 season, the most current figures available. That’s up from zero in 1980 and 266 in 1997.

The rising city deer population is just one example of the complexities of urbanized wildlife habitats. Without hunting or natural predators like wolves or cougars, and adaptable to urban conditions, deer can overpopulate in the city. That leads to health problems from lack of food, as well as mortality from collisions with vehicles – a danger to both deer and the occupants of the vehicles.

Deer tracks in the sand along McAlpine Greenway. Photo: Nancy Pierce

Deer tracks in the sand along McAlpine Greenway. Photo: Nancy Pierce

So while deer hunting may seem an anomaly in an urban setting of a million people, and it’s effectively banned in the city of Charlotte, it does take place – if under the radar – in the county, providing sport, meat for the table and population control for the deer.

Why does Mecklenburg have so many white-tails? The county Park and Recreation Department website traces the boom in deer, estimated at 8,000 to 24,000 animals, to several factors. The City of Charlotte bans shooting firearms and arrows, making the city a de facto sanctuary. The only major source of mortality for deer in most of the county is collisions with cars. In addition, many homeowners feed and protect deer.

(Today’s statewide deer population is estimated at 1.25 million compared to a historic low of 10,000 around 1900, according to the wildlife commission.)

In Mecklenburg, hunters can take deer during special hunts in Cowan’s Ford, Latta Plantation and McDowell nature preserves; during an Urban Archery Season in Huntersville and Pineville; and during the regular hunting season on private lands outside municipal limits.

Gary Marshall, natural resources coordinator for Mecklenburg Park and Recreation, said the hunts in the nature preserves keep deer numbers in check so they don’t over-browse the vegetated landscapes. “The reason we do this is population control,” he said. Hungry deer can blitz every green plant they can reach.

Culling excess deer – numbers that exceed the biological carrying capacity of the habitat – improves the health of the remaining herd.

Marshall said the hunts began after the county acquired Cowan’s Ford Wildlife Refuge in 1992 and officials saw the damage inflicted by over-abundant deer. He said the density was estimated at 150 deer per square mile, far too great for the 850-acre refuge.

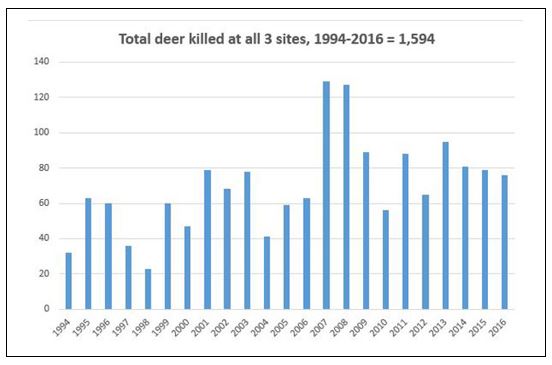

The first hunt took place in 1994, with Park and Recreation later opening Latta Plantation (1,464 acres) and McDowell (1,127 acres). Last November, hunters at the three park sites killed 76 deer, raising the overall 22-year total to 1,594. The Cowan’s Ford hunt embraces two smaller preserves, Rural Hill and Stephens Road.

Hunters are chosen by lottery. Hunts take place in two two-day periods: One for muzzle-loaders, the other for shotguns. No baiting is allowed. Not all preserves are hunted each year.

During the hunts, officials close the parks. They require hunters to wear blaze-orange hats and vests and allocate each person 20 acres in which to hunt. Marshall, who oversees the hunts, said some hunters even get their statewide annual limit of six deer. There are no quotas. He said no incidents or injuries have occurred during the hunts.

Objections are few, coming from park neighbors who don’t want to see animals they’re familiar with killed. “For the most part, people understand population control is necessary,” he said.

A bobcat and a deer, spotted on preserved land in north Mecklenburg County. Photo: Nancy Pierce

A bobcat and a deer, spotted on preserved land in north Mecklenburg County. Photo: Nancy Pierce

Hunters who don’t want to take their deer home for steaks and sausages donate the carcasses to Refugee Support Services in Charlotte, where they’re given to Montagnard refugee families who consider venison a delicacy and a “taste of home,” according to executive director Rachel Humphries. The Montagnard community began resettling in Charlotte from Vietnam in the 1980s. She said one deer can supply 10 families, and typically families share the meat with one another.

Humphries said the organization usually gets five to 10 deer from the hunts each year, as well as deer and game from other hunters.

Marshall said park officials continually assess the health of deer. Along with weight and age, they test the animals for parasite counts, an indicator of health. A high amount of stomach parasites indicates deer aren’t getting enough nutrition. A recent Park and Recreation handout describing the hunts noted that a 2013 study showed “that the herd is possibly near nutritional carrying capacity and that the deer generally are in poor to fair nutritional condition.” Marshall said he believes deer condition has improved since that study.

“Our goal is to maintain a carrying capacity of 40-50 deer per square mile,” he said.

Begun in 2007, the four-week Urban Archery Season is open to municipalities. The intent is to allow cities and towns to reduce urban deer populations. Among the municipalities in Mecklenburg County, Huntersville and Pineville have signed up. So have nearby towns in other counties, such as Concord, Belmont, Harrisburg, Indian Trail and Waxhaw.

A camera beside a Mecklenburg greenway captured this small herd of white-tailed deer one night. Photo: Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department

A camera beside a Mecklenburg greenway captured this small herd of white-tailed deer one night. Photo: Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department

Last year, of 59 N.C. towns with the archery-only hunts, Huntersville led the state with 17 deer harvested. Hunters in Pineville killed four. This year’s season ran Jan. 15-Feb. 18. Matthews isn’t part of the Urban Archery Season but issues permits for archery hunting within its limits. Chief Rob Hunter said by e-mail the town doesn’t track the number of deer taken.

In addition, legal hunting occurs on Mecklenburg’s privately owned forests and fields. That accounts for most of the reported harvest averaging 700-900 a year for the past 10 years. It may come as a surprise that the 2015-2016 Mecklenburg harvest was greater than that of 18 other counties, many of which are in the mountains where deer populations are relatively sparse.

Source: Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department

Rupert Medford, District 6 biologist for the wildlife commission, notes that Mecklenburg has high deer populations with little huntable land. A 2015 deer distribution map prepared by the wildlife commission show densities of 45 animals and more per square mile in non-urban areas along the Catawba River, in the northeastern tip and in the Mint Hill area. The same is true for much of Gaston and parts of Forsyth (Winston-Salem) and Wake (Raleigh) counties.

“The No. 1 place (in the district) where complaints come from is Mecklenburg,” Medford said, mostly of deer eating landscape plants. As herbivores, deer feed on many green-leaved succulent plants, new growths of stems, and fruits and acorns. Keeping deer out of yards is difficult. “The only sure deer barrier is a woven wire fence or brick wall 8-10 feet tall,” according to the wildlife commission. A Charlotte ordinance limits fence and wall heights to 5 feet, in some cases to 6 feet, except rear fences may be up to 8 feet, thus precluding wraparound deer barriers.

Mecklenburg County, much of which is layered with asphalt, concrete and lawns, provides less food than a rural county. As a result, Medford said, Charlotte deer are in poorer condition than deer herds that are hunted. “(Hunted deer are) healthier than their un-hunted counterparts,” he said. In response, under-nourished does often will give birth to one fawn rather than the usual twins or even skip the breeding season.

“Too many deer is not good for the deer,” he said, “and not good for the habitat.”

Brothers Alex, left, and Michael Castelli with deer they bow-hunted during the regular season in November 2016 in a rural area of Mecklenburg County near the Cabarrus County line. Hunting is allowed in unincorporated areas, and several municipalities near Charlotte allow bow-hunting during specified seasons. Photo: Courtesy Michael Castelli

Brothers Alex, left, and Michael Castelli with deer they bow-hunted during the regular season in November 2016 in a rural area of Mecklenburg County near the Cabarrus County line. Hunting is allowed in unincorporated areas, and several municipalities near Charlotte allow bow-hunting during specified seasons. Photo: Courtesy Michael Castelli

Jack Horan is a freelance writer specializing in outdoors, wildlife and conservation topics and is the retired outdoors editor of the Charlotte Observer.

Jack Horan