Musical heritage: Meet Earl Scruggs and Don Gibson

Earl Scruggs (1924-2012)

Earl Scruggs in 2005. Photo used under Creative Commons license.

He was 10 years old on the family farm in Flint Hill — about eight miles from the former county courthouse in Shelby that now bears his name — when Earl Scruggs and older brother Horace got into a “fuss.” After it was over, Earl shut himself in a bedroom to calm down and began picking “Lonesome Ruben” on his banjo.

The boy had played banjo in a family of musicians since he was 4, the same year his banjo-picking father, George Scruggs, died. Like his father, Earl always picked with a prodding, old-timey two-finger style. But on this day, still steaming from his fight with Horace, he realized he’d added a third digit to his picking — a technique using the thumb, index and middle finger that ultimately would become known as “the Scruggs style.”

“He jumped up and ran through the house to Horace shouting, ‘I’ve got it! I’ve got it!’” said nephew J.T. Scruggs of Boiling Springs. “For Earl, it was a breakthrough.”

Same’s true for the banjo.

Earl Scruggs didn’t invent the up-picking style. But he sure perfected and popularized it, removing the five-string banjo from the shadows of the rhythm section to an exuberantly out-front, solo instrument.

He practiced constantly, and in 1939, at 15, (a new book about Scruggs suggests the year may have been 1941) Scruggs began playing at dances with the Morris Brothers (George, Wiley and Zeke) from McDowell County. He quit performing during World War II and went to work at the Lily Mill, a yarn mill in Shelby, to support his mother and sister.

After the war, he returned to music, joining a group with a radio show on WNOX in Knoxville, Tenn. There he ran into fellow North Carolinian Jim Shumate, who played fiddle with the Blue Grass Boys led by Kentuckian Bill Monroe. When Monroe’s banjo player left, Shumate urged Scruggs to try out. Scruggs drove to Nashville and played for Monroe, who’d never heard a banjo played so furiously. Monroe hired him instantly and Scruggs was introduced to the Grand Ole Opry, J.T. Scruggs said.

As one of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, Scruggs became a part of the founding of a new genre of music called bluegrass. He had a title too: the father of the bluegrass banjo. Yet after two years of little pay and constant travel, Scruggs and guitar player Lester Flatt quit Monroe despite his pleading that they stay. Monroe was irate and didn’t talk to the duo for 20 years. He managed to get them banished from the Opry for two years.

But with their Foggy Mountain Boys, Scruggs and Flatt forged a musical partnership that would make them celebrities.

Two songs in particular brought them wide acclaim. “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” first recorded in 1949, played a prominent part in the 1967 movie “Bonnie and Clyde,” and “The Ballad of Jed Clampett” was the theme song to the 1960s TV show “The Beverly Hillbillies.” The pair appeared on the show many times.

Scruggs won four Grammys, and the National Medal of Arts in 1992. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In a tribute to Scruggs in The New Yorker magazine, actor/comedian Steve Martin (himself a talented banjo picker) wrote that Earl was the instrument’s most influential player:

“Few players have changed the way we hear an instrument the way Earl has, putting him in a category with Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, Chet Atkins and Jimi Hendrix.”

Don Gibson (1928-2003)

They called him “the Sad Poet,” so filled with heartache were many of the country music songs that Don Gibson wrote.

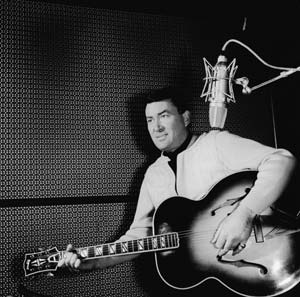

Don Gibson. Photo: Don Gibson Theatre.

He was born into a poor sharecropper family in Shelby, and took up the guitar as a teenager. In high school, he started performing in local clubs and after graduating, pursued music while working an assortment of jobs: jukebox repairs, delivering diapers, and washing dishes, according to his obituary on CMT (Country Music Television).com. In 1948, playing with the band The Sons of the Soil, he performed his way onto a local radio station, WHOS.

Four years later, at age 24, Gibson moved to Knoxville, Tenn., signing with RCA Victor and performing on the influential country music station, WNOX.

In Knoxville, he wrote three of country music’s most beloved songs that would become classic examples of the “Nashville sound.” The first, “Sweet Dreams” in 1956, became hits for Gibson (his version charted at No. 9) and Faron Young. The song became a wider hit when Patsy Cline’s version was released in summer 1963, months after the singer was killed in a plane crash. That cross-over hit rose to No. 5 on the country music charts and No. 44 on the pop music charts.

Gibson said he wrote the other two songs, “Oh Lonesome Me” and “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” in one afternoon in 1957 living in a Knoxville trailer park when “as he later said, he couldn’t have been any closer to the bottom,” wrote music historian Tony Russell in The Guardian, a British newspaper.

With those two songs, Gibson’s career soared. His 1957 recording of “Oh Lonesome Me” on a Chet Atkins-produced record topped the charts, and became a prototype of the “Nashville sound” championed by Atkins. The cross-over sound was a cleaner depiction that made country music more approachable for wider audiences by “removing the musical elements that seemed to stereotype it — primarily the fiddle and pedal steel guitar,” Russell wrote.

The Carolinas Urban-Rural ConnectionA special project from the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute |

|---|

They were replaced with more mainstream pop music instruments. As Russell wrote: “With its plaintive vocal framed by an inoffensive pop arrangement of piano, guitars, rhythm and backing singers, “Oh Lonesome Me” shed the homely garments of the genre and donned the bright new clothes of pop music.”

He became a member of the Grand Ole Opry in 1958, Russell wrote.

Gibson’s songs were recorded by hundreds of artists. More than 700 recorded “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” with Ray Charles turning the song into a No. 1 hit in 1962. Neil Young’s version of “Oh Lonesome Me” was one of the few songs Young recorded that he didn’t write.

Success brought problems; by the mid-1960s Gibson was struggling with prescribed diet pills and alcohol. He moved back to Shelby in 1967, where he met Bobbi Patterson, who became his second wife. She helped him kick his chemical dependency and the couple returned to Nashville, where Gibson continued to write and record into the 1970s. North Carolinian Ronnie Milsap’s recording of Gibson’s “(I’d Be) A Legend in My Time” was a chart-topper in 1974, as was Emmylou Harris’ version of “Sweet Dreams” a year later.

Gibson was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1973 and the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2001. He died two years later and is buried in Shelby’s Sunset Cemetery.

David Perlmutt