New toolkit lets you probe Charlotte history

Who used to live in your house? When was your neighborhood built? Was your subdivision legally segregated? How’d your street get its name?

Start wondering about where you live, and these kinds of questions are bound to crop up. And in a fast-changing, shiny “New South” city like Charlotte, it can seem like there isn’t real history, a concrete sense of place and identity, in many parts of town. A new website launched this spring hopes to change that.

The Charlotte Neighborhood History Toolkit, the brainchild of community historians Michael Moore and Tom Hanchett, is a central resource for people who want to explore the history all around them.

“I get calls like that all the time — how do you do this, how do I find out about this house?” said Moore, who moved to Charlotte about six years ago from New England. “People think I’m crazy when I say this, but I think Charlotte is a really good place to do history. There’s so much change. People are seeing it in real time.”

The toolkit, supported by a grant from the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, is free to use. It’s not a collection of all the resources, but more of a how-to guide, complete with links and detailed walk-throughs of how to use various sources.

Old newspaper archives, city directories, plat maps, deeds and building permits are scattered throughout a variety of websites in Charlotte. They can be challenging to find and navigate, but once you know how, they unlock a lot of stories about how neighborhoods came to be.

Even the most mundane-seeming records can reveal stories about what was built when, by whom, for whom — the building blocks of neighborhood history.

“Plat maps are fabulous,” said Moore. “I just love them.”

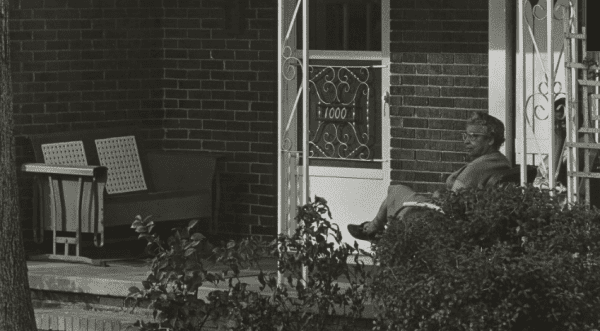

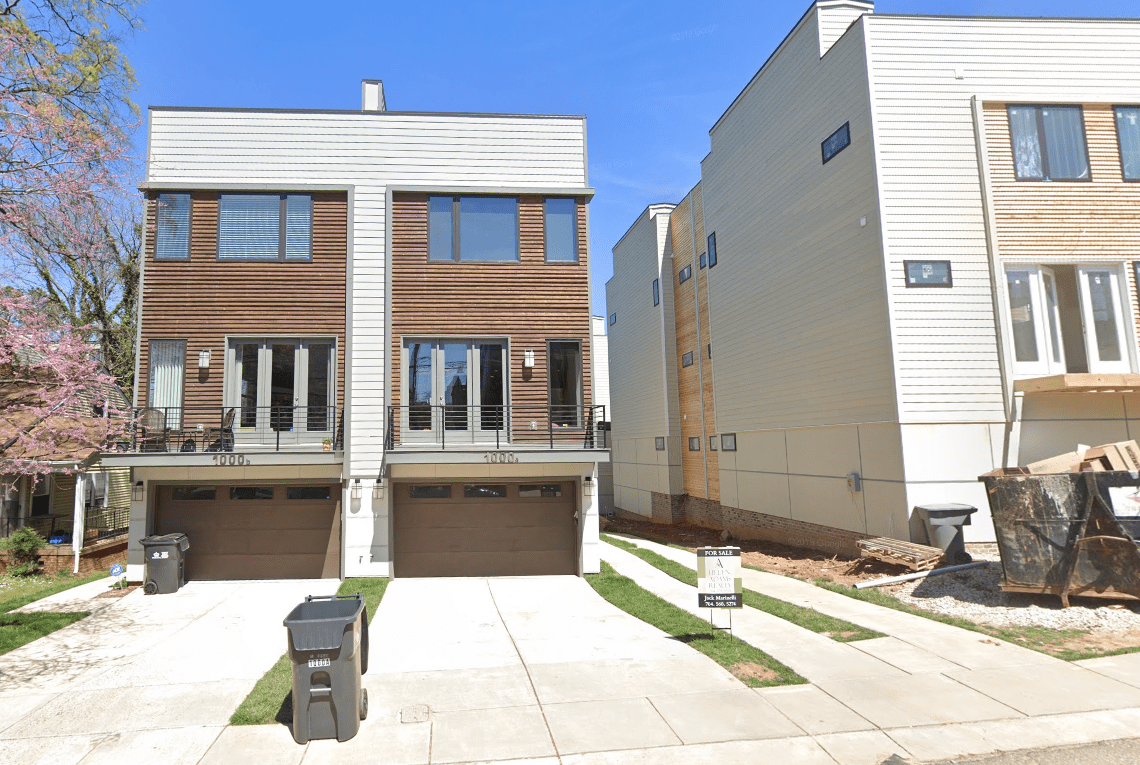

1000 Westbrook Drive today. Photo: Google Street View

Old city directories can tell you who used to live in your house. Newspaper archives contain original advertisements, like those for Oaklawn Park in the 1950s inviting “our colored citizens” to an open house in what was originally laid out as a neighborhood for African Americans.

“The goal is to make it really simple” for people to find and understand historical resources about their neighborhood, said Hanchett, the library’s first historian-in-residence. He’s found out some interesting details about his own house from city directories and old news clippings, such as that it was once partially rented to boarders and a former resident was busted for keeping exotic snakes there in the 1970s.

And the gains from understanding the history of a place go beyond the abstract: Hanchett pointed to Dilworth, which grew into one of the best-organized and strongest local neighborhoods, starting in the 1980s, with a group of residents coming together around the area’s historic past.

“A way for a neighborhood to build its own sense of community is to brag on its history,” said Hanchett. “It’s a process that brings people together if they know their history.”

Moore said he hopes the new toolkit will help people dismiss the notion of Charlotte as a city without history.

“Charlotte is just replete with stories,” said Moore. “Something has gone on here and is worth knowing about. It’s not just the story of a couple high rises downtown and some banks.”