In pursuit of a tiny bird in a big forest

I’ve spent the spring and early summer in pursuit of a tiny, black and yellow bird with a buzzy song – the black-throated green warbler of the Uwharrie National Forest. It’s made for an experience I’ll never forget.

As a Duke University graduate student, I’ve been an intern during May and June with the LandTrust for Central North Carolina, assisting John Gerwin, an ornithologist from the N.C. Museum of Nature Sciences, with his bird and vegetation surveys in the Uwharrie National Forest. It’s an experience I’ll remember for the rest of my life.

Our main object is the black-throated green warbler. We try to collect physiological and genetic data by catching, tagging, and releasing the birds. While we work, we look for birds captured in previous years and record information about their habitat.

The black-throated green warbler is a small songbird of the New World warbler group. Its black bib and bright yellow face are unique among birds of the eastern U.S. This bird can be recognized easily, not only by sight, but also by its sound, a song that sounds like “zee-zee-zee-zoo-zee” or “zoo-zee-zoo-zoo-zee”.

The warbler breeds in coniferous and mixed forest but occupies a wide range throughout its life. In August, it flies south from the northeastern U.S. and Canada to its Central American wintering grounds. But the warbler also nests in Virginia and parts of North Carolina. Our survey focuses on the black-throated green warblers found in the Uwharrie National Forest, which seems to be an isolated habitat for them.

The Uwharrie National Forest is primarily in Montgomery County, but extends into Randolph and Davidson counties in south central North Carolina. Most of the time, we are on Daniel Mountain or other mountains near it. According to former reports, the black-throated green warbler is usually heard on the northeast slopes of the mountains.

We begin our hike through the mountain trails at 7:30 a.m. daily, then head off the trail on a zigzag pattern through the terrain. When we hear the songs of black-throated green warbler, we stop at one spot and play a recording of the bird’s song. In general, the male bird will be attracted by this imaginary male’s song and will come close to find out who might be challenging him for his territory. If we find a male bird is interested in our fake song, we will hold a vertical net in the clearing and put a decoy model of a black-throated green warbler and audio player on the branch nearby. The male will try to flush the decoy bird and get tangled in the net. The process requires a lot of waiting, watching and luck.

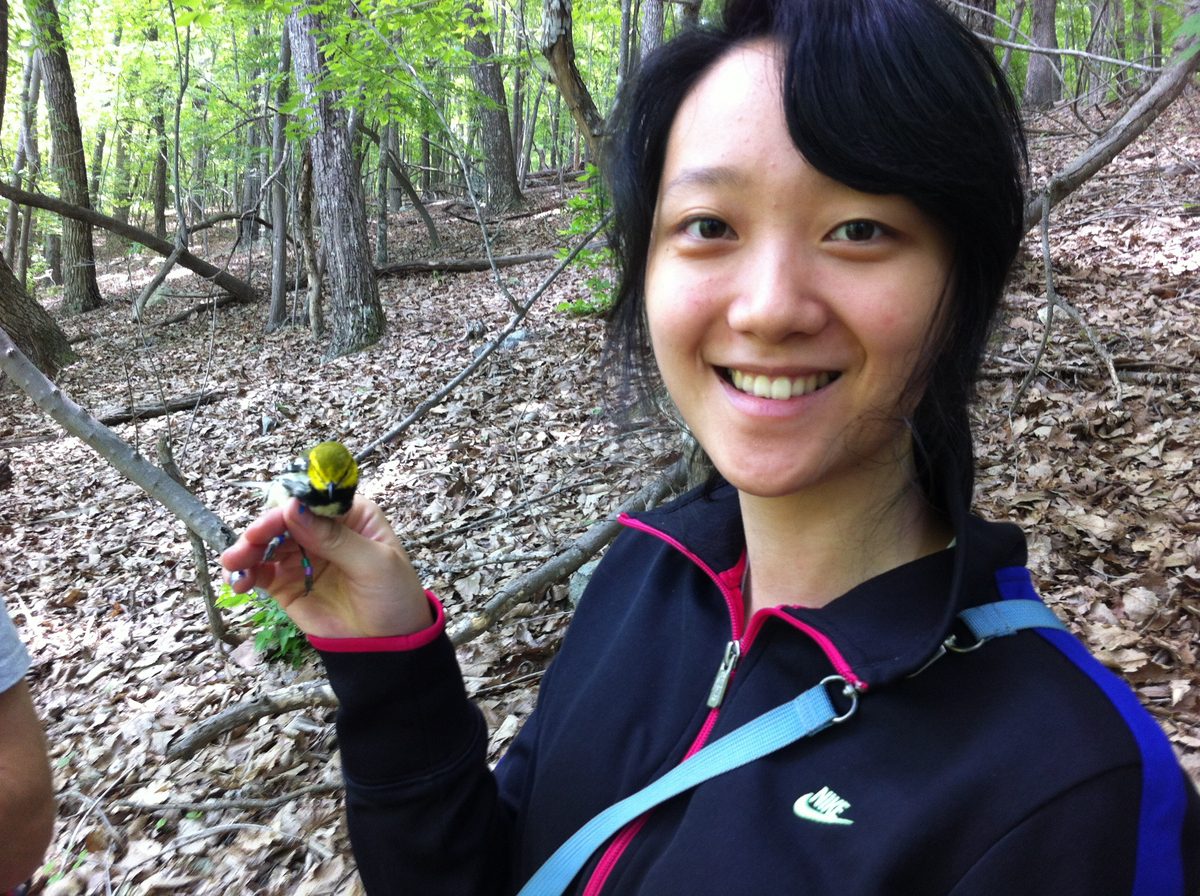

If we catch a bird, there’s a lot to do before he’s released. First, we put a small, numbered metal ring on the warbler’s feet to identify it. Then, using special measuring tools, we tally the bird’s wing length, weight and fat condition. During this process, we noticed that this year’s birds weigh about 8.5 grams, lighter than the typical weight of 9 grams. The drop in weight may signal that the birds have had a tough time at their wintering feeding grounds. I hope these lovely buddies can recover before migrating to the south.

Using a special needle, we draw blood from the tiny bird’s wing vein, an operation that doesn’t significantly hurt the bird. The blood sample allows us to collect genetic data on the animal.

For our next step, we will do some vegetation surveys to know more about the warblers’ Uwharrie habitat. The black-throated green warbler brings more vitality to the Uwharries, and I hope our efforts will help people understand more about the birds, so that we can live together with them long into the future.

Zoe Pu wrote this article while interning for the LandTrust for Central North Carolina in 2014. At the time she was a student at Duke University.

Zoe Pu