Saving Charlotte’s trees, one at a time

If trees could talk, what stories they’d tell. They’ve been silent witness to children shinnying up their branches and young lovers picnicking beneath their shade. They endure, watching over us from cradle to grave, and beyond. Charlotteans have a strong affinity with their trees, and for good reason.

The city has some 160,000 street trees, and approximately one public tree for every seven residents. Its overall urban tree canopy (which measures vegetative ground cover when viewed from above) is 46 percent, and an ordinance requiring tree planting and preservation aims to make that canopy a priority. However, a 2010 urban ecosystem analysis by the nonprofit conservation organization American Forests reported that between 1985 and 2008, Mecklenburg County lost 33 percent of its tree canopy and 3 percent of its open space, while gaining 60 percent of urban area. In the same time period, the City of Charlotte lost 49 percent of its tree canopy, 5 percent of its open space, and gained 39 percent of its urban area. (Click here for a PlanCharlotte article, “Group aims to restore shrinking city tree canopy.”)

The Charlotte area has a rich history of land planning, and its legacy has not been forgotten at Duke Mansion over the years. The mansion, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was nearly lost once to fire and later to development plans that would have converted it to condominiums. Its historic landscape is just as vulnerable. Recently, the Charlotte section of the North Carolina American Society of Landscape Architects met at the Duke Mansion to learn about its outstanding efforts to preserve its 4.5-acre, tree-studded setting.

“Often we think trees should live forever, but they need our help amid the pressures of urbanization and the turbulent forces of nature,” said Spence Rosenfeld, president of Arborguard Inc., an Atlanta-based firm whose Charlotte office is responsible for the health and preservation of the mansion’s historic landscape. “Trees provide shelter and beauty while bridging the gap in time between generations.” Rosenfeld and certified arborist Barry Gemberling led a tour of the mansion’s grounds.

Much of Charlotte’s tree-rich appearance flows from the hand of three important city planning firms. During the city’s early boom years of the 1910s to 1920s, the Olmsted Brothers, John Nolen, and Earle Sumner Draper all played a part in its beautiful neighborhood designs. Nolen brought Draper, a young landscape architect, to the Queen City in 1915 as field supervisor for one of its most historic neighborhoods, Myers Park. Here, Draper designed private landscapes and about one-third of the neighborhood layout, which he marked with grand, wide, curving boulevards.

Myers Park is also home to Duke Mansion, a classic example of Colonial Revival architecture built in 1915. Tobacco and electric power magnate James Buchanan Duke bought it for his family in 1919. It was later home to textile giants Martin Cannon and Henry and Clayton Lineberger of the Belmont textile family.

Draper, who had begun his own firm in 1917, was hired to design the original 15 acres surrounding the mansion, which Duke planned to triple in size.

Looking back some 65 years later, Draper described his planning aesthetic as being “of the old school, the Olmsted school,” as noted in an essay by historian Tom Hanchett of Levine Museum of the New South. Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. fathered a tradition of town planning in the late 1800s that responded to the topography of the land by using curved roads, rather than imposing a strict grid layout on a site that destroys its natural topography. Olmsted had begun using that approach in his design of New York’s Central Park.

At Duke Mansion, meticulous care is needed to tend the precious landscape left by Draper. The Arborguard staff uses a special soil therapy combining aeration and a custom mix of slow-release fertilizer and soil conditioners. Soil is inoculated with a mix of beneficial fungi, organic matter, sea kelp and other nutrients to simulate the decomposition that naturally occurs in forests.

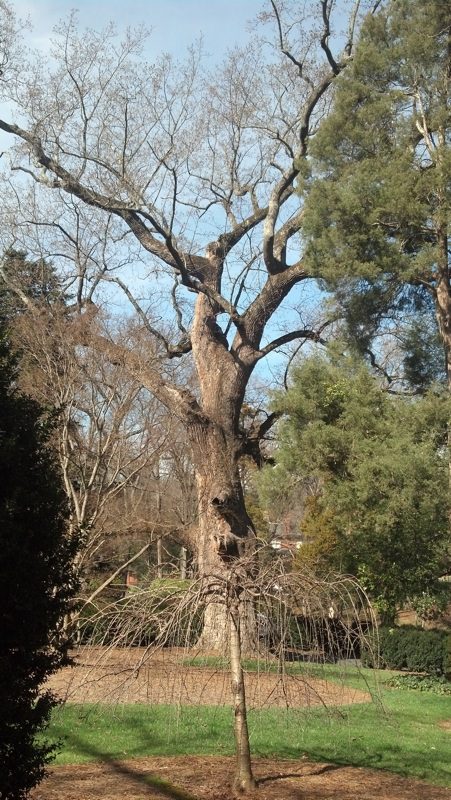

The special attention is worth it. The site contains hundreds of century-old, special trees, shrubs, and rows of boxwood.

The mansion is also home to five “Treasure Trees,” a designation given to 123 of the most outstanding tree specimens in Charlotte because of their age, size, or historical significance.

One such Treasure Tree is a 93-inch diameter poplar (measured at breast height, or 4-1/2 feet above ground), towering about 125 feet above the front yard along Hermitage Road. It’s the largest poplar in Mecklenburg County, with a majestic crown spanning another 125 feet.

Another of the mansion’s Treasure Trees is an Eastern red cedar that commands attention as you ascend the drive leading to the mansion. Its perfectly straight stature is estimated at 85 feet tall, with a 40-inch diameter.

Arborist Barry Gemberling also pointed out a grove of four, 45- to 50-foot high hemlocks near the left-front of the mansion. It is unusual to find hemlocks in southern areas like Charlotte; these evergreens typically live in cold climates and higher altitudes. The North American hemlocks have been devastated by the hemlock woolly adelgid, a sap-sucking insect that has caused extensive die-off, particularly east of the Appalachian Mountains. “So far, the small grove at Duke Mansion has shown no signs of adelgid infestation,” said Gemberling.

Duke Mansion has also been home to a bank training center, whose owners found it necessary to expand its parking. A lawn area near the driveway and mansion’s front entrance was chosen.

A logical location, but one also bordered by four historic specimen trees – two white oaks, a Southern red oak and a winged elm – each with diameters ranging from 40-45 inches and standing 85 to 90 feet high. Tree roots lie just inches below ground and extend many yards in all directions, making them vulnerable to injury by excavation and the compaction caused by heavy equipment.

The solution devised eliminated all excavation, instead placing the parking lot at grade over a layer of lightweight aggregate. Resting on this base, tree roots were bridged with no surface disturbance. The project was completed more than a decade ago, and today the trees remain healthy and unharmed, preserved in a slim, 8-foot wide strip between the driveway and parking lot.

Charlotte’s Treasure Tree program, originally started by a group of local arborists and volunteers, is no longer active. But, the city’s tree ordinance protects local “heritage” and “specimen” trees. Heritage trees are classified using the same criteria that originally applied to Treasure Trees – a listing on the state or national Big (Champion) Trees List, or any tree that meets 80 percent of the point-score of the listed champion. Specimen trees are those noteworthy examples of 24 inches or larger for hardwoods or softwoods (like poplar or pine), and 10 inches or larger for understory trees (like dogwood or redbud).

A beautiful Vitex agnus-castus (also known as a chaste tree), planted in the 1930s at the Wing Haven Gardens and Bird Sanctuary elsewhere in Myers Park, is both a Treasure Tree and a national champion. It is Mecklenburg’s only entry on the American Forest Association’s list of national champion trees.

Ian McHarg, in his Design with Nature, said that we are the “stewards of the biosphere. It is not a choice of either the city or the countryside,” he wrote. “Both are essential; but today it is nature, beleaguered in the country, too scarce in the city which has become precious.” Preserving a city’s landscape happens deliberately, one tree at a time. Like a queen without her crown, what would Charlotte be without its trees?

Opinions in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.