Slow Birding

Even casual birders feel the urge of spring migration. Within a few short weeks, millions of birds will pass through our forests, parks and yards. Many pause here only briefly to fuel up for their journey north, so this will be our only opportunity to get a glimpse of them in their breeding plumage.

We rush around to various habitats – riparian, grassland, upland forest – in an effort to see as many as possible. We lift our binoculars to the canopy and see a flash of yellow. It could be any number of warblers. We focus long enough to (hopefully) get a positive identification, and then we quickly move on. Other species might be flitting about in a nearby tree, and they might not be here long. It’s exhilarating, but it can also be exhausting and somewhat superficial.

Some birders essentially maintain this pace all year. They are the ones who might attempt a Big Year. The ones who fly to exotic international locations to add a few more species to their life list. They are accomplished, and sometimes intimidating. They can leave birders like me feeling a bit inadequate. My identifications are shaky. My binoculars are mediocre. My life list is short. My facility with eBird is limited.

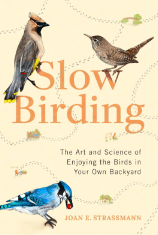

No one should be deterred from appreciating birds, no matter their skill, or resources, or dedication. Thankfully, Joan Strassmann is here to help. Her book Slow Birding: The Art and Science of Enjoying the Birds in Your Own Backyard reassures and empowers those of us who might feel marginalized by the birding elite.

No one should be deterred from appreciating birds, no matter their skill, or resources, or dedication. Thankfully, Joan Strassmann is here to help. Her book Slow Birding: The Art and Science of Enjoying the Birds in Your Own Backyard reassures and empowers those of us who might feel marginalized by the birding elite.

The title comes from the Slow Food movement which stresses local, seasonal ingredients and recipes. Strassmann realized the same concept could be applied to birding. She equates “motor birding” – racing around to pick up as many species as possible – to eating fast food. She advocates staying close to home and appreciating “the birds that intersect with our lives.”

When she was a professor at Rice University, Strassmann chose three common species around campus and asked her students to observe each one for at least an hour then “write about how each species used time and space and how it differed between the sexes.” She hoped the assignment would not only help students appreciate the birds themselves, but also help them “begin to understand the biological underpinnings of bird behavior.”

“A force in us drives us to the untamed,” she writes. “We dream of the wild, not the domestic, for it is wildness that is unknown.” In our daily lives, “birds are our closest connection with wildness.” While Strassmann appreciates the importance of keeping a list of birds you see, especially on platforms such as eBird, which makes the data available for scientific study, she urges readers to also follow the advice of ornithologist Margaret Morse Nice – sit still and watch.

To give readers a sense of the potential rewards, Strassmann does a deep dive on 16 common species around her home in St. Louis. “Each bird has a story, and a question to be answered,” she says. Many of these species will be familiar to those of us in the Piedmont – blue jays, cardinals, mockingbirds and wrens.

She also includes chapters on some of her favorite locations because “slow Birding is also about place.” She starts with her own yard, then expands outward to sites within a 20-mile radius of her house – a somewhat sterile 6-acre park in her neighborhood, a 1,300-acre park near downtown St. Louis that supports 220 species, a larger research center, and parks along the Mississippi River.

John Gerwin, research curator of ornithology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences has studied painted buntings at the North Carolina coast, Swainson’s warblers in the swamps of South Carolina and golden-winged warblers in Nicaragua, yet he still finds the common birds in his own backyard endlessly fascinating. The robins who’ve learned there’s an abundance of worms in the debris underneath his seed feeders. The Carolina wrens who sometimes slip into his home through an open window and search his corners for tiny spiders.

“Everyone used to want to do studies in wild areas,” he said. “But the logistics are hard. And wilderness is disappearing.” Sit with that for a moment. To remain relevant, researchers also need to focus on urbanizing areas like the Piedmont. While many species suffer from habitat loss, some are apparently better equipped than others to co-exist in our built environment. Cardinals, for example, seem to do better in cities, where there’s more “edge” habitat and less predation.

Gerwin notes that we’re gleaning insights through Neighborhood Nestwatch (About Neighborhood Nestwatch | Smithsonian’s National Zoo (si.edu)), a program based at the Smithsonian Institution that studies “the effects of rapid development on wildlife, while also educating citizens about the scientific process and human impact on wildlife.” Gerwin helped Raleigh become one of seven host cities across the nation. The focal list of species includes many of those covered in Strassmann’s book.