Students rethink how and what we memorialize

“Not many events inspire our historical imagination and force us to critically think about our past the way a falling monument does.”

Associate Professor of Sculpture Marek Ranis, who grew up behind the Iron Curtain in communist Poland, has seen monuments go up and come down in countries like his homeland. But the intense evaluation of monuments in the United States – what they tell us about our past and our present – and the determination to change how and what we memorialize is new to contemporary Americans.

“Our personal connection to most of such entities is rather vague,” he says. “It is a landmark, a monumental object, which most likely had been erected before we were born and will remain long after our death. We have been hardly noticing the men on horses we might be passing by daily.”

The current national focus (the Mellon Foundation recently pledged $250 million to efforts to create new monuments and rethink or relocate existing ones) and the global movement to question colonial history prompted Ranis to challenge students in his Topics in Sculpture for Architecture seminar to ask, “What is the role of contemporary artists, architects, and creatives in addressing these issues? What are the new, just, meaningful, and sensitive ways to be part of this cultural revolution?”

The architecture students – four undergraduates and three graduate students – each chose a monument, identified and researched issues associated with it, and proposed a design solution to those issues. Their projects tackled sites near and far.

Anna Hair and Justin Martinez, who are both completing Bachelor of Architecture degrees, chose sites in the countries of their birth. Hair, who moved to the U.S. from Ukraine in 2007, proposed a new sculpture to be erected in Kiev, across the Dnieper River from the “Motherland Monument,” a memorial from 1981 that carries associations with Soviet history. While “Mother Motherland” carries a sword in one fist and a shield in the other, Hair’s proposed sculpture is a large open hand, inspiring visitors to “reflect on the transition that Ukraine made from its communist days to their now independence” she writes.

Martinez, who came to Charlotte from his native Guatemala at the age of 19, seeks to redress the looting of ancient Mayan monuments and artifacts, which ended up in museums throughout Europe and the U.S. His “Tikal Futura” houses replicas of the displaced artifacts within a large building complex that includes a hotel, shopping, and other amenities to attract visitors. “The hope of raising awareness about these stolen objects from Guatemalan heritage is an attempt to create a foundation to fund the return of such objects to their rightful place,” he writes.

Elijah Willis and Rebecca Seagondollar, also undergraduate students, chose to consider regional monuments: Willis, the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C., and Seagondollar, the monument to Confederate politician George Davis in Wilmington, N.C. Both have made news in recent months, with debates over whether to remove the memorial in Washington and the decision to remove the statue in Wilmington.

Willis proposes to fulfill a wish made by Frederick Douglass for “a monument representing the Negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-foot animal, but erect on his feet like a man.” His project calls for a reorientation of the existing sculpture that allows the kneeling freed slave to look towards the center of Lincoln Park at a new sculpture of a Black man standing upright.

“This statue is meant to represent how the struggle is not over yet just because slavery ended. However, the Black man remains resilient in the face of adversity. He is smiling because he is hopeful and optimistic of the future.”

Seagondollar would begin by melting the bronze body of George Davis to make markers that would recognize the Wilmington Massacre of 1898. The plate on the monument’s base would be replaced with a panel that displays a map of the new markers’ locations. At those locations, new memorials would be placed – spherical-shaped benches that are engraved with historical information about those who lost their lives in the massacre.

Graduate students Keely Haggar and Trevor Vannucci turned their attention to the intersection of Trade and Tryon streets, Charlotte’s Independence Square, to render it more reflective of a complete and truthful local history.

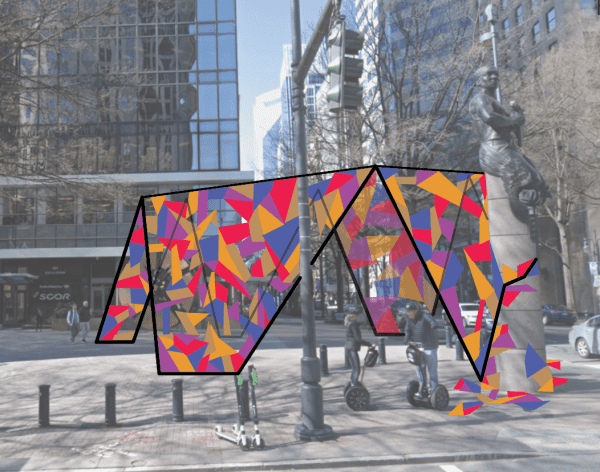

Keely Hagar saw the need for the four sculptures on the street corners to more fully represent the contributions of the Catawba and African American people. Her proposal is an installation inspired by African American “Freedom Quilts” that attaches to the “Transportation” sculpture (a Black man) and creates a canopy “quilt,” each piece of which contains an image, story, or fact about Native American or African American history.

Trevor Vannucci’s project focuses directly on the intersection of the two historic trails: The Great Warrior Path (which became the Great Wagon Road) and the Great Trade Path, both of which were forged by Native Americans and then used by settlers. Vannucci writes that the four monuments on the square “deliver nothing about the rich history of the site as a meeting place of two nation-wide paths which have served as the lifeblood of settlements here for hundreds of years.” He proposes a monument embedded in the roads, consisting of 4” wide brass inlays laid into the center of the intersection. He describes:

“These inlays will depict a scaled image of the two historic paths, and striking out from the intersection in all four directions these inlays will continue along the present day roads of Trade and Tryon for as long as they intersect with the historic routes. At the northern and southern terminus of these inlays, a steel plate will rise out of the ground with a thickened, perspectival window set into it which looks towards the continuation of the historic routes. As curious explorers find their way to the end of the path of this new monument, they will be presented with an opportunity to look through this window into the past and reminisce on the importance of these two historic roads, and all of the lives that have traveled along them.”

Rather than choosing a single site, graduate student Tyler Trudeau designed a mobile installation that, he describes, “can be placed at nearly any site within any context.” Modeled on shipping containers, the multiple units can be configured and programmed according to the space and its story.

“The installation is highly interactive and highly technological, utilizing augmented reality technology to display select images and distort the public space around the monument. Within the structure, a gallery of projected light and images fills the dark space, spelling the experiences of those who have faced injustice across the world.”

Meg Whalen