Surveys, Counts and Blitzes

Concerns about an “insect apocalypse” have grown more widespread in recent years. There’s a sense among scientists – and the general public – that we simply aren’t seeing as many insects as we used to. I remember driving through the Uwharries on summer nights when insects splattered the windshield like the first fat drops of rain from a sudden thunderstorm. In fact, scientists refer to this sense that something just isn’t right in the insect world as the “windshield phenomenon.”

But science relies on hard data, not on vague recollections. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to track insect decline because in most cases we don’t even have solid baseline data on their populations. Biologists lack the resources to do adequate amounts of field work, but they’re now finding ways to capitalize on the contributions of citizen scientists. This summer, people from across the state will have new opportunities to collect information and share observations of bees and other pollinators.

The most casual way to participate is through a project on iNaturalist. The Pollinator Bioblitz occurred during National Pollinator Week, which was June 19-25 this year. That week brought some much-needed rain to the Piedmont, but the cool, damp weather wasn’t ideal for pollinator activity. While it isn’t specific to insects, the North Carolina Summer Biodiversity Project (NCWF Hosting iNaturalist Bioblitz to Showcase NC’s Biodiversity During the Summer Season – North Carolina Wildlife Federation), hosted by the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, runs through September 23rd. All you have to do is upload photos and try to identify the species based on AI-generated suggestions. An expert will sometimes be able to confirm your sightings. I’m already hooked on iNaturalist, so these projects don’t entail any additional effort for me.

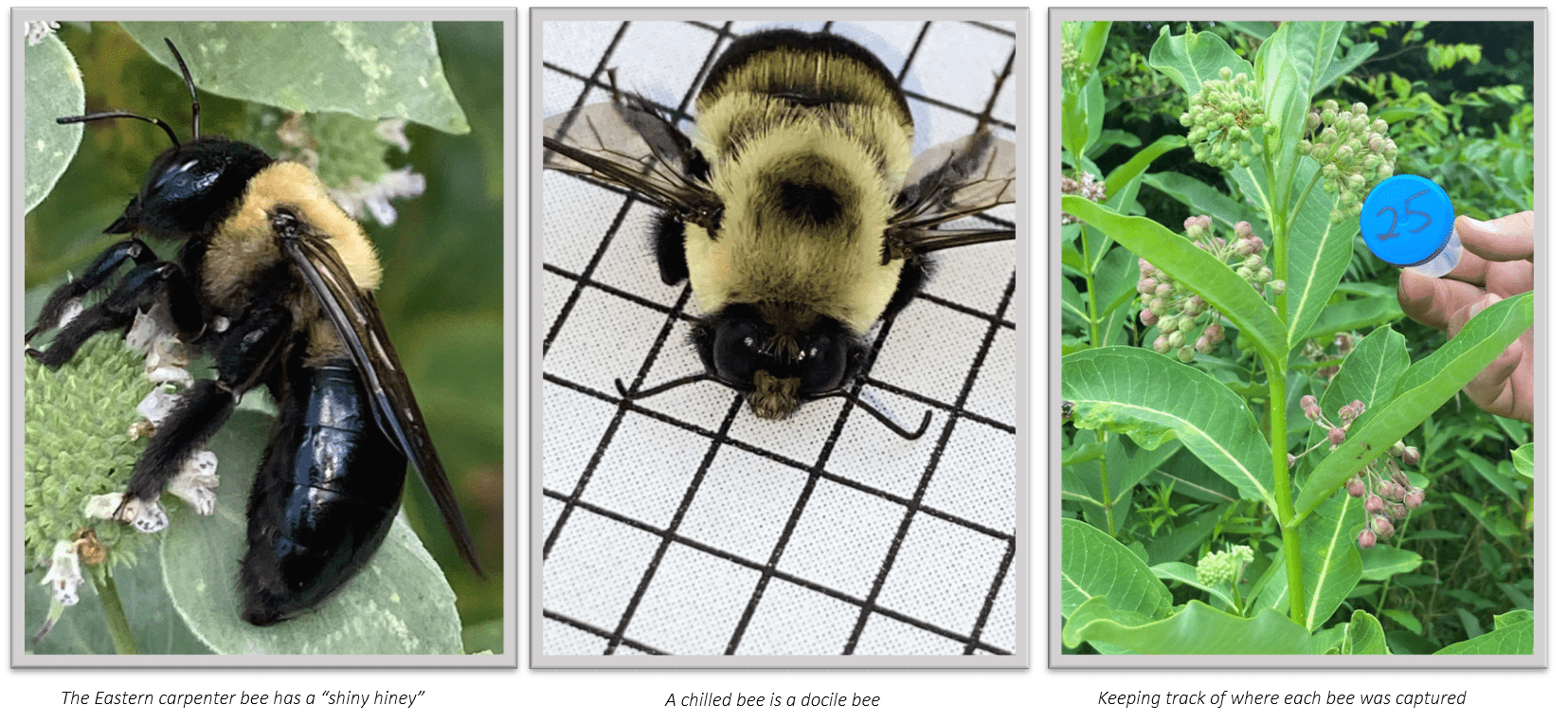

The Southeast Bumble Bee Atlas (Southeast Bumble Bee Atlas) is far more scientific. The Xerces Society has been spearheading this type of research in other regions of the country for many years, but it’s new to the Southeast. Here, they’re partnering with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC). Volunteers adopt a specific location and conduct two 45-minute surveys over the course of the summer. This includes netting bees, transferring them into vials, then chilling them in coolers until they’re docile enough to handle and photograph. Once the bees warm up, they’re released into the area where they were captured.

I’m quite comfortable around bees – I enjoy photographing them in my backyard – but after watching the training video on the website, I was a little intimidated by the protocols. Fortunately, I was able to survey a stand of common milkweed in the Uwharries with Gabriela Garrison, eastern Piedmont habitat conservation coordinator with NCWRC, who is helping launch the Southeast Bumble Bee Atlas. With her guidance, I now feel better prepared to participate in additional surveys in the Uwharries and perhaps even conduct one in my backyard or neighborhood park in Charlotte.

This multi-year effort will provide solid information about species distribution, population shifts and habitat associations. The data can be used to guide conservation by highlighting areas that are a priority for preservation as well as identifying those that could benefit from additional management or restoration.

The Great Southeast Pollinator Census (www.gsepc.org) seems to hit the sweet spot between casual and scientific. This two-day event originated in Georgia in 2017 and expanded into South Carolina in 2022. This year, it’s scheduled for August 18-19 and will include North Carolina for the first time. Amanda Wilkins, a horticulture agent at the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Office in Lee County, is helping with the statewide rollout of this project.

To participate in the census, simply choose a plant with a lot of insect activity – maybe a goldenrod or mountain mint or Joe Pye weed – then watch it for 15 minutes and record every pollinator that visits it during that time. Instead of asking participants to identify each species, which would be difficult for most citizen scientists, the census provides eight general categories – carpenter bees, bumble bees, honey bees, small bees, wasps, flies, butterflies/moths, and other insects such as ants or beetles. A training video on the website provides simple – and sometimes entertaining – tips for identification. I’ll never look at a carpenter bee again without thinking “shiny hiney.” This is great information even if you don’t plan to participate in the census.

To make the census even more fun, organizers suggest working in pairs, with one person observing and another person recording the observations on a data sheet. Larger groups can work together to quickly survey an entire pollinator garden. Project coordinator Becky Griffin at the University of Georgia Extension started the census in response to her work with community and school gardens. Even though the dates of the official census fall outside the school calendar, the project includes a strong STEAM component, with suggested activities for teachers (Resources for Educators – The Great Southeast Pollinator Census (gsepc.org)).

The data collected through all these projects will no doubt be helpful for scientists and conservationists, but these efforts will also have other direct benefits. Griffin noted that after participating in the census, gardeners have a new appreciation for the connection between their plants and the insects they support. The census has also inspired communities to create new pollinator gardens. This combination of awareness and action is the basis for protecting and improving habitat, which supports everyone’s ultimate goal – saving our imperiled pollinators.

To learn more about participating in the Great Southeast Pollinator Census, sign-up for this FREE webinar on August 10, 1-3p.m. Knowledge is Pollinator Power: A Census Pep-Rally!