Too much of a good thing: Bunny boom

No spiderworts. No asters. No threadleaf ironweed or liatris. Very few brown-eyed Susans and even fewer green beans. That was the sorry state of my garden last year. No, it wasn’t weather-related, it was rabbit predation.

My neighbor and I noticed a rabbit hanging around our yards last winter. One of its back legs was lame. Given all the red tailed hawks and barred owls in the neighborhood – not to mention coyotes and cars – we assumed it wouldn’t be around long. We actually felt sorry for it.

At least until the hordes of hungry bunnies started feasting on our gardens. Rabbits are common in our urban neighborhood, but we’d never seen anything like this. In a matter of months, she produced multiple litters, each one greedier than the last. In addition

to eating my vegetables and perennials, they chewed some of my young shrubs down to nubs. This was especially vexing because they didn’t actually consume the shrubs – they simply nipped the tender stems and left them next to the plant. Sheer meanness! Rabbits have both upper and lower incisors, so their cuts are as clean and efficient as a pruning tool. They killed the zenobia outright, and the New Jersey tea is struggling.

They also knocked back all five blueberry bushes and a couple fothergilla. I’m glad to support a sustainable number of rabbits in my yard, but last year they had an outsized impact, affecting the habitat I’m trying to provide for other critters, including imperiledpollinators such as American bumblebees and monarch butterflies. Not to mention robbing me of fresh green beans!

It was maddening. My neighbor and I were on high alert, exchanging outraged texts. The devils just ate a lobelia! There are two in my vegetable plot! My dogs just chased one into your yard! She even snapped a photo of the mama nursing one of her babies. It would’ve been sorta sweet if they weren’t being such a nuisance. After a while, we’d had enough. Full disclosure – we set up a Havahart trap. In what turned out to be a blessing in disguise – more about that in a moment – we never caught one.

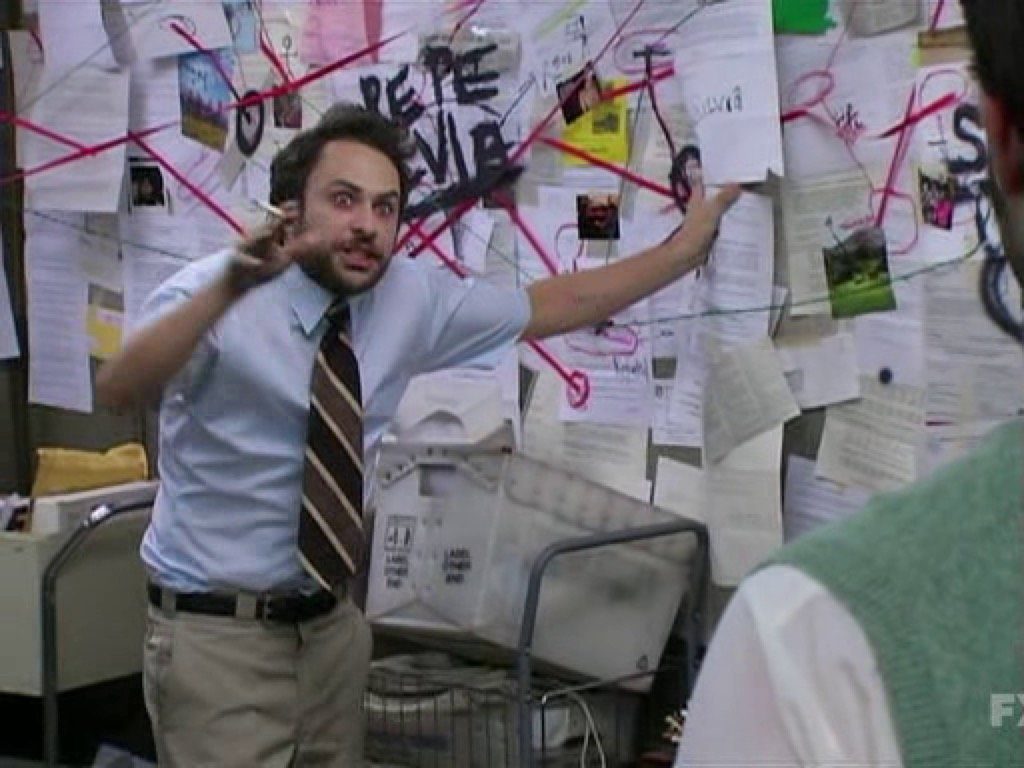

The offending rabbit suckling her young. Photo courtesy Ruth Ann Grissom

Why would they risk going into a sketchy metal cage for a paltry apple slice or lettuce leaf when they had a smorgasbord of fresh plants at their disposal? Exasperated, my only hope was that we might be experiencing the peak of a cyclical boom and their numbers would eventually dwindle. Was this just desperate, wishful, magical thinking?

For answers, I reached out to Andrea Shipley, a mammalogist with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. Shipley confirmed that Eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) populations do indeed experience significant fluctuations, generally on a four-year cycle. Reports from across the state indicated 2021 had been a boom year.

“What you’ve heard about rabbits is true,” she said. “They’re prolific breeders.” They can produce seven litters per year with as many as five to six per clutch. A female born in early spring can start reproducing by fall. No wonder we were having problems in our gardens! That said, rabbits in the wild generally live for less than three years, and their annual mortality rate can approach 80-90%. Populations build and decline over time due to several factors – disease, competition for food and cover, predation, vehicle strikes or changes in available habitat due to development or land management.

Shipley also gave me some sobering news – we weren’t allowed to blithely trap a rabbit and relocate it to a more hospitable location, say our local greenway. Even if we secured the required hunting license to trap during open season (which runs from mid-October through February) or a depredation permit, it’s illegal to release a rabbit on public land without written approval from the official authorized to manage the property. They can be released on private tracts with a landowner’s permission, but even that is discouraged.

Shipley said NCWRC recommends euthanizing a trapped rabbit as quickly and humanely as possible. That’s the protocol for critter control professionals. It sounded harsh, but her rationale made sense. Relocated rabbits probably won’t fare well. Their homing instinct would put them at risk for injury, starvation and vehicular strikes. Suitable habitat might already be supporting the maximum number of rabbits. They could also introduce disease to an otherwise healthy population. I’m not inclined to kill a rabbit and dress it for dinner, and I’m now reluctant to relocate a Charlotte rabbit to our property in the Uwharries, so in the end, trapping probably isn’t an option for us.

That leaves me with trying to limit their impact. Several sources recommend habitat modifications such as removing brush piles and “weedy” patches, but I’m not willing to do that – they provide necessary cover and sustenance for countless other species. I might step up

exclusion efforts, for example, putting a wire mesh cage around vulnerable young shrubs. I also hope my garden has another three years to recover before the local rabbit population booms again.