Transit station futures: Gloomy or bright?

Is it prescient and forward-thinking for the city to encourage subsidized housing at rapid transit stations in coming decades? Or would that be the nail in the coffin, killing any near-term chance to halt a pattern of sinking property values near some of those stations, especially in troubled parts of east and northeast Charlotte?

Two different visions of the future emerged Wednesday at a Charlotte City Council committee meeting. Committee members were discussing a proposed policy that aims to both encourage and limit subsidized housing near transit stations. One vision was articulated by City Council member Michael Barnes, who represents District 4, which includes the UNC Charlotte area and a big chunk of the route of the still-unbuilt Blue Line Extension.

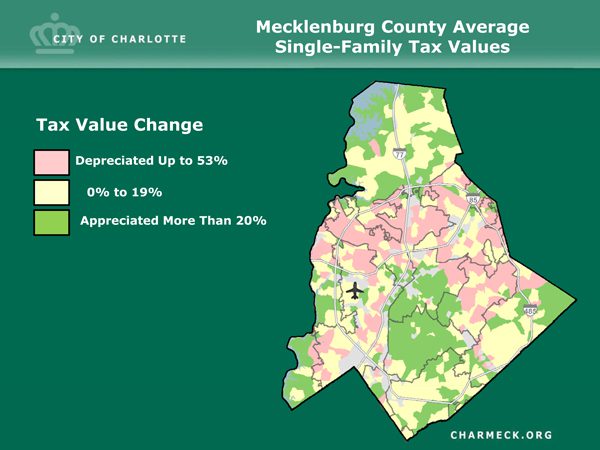

Barnes’ view, in a nutshell, is that in an area with plenty of inexpensive housing already and where property values are going down (see maps below), to encourage developers to include too much subsidized housing at transit station areas would seal the fate of the whole area as one troubled by all the problems that come with concentrations of low-income residents in low-income clusters.

On the other side were Charlotte Planning Director Debra Campbell and Neighborhood and Business Services department head Patrick Mumford, a former City Council member. They countered that nationwide, new light rail stations have proved such a powerful lure that property values rise, putting station areas out of reach for low-income families. That’s why the city needs a policy to ensure the presence of housing for low-income families near transit lines, they said. Think long-term, they added.

The proposal on the agenda was a policy for assisted multifamily housing at transit station areas. The Housing and Neighborhood Development Committee voted 3-1 (Warren Cooksey voted no; LaWana Mayfield was absent) to recommend the policy to the full council, which is expected to hear public comments April 23, and to vote May 14.

The policy would apply only to “assisted” units – units built with tax credits for affordable housing and reserved for households making only 60 percent or less of the area median income – and only within a half-mile of proposed and existing station areas. In other areas the city’s policies for the location of subsidized affordable housing would come into play. The proposed transit station area policy would require, for instance, that the subsidized units be part of a mixed-income project, with a minimum of 5 percent and a maximum of 20 percent of the total units being subsidized. The assisted units would be required to look similar to all the other units, and must be scattered throughout the development.

The provision that prompted much of the discussion – and which the committee recommended be removed – would have allowed one building in any project to be 100 percent assisted units.

Barnes rejected that notion. His concern: By concentrating low-income households into one building, you’d lower the value and the potential rents of all the surrounding buildings, and thus the whole project. “How,” he asked, “do we build value along the lines and grow our tax base?” He predicted that developers would see “free government money” and would take advantage and “do it in ways that will be completely detrimental to the Blue Line.”

To allow subsidized units to be concentrated in one building would doom the area surrounding the Blue Line stations, he said. “You’re literally putting a bullet through the head of the light rail lines, and you’re also wasting my time – all the time I’ve spent lobbying for the money [for transit].”

But, said Mumford, the extension of the Blue Line is the value that will be built. Market-rate housing will come, he said. “The transit line is going to entice good quality development.”

Barnes is sensible to be worried about too much low-income housing being too concentrated in an area that has seen virtually no middle- to upper-income housing in recent years. The maps showing property values sinking in much of the city – which were shown to council members at their recent retreat – are eye-opening.

On the other hand, since transportation typically is the second biggest piece of a U.S. household’s expenses, does it make sense to ignore other cities’ experience and sit by as rising property values wind up excluding the households that could benefit most from walkable access to public transportation?

Several closing thoughts: In its count of the housing units and assisted housing units already within proposed rapid transit station areas (that is, not counting streetcar routes), the city staff counted only “assisted” units, including Section 8 housing. They found that only 6 percent of the total housing units within a half-mile of current and proposed stations were subsidized units – the housing type the policy would address. Within a quarter mile of proposed stations, only 7 percent were assisted units. Looking at the quarter-mile zones, in only two stations (Ninth Street and Seventh Street) were more than 15 percent of the total units “assisted.” Looking at the half-mile zone, only two stations (25th Street and the New Bern station) topped the 15 percent mark.

By that measure, concerns may be overblown.

Yet the analysis didn’t count the larger problems of deteriorating housing, sinking values or the ripples of lost value from excessive foreclosures. Those issues plague big parts of northeast, northwest, east and west Charlotte. The analysis looked only within a half-mile around the proposed station areas. In a low-density city, with many proposed stations on wide highway rights-of-way (examples: North Tryon Street, Independence Boulevard) a quarter- or even a half-mile radius won’t capture many units, or much of the flavor of the surrounding area.

At the meeting, staff did not explain, and council members didn’t ask, why a one-size-fits-all policy was the right approach instead of a more fine-grained one that could take into account different situations in different parts of the city.

In the end, of course, there is no way to know which vision will come to pass. Light rail transit, in other cities, has pulled in high-quality and high-rent development. But Barnes is raising important issues, and not just for his own district. City Council members should keep asking questions.

Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, its staff, or the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.