Transportation and equity: Approaching complicated questions as Charlotte grows

When it comes to transportation and transit in Charlotte, it seems like there are as many questions as there are answers these days. Add in equity and economic mobility, and the picture gets even more complex.

The UNC Charlotte Urban Institute’s second Schul conversation focused on these questions (the first explored gentrification and displacement). The panel discussion, moderated by Ely Portillo, our Director of Research Engagement, featured local and national experts, including Dr. Elizabeth Delmelle of the University of Pennsylvania, Meg Fancil of Sustain Charlotte, Maureen Gilewski of CharlotteEAST, and Jason Lawrence of CATS.

The panelists highlighted a variety of challenges:

-

What are the main goals of transportation policy?

-

What’s the right balance of transportation modes (roads versus buses versus rail)?

-

How do we pay for transportation infrastructure?

-

What system best meets the diverse needs of the full population, including around accessibility?

-

Who are the expected users of public transportation?

-

How should we think about the effects of transportation infrastructure on community demographics?

-

What is the best way to craft a cross-jurisdictional transportation policy that serves the entire Charlotte region?

-

How can bikes and parks contribute to the region’s transportation needs?

-

What do current and coming technological innovations mean for transportation policy?

-

What do changing work-from-home practices mean for the design of transportation policy and infrastructure?

You’ll notice that I framed each of those challenges as questions. Unfortunately, when it comes to transportation in the Charlotte region, such challenging questions are much easier to come by than answers.

That’s because transportation policy is a “wicked problem,” denying obvious solutions to even smart, selfless, knowledgeable people working hard and in good faith to benefit the community as a whole.

Policy problems can be wicked for two big reasons. First, some topics are inherently complicated, with so many moving parts that it’s hard to tease out the causal relationships between various factors. In other words, the “what is?” question is hard to answer, and so we wouldn’t know what to do even if we all wanted the same result.

Second, some issues present political challenges as different entities debate as to how to make the inevitable tradeoffs between values implicated in the policy choice. That is, the “what should be?” question is hard to resolve because different individuals and groups have competing interests and preferences.

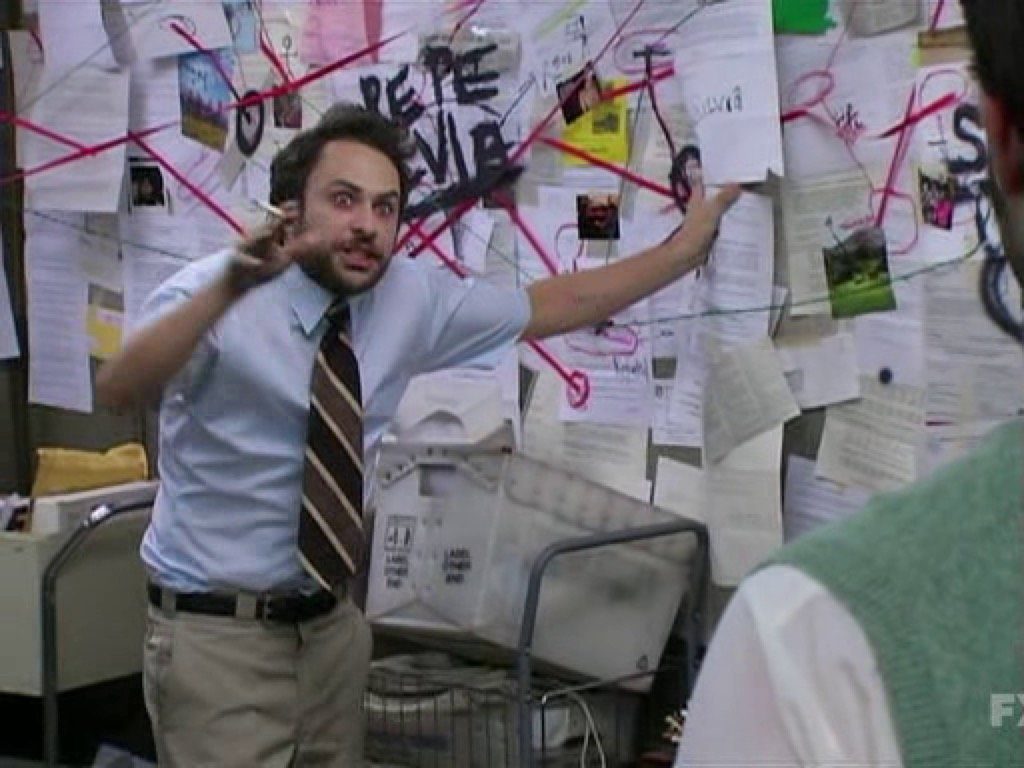

Transportation policy, unfortunately, presents both types of difficulties. Data aren’t readily available for everything we’d like to measure. Trying to diagram the relationships between important variables results in crazed maps with causal arrows pointing in every direction (see picture). And transportation planning inherently involves making predictions, which is always an exercise fraught with uncertainty and imperfection. The phenomenon of transportation is thus impossible for anyone to perfectly understand.

And the politics of transportation are no easier to figure out. The only thing we know for sure about transportation in the Charlotte region is that it will change. A failure to invest in transportation planning or infrastructure will mean people will experience significant changes in commuting times and congestion levels. And the construction of transportation projects comes with major costs–costs that won’t be borne equally by everyone. Those living in closer proximity to the investments will suffer more of the disruption while the infrastructure is being built. These groups will thus engage in political struggles to optimize their relative balance between costs and benefits–and no two people will make the same calculus.

The wickedness of the problem of transportation policy means the Charlotte region faces the threats of “paralysis by analysis” and “the perfect being the enemy of the good.” Inaction will not preserve the status quo–it is also a policy choice that will produce an alternative outcome. That default result could just happen to be the best possible outcome, but that’s unlikely. No plan will be perfect, and no plan’s process will be perfect. But any of a number of plausible plans offering paths forward would likely produce a better transportation system than no plan at all.

The Charlotte region has already been asking the right questions about transportation policy. No process or glossy policy document will be able to offer answers that satisfy every constituent. Rather than trying to design a perfect grand regional plan that will never be implemented because of all the veto players, policymakers should move quickly to craft coherent, feasible, smaller-scale policies that they expect to improve the status quo and can enact quickly (and abandon quickly, if they prove to be failures).

The Connect Beyond plan offers just such a thoughtful and flexible policy framework. Could every one of our panelists find something to criticize about it? Absolutely. It’s imperfect–just like every policy document ever, just like each of us. But it’s done. Adopting it would allow us to finally get past the “talking and planning” stage and to the “implementing” stage.

The goal shouldn’t be to get transportation policy exactly right. That’s impossible. The goal should be to get it less wrong.

The Institute will continue to convene conversations around this important, challenging policy issue. On November 17, 2022, the Institute will hold its annual Schul Forum at the University’s Dubois Center in downtown Charlotte. Registration details can be found here. The Schul Forum will feature a keynote address by Dr. Karen Chapple, an international expert in planning, transportation, and neighborhood change, along with a local panel to explore the topic as it relates to the Charlotte region. We hope you will join us.