What feeds the pollinators feeds us

A concrete walkway bisects my small front yard. I grow herbs and vegetables on one side and an assortment of native grasses and perennials on the other. In my mind, they’ve always been two distinct entities. One side feeds us, and the other feeds wildlife. I’ve recently had to reconsider that rigid dichotomy. The line between the two is more porous than the hardscape might suggest.

When the skies finally cleared after all those days of heavy rain in late August, I headed out to my vegetable garden to stake the pepper-laden poblanos that had toppled during the storms. A motion in my peripheral vision stopped me in my tracks. The nearby patch of garlic chives was buzzing with activity. There were literally hundreds of gnat-sized bees zipping around the clusters of white, star-shaped flowers.

I pulled out my phone and waited for one to land. It’s difficult to get detailed photos of an insect that small, but I managed to capture a few images and uploaded them to iNaturalist. As I suspected, they appeared to be some sort of sweat bee. I’ll probably never know the exact species, but I’m still hoping John Ascher, an entomologist at the American Museum of Natural History who sometimes confirms or corrects my observations, might be able to identify these tiny creatures that are apparently thriving in my urban garden.

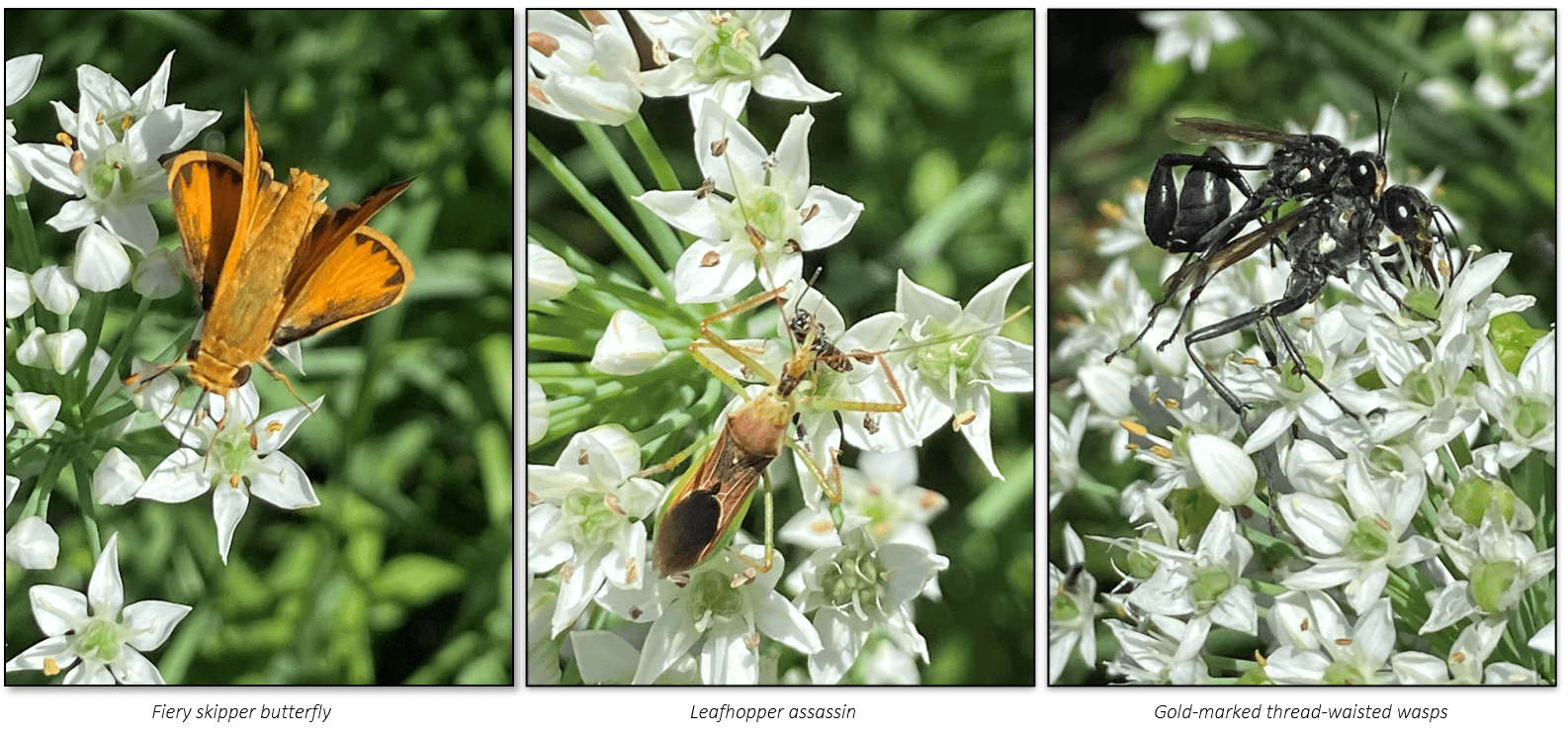

In addition to the sweat bees, there were other insects frantically going about their business on the garlic chives. Thus far, I’ve identified upwards of 30 different species – bees, wasps, butterflies, moths, bugs, beetles, grasshoppers, hornets and flies. The sweat bees and honeybees can generally be found throughout the day, but other species seem to come in shifts. One evening, I went out to gather some mint for dinner. I expected the garlic chives to be quiet after sunset, but I found a half-dozen small, rusty-colored moths flitting around.

All this insect activity on this exotic herb has blurred the lines between the plants I tend for human consumption and those I tend primarily for pollinators and other wildlife. The garlic chives seemed to be excelling at both.

Photos by Ruth Ann Grissom

Concern about pollinator decline is often focused on honeybees, especially in relation to food production, but this assumption is now being called into question. Elizabeth Hilborn, a veterinary scientist who specializes in treating honeybees, explored this topic in a recent issue of Modern Farmer (Are We Backing the Wrong Bee? – Modern Farmer). She notes that native bees can be more effective at pollinating some of our vegetables. Blueberries and squash, for example, have such a close association with their native pollinators, the bees are actually named for them.

Debbie Roos, a Cooperative Extension agent in Chatham County, created the Pollinator Paradise Gardens at Chatham Mills in Pittsboro (About the Chatham Mills “Pollinator Paradise” Demonstration Garden | NC State Extension (ncsu.edu)). While approximately 85% of the species she uses are native to North Carolina, she also includes several exotic herbs. She chooses the ones that excel in providing floral resources for nectar and pollen, but she also includes parsley and dill, which act as host plants for the black swallowtail butterfly. This role isn’t typical of exotic plants, and I’m certain there wouldn’t be such a diversity of insects on my garlic chives if I didn’t also have so many native plants growing nearby.

Bees and other pollinators use my lavender, rosemary, mint, oregano and sage, but I’ve never seen those plants create the frenzy I’ve witnessed on the garlic chives. Is their pollen or nectar really that intoxicating? Is it simply a timing issue? Maybe the days of heavy rain had suppressed their flowering and they all burst forth at once. Or maybe their bloom happened to coincide with a period when many insect species are on the landscape and are feeling the urgency of summer’s waning days. I formulated this theory after observing a pair of gold-marked thread-waisted wasps copulating while the female was foraging. An insect’s life is typically short, so I guess it isn’t surprising they sometimes multi-task.

The humble garlic chives have reminded me that what feeds pollinators also feeds us, either directly or indirectly. The late entomologist E. O. Wilson called insects “the little things that run the world.” He noted that insects can survive without us, but we can’t survive without them. If all the insects suddenly disappeared, he said, we would quickly starve to death. Thanks to all the insects attracted to my garlic chives, I now see my entire front yard as a single, unified garden.