When it comes to transit, everyone wants ‘regionalism.’ But no one’s quite sure how to get there.

There’s consensus in the new crop of local transportation plans: Whether we’re talking about trains, buses or roads, we’ll have to cross county borders and state lines to fund and operate an effective transit system.

But in the traditionally siloed Charlotte region, how do we actually create some kind of regional entity — and who will get to control the purse strings and make decisions?

Though the broad outline — regionalism is good, our current fragmented systems are, well, not great — clearly has some support among policymakers, it’s when you get into specifics that things get a lot murkier. And advocates concede it will take years, or decades, to agree to and build something like a regional authority.

In the meantime, how bad will congestion have to get before the barriers to regionalism break down?

“It’s crucial,” said Steve Yaffe, a Fort Mill-based transit consultant who previously worked in the Washington, D.C. area. “And the motivation, as usual, has to be pain.”

Three major, locally led transportation plans have been developed recently: Charlotte Moves, Connect Beyond and Beyond 77. All three concluded that we need some kind of regional funding and governance.

Connect Beyond, led by the Charlotte Area Transit System and the Centralina Regional Council, calls for studying “regional partnership structures” and figuring out how to seek money as a region. Charlotte Moves calls for funding from Union and Gaston counties to build the Silver Line light rail.

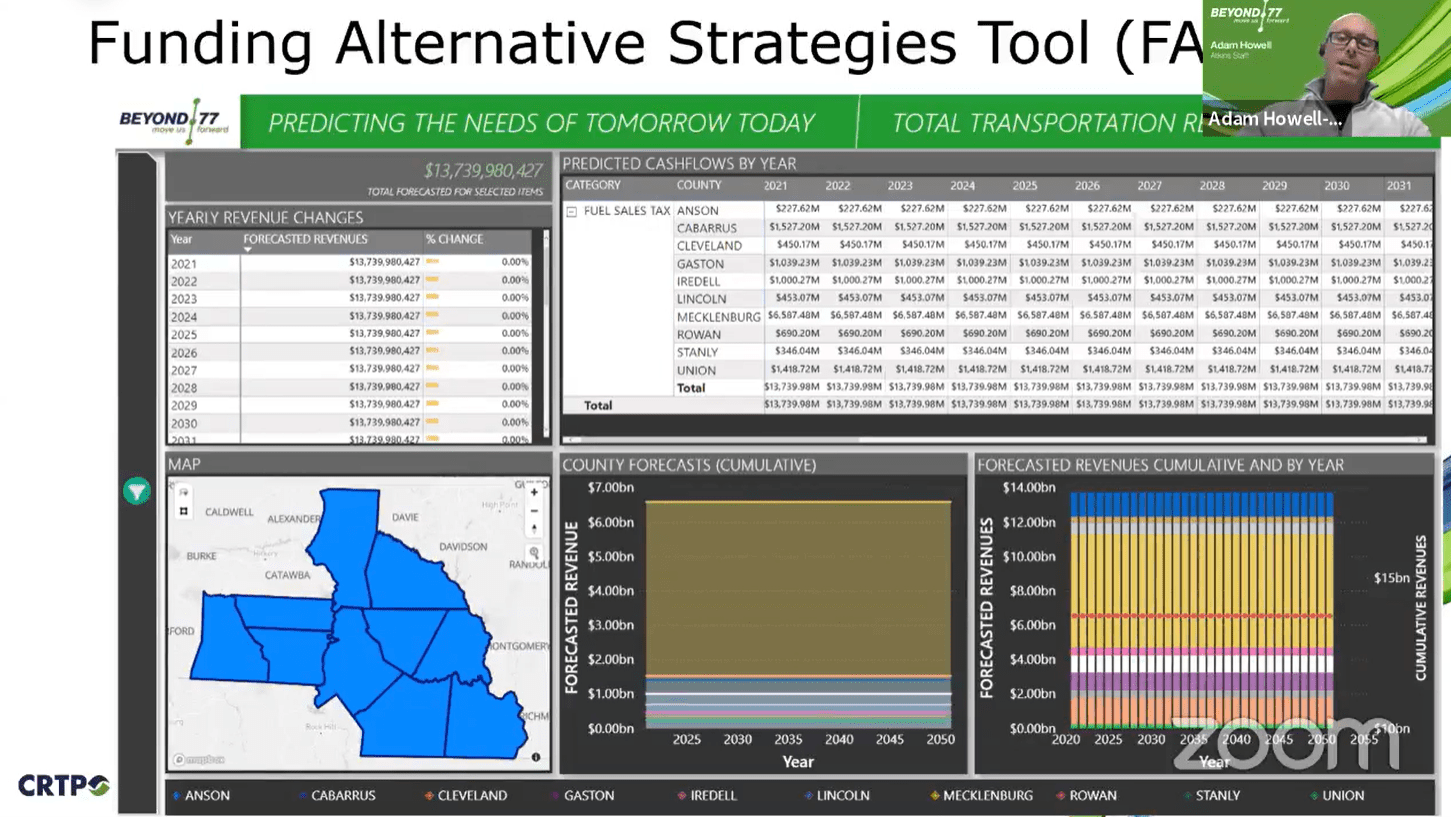

And Beyond 77, a planning initiative meant to improve the traffic-choked interstate, bluntly lays out acting “as a region rather than separate counties, municipalities, and MPOs (metropolitan planning organizations)” when it comes to funding and governance as a prerequisite for getting anything done. Beyond 77 also proposes some of the most aggressive regional funding ideas, including a regional sales tax, mileage-based usage fees, vehicle registration fees and a regional property tax.

[Transit Time: A Plan B for Charlotte’s transit expansion?]

But adopting even the most modest of those proposals would take a huge amount of work and a concerted push in the state legislature.

“It’s not going to be easy,” said Geraldine Gardner, head of the Centralina Regional Council. “It’s going to take a lot of intentional activity. We need to crawl, to walk, to run.”

Gardner said a full-fledged authority, with independent taxation powers and its own revenue streams, might not even be right for the region. It’s too early to say.

“That may not be what we need,” she said. A working group will be studying the possibilities, under Centralina’s direction, in the next phase of the Connect Beyond plan.

The big hurdle will be moving from planning and studying to actually doing something. The regional transportation planning discussion is a perennial subject in Charlotte. Ron Tober, the Godfather of Charlotte transit planning and former CATS chief executive, recalled city officials telling him when he was hired that we would need a true regional transit authority in “about 10 years.” Tober started working at CATS in 2000.

I myself tagged along on an intercity visit for city leaders to Denver in 2016. The main focus? Building and paying for a regional transit system. Six years later, activists are wondering where the action is.

“How is that going to go from talk to action?” said Shannon Binns, executive director of Sustain Charlotte. “We would really like to see a regional authority of some sort…You’ve just got so many actors, but no one’s really in charge.”

Alphabet soup planning

The Charlotte region’s transportation planning has historically been fragmented. The CATS chief executive reports to Charlotte’s city manager, while the Metropolitan Transit Commission serves as CATS’ long-term policy and funding board. The MTC includes regional members, but only in non-voting, ex officio capacity, meaning Mecklenburg leaders make the decisions.

Meanwhile, the rest of the region’s planning apparatus reads like bad attempts at a Wordle puzzle.

There’s CRTPO (the Charlotte Regional Transportation Planning Organization), GCLMPO (the Gaston-Cleveland-Lincoln Metropolitan Planning Organization), RFATS (the Rock Hill-Fort Mill Area Transportation Study) and CRMPO (the Cabarrus-Rowan Metropolitan Planning Organization). That’s in addition to the half-dozen smaller, independently operated regional transit systems offering scheduled bus service. Then of course there’s the North Carolina and South Carolina transportation departments, and the federal agencies that provide critical funding for large infrastructure projects.

Got that?

A screenshot of a virtual meeting of the CRTPO.

Nationally, Charlotte is a bit of an outlier. Of the top 20 U.S. cities, about half have regional transit systems that extend beyond one county, such as Denver’s eight-county transit system or the joint Metro arrangement between Maryland, Virginia and Washington, D.C.

Even that’s a bit misleading, because a significant share of the large cities with a single-county transit system cover enormous counties spanning multiple municipalities. The Los Angeles transit system covers a county with roughly the population of North Carolina. Phoenix’s transit system includes much of Maricopa County, which has a greater land area than four states.

But look at transit systems for a little while, and you’ll soon see it’s a lot more complex than dividing them into “regional” or “not regional.” There’s enormous variation in how different regions approach funding and operational decisions.

- The Metro system in Washington, D.C., for example, lets the states and District governments allocate funding, which has led to shortfalls and maintenance backlogs.

- Around Phoenix, different municipalities own their own transit assets while the system as a whole features common branding and administration.

- In the Seattle region, a three-county transit system runs trains, ferries and some buses, while local municipalities operate their own systems as well — with full fare interoperability between all of them.

In North Carolina, there’s one example of a regional transit authority: GoTriangle, which runs regional buses in Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill. Authorized by the legislature at roughly the same time as CATS, GoTriangle is funded in part by a $5 regional vehicle registration fee.

“There’s no shortage of different models out there,” said Garnder. “It’s a question of what’s going to work now for our region in the future, what’s legally allowed, and what’s the political appetite.”

Ox-goring?

Whatever comes next for Charlotte will depend in large part on the region’s appetite to work together — and people’s willingness to cede some local control to a greater body. That’s a big potential obstacle in a region where, historically, each county and municipality has more or less gone it alone.

“The problem is, ultimately somebody’s ox is going to get gored in the regional game,” said Charlotte lawyer and Republican political strategist Larry Shaheen. “Charlotte’s never going to give up control to a regional board, and the other regional players won’t create a body unless they can say ‘Charlotte, you’re not in control.’ So nobody winds up doing anything.”

Despite the above comment, Shaheen’s not a total regional pessimist. He thinks it can happen — if the business community, state and local elected officials agree to back a comprehensive infrastructure effort that includes roads, not just mass transit, and local governments cede some control.

That’s similar to the model that the Richmond, Va., region adopted in 2020. A new, multicounty authority oversees revenue from a sales and gasoline tax to fund transportation projects of all kinds.

Gardner mentioned Richmond as an intriguing model. But in any case, Gardner said a major challenge now is keeping the regional transit and transportation discussion from being eclipsed by other issues. The discussion has been going on for years, after all.

“A lot of the stakeholders who are involved in this process have other responsibilities, other priorities,” she said. “How do you keep transit on the front burner for very busy county mangers, county commissioners, private sector leaders who still have their own struggles?”

Tober, the former CATS chief executive, said he’s confident that a regional authority will emerge one day. But he’s not ready to predict how, exactly where, or when.

“It will happen,” said Tober. “Maybe not in my lifetime.”

This story was originally published in Transit Time, a newsletter jointly produced by the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute, WFAE and The Charlotte Ledger.