Who are Charlotte-Mecklenburg immigrants?

On Feb. 27, the Charlotte Mayor’s Immigrant Integration Task Force met for the first time. Around the same time, Charlotte Chamber President Bob Morgan signed a letter by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Partnership for a New American Economy to House Speaker John Boehner, urging him to move immigration reform forward this year.

While the chances are slight for federal action to address current immigrant policy challenges, the question of how our local leaders respond to a growing stream of foreign-born Charlotteans has shifted dramatically. Taking the 2007 Mayor’s Immigration Study Commission Report as a starting point, the Mayor’s Task Force is charged to “… research and recommend policies that facilitate access to city services, … address gaps in civic engagement, … seek opportunities to better educate the Charlotte community on how embracing immigrant communities will help move the city forward.”

|

Learn More The Census data used in this post are available at the Mayor’s Immigrant Integration Task Force website. See a slide presentation, Immigrants in Charlotte: A Statistical and Spatial Overview.” |

But, one of the first challenges for the task force members is to develop a clear understanding of who Charlotte’s immigrants are. The popular impression is that our city’s immigrants are overwhelmingly from Latin America and largely working in the blue-collar service jobs. Moreover, critics of immigration tend to portray these newcomers as undocumented and reliant on public services and assistance.

The reality is far more complex. Charlotte is a globalizing city; as such, it attracts new residents, both domestic and international, from across the socioeconomic spectrum. So, yes, the person taking your order at the neighborhood fast-food restaurant may have a foreign accent, and the crew moving materials around a Westinghouse Boulevard warehouse may be listening to Afro-pop on the radio. But, the cardiologist at Carolinas HealthCare System treating your spouse and the center city banker selling capital market products to customers around the world are also increasingly likely to be immigrants.

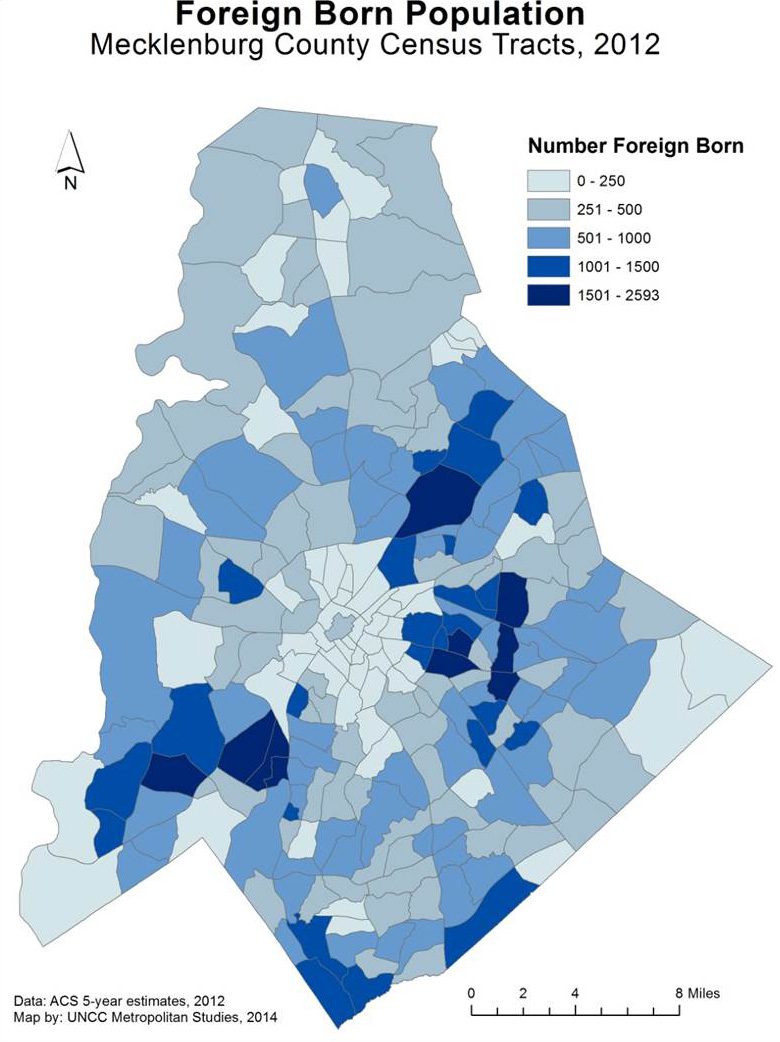

Using the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent American Community Survey, we can develop an overview of foreign-born Charlotteans. A conservative estimate is that they are close to 130,000 of your neighbors, making up around 14 percent of Mecklenburg County’s total population. A majority (50.7 percent) of these immigrants arrived in the United States before 2000. Yet, like domestic immigrants, the stream of new arrivals to Charlotte-Mecklenburg did not slow during the Great Recession. Charlotte may have faced deep economic doldrums, but nearly 6 percent of the immigrants have arrived post-2010, a testament to the city’s continuing attraction as a place in which to secure work and build quality of life. (See the distribution of foreign born population within Mecklenburg County in the map below.)

The region of birth for immigrants to Charlotte-Mecklenburg is varied. A slight majority (51.5 percent) were born in Latin America. But more than 27 percent were born in Asia, including large proportions coming from India and China. Europeans make up a sizeable 10.9 percent, followed by Africans, 8.4 percent. For geography nerds, the Census Bureau boundaries split the closely watched Middle East region between North Africa, assigned by Census geographers to Africa, and the historical Middle East, apportioned to Asia.

The data do not bear out the popular image of immigrants as poor and confined to low-wage jobs. The median household income for immigrants is $54,419, or 96 percent of what the median native-born Charlotte family earns. Six percent earn more than $200,000, with another 18 percent making more than $100,000. Many are poor; almost 12 percent make less than $15,000, and the next 10 percent make less than $25,000. What about the types of jobs immigrants are filling? More than one-quarter (26.9 percent) work in the management, business, science or arts occupations, generally what are called professional fields. Fewer are employed in natural resource, construction, and maintenance occupations, 19.67 percent. These are generally categorized as blue-collar jobs.

While these data test our perceived notions, a closer analysis reveals divergent differences between Charlotte-Mecklenburg immigrant streams. Not unexpectedly, if one takes into account educational background, language skills and citizenship status, there are powerful effects in immigrant quality of life and receptivity. Through this lens, Charlotte’s immigrants from Europe occupy the top rankings, followed, in order, by Asian, African and Latin American-born immigrants. If we cross-reference these groups against native-born Charlotteans, the European and Asian newcomers are comparatively better off than natives on several educational and economic measures, while Africans and Latin Americans score below the U.S.-born group.

Taking into account the myriad factors affecting immigrant integration, the facts on the ground are that Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s immigrant community is far from monolithic.

What this means is that we need to be strategic if we are going to become a “welcoming city.” A “one-size” policy or plan that targets immigrants born in one region is not the way to go. The good news is that through efforts like the Mayor’s Immigrant Integration Task Force, many of the city’s leading agencies and institutions are working together to move Charlotte and Mecklenburg County forward to reach its full potential as a leading 21st century global community.