Who you befriend affects your economic mobility

When it comes to economic mobility – low-income children’s ability to rise from poverty – we’ve known for a while that where you live influences your chances of success. Now, a new study suggests it’s not just where you live, but who you know that can tip the odds.

A vast new project looking at the connections between tens of millions of young adults provides the clearest picture yet of how social capital and connections across different socioeconomic levels can increase economic mobility. The data, based on more than 70 million Facebook profiles, covers 82% of people aged 25-44 in the U.S. – or more than 21 billion “friendships.”

“Many have argued that the strength of an individual’s social network and community — their social capital – may have an important effect on outcomes ranging from health to education to earnings,” explained study author Raj Chetty. “But measuring social capital has proven to be difficult, with most work to date having to rely on small surveys or indirect proxies, limiting our understanding of what social capital really is and why it matters.”

Using this enormous dataset, Opportunity Insights (the same research group led by Raj Chetty that named the Charlotte region 50th out of 50 for economic mobility in the U.S.) computed how likely low-income people were to be friends with high-income people. Their analysis goes down to the zip code, high school and college level.

[Explore the interactive Social Capital Atlas]

The results are available in an interactive “Social Capital Atlas” that allows users to see those connections mapped out. A quick perusal of the Charlotte region immediately shows some interesting contrasts:

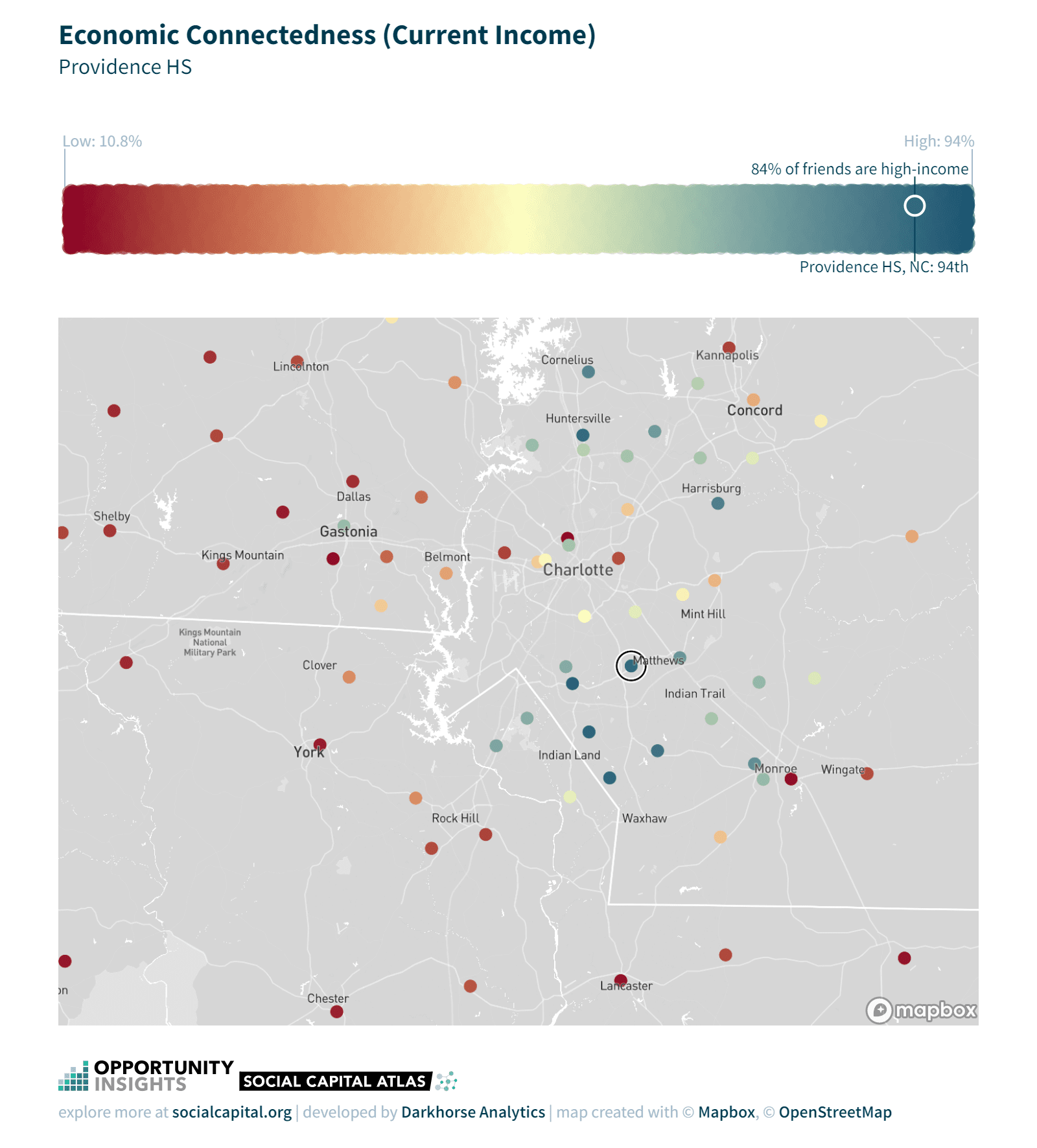

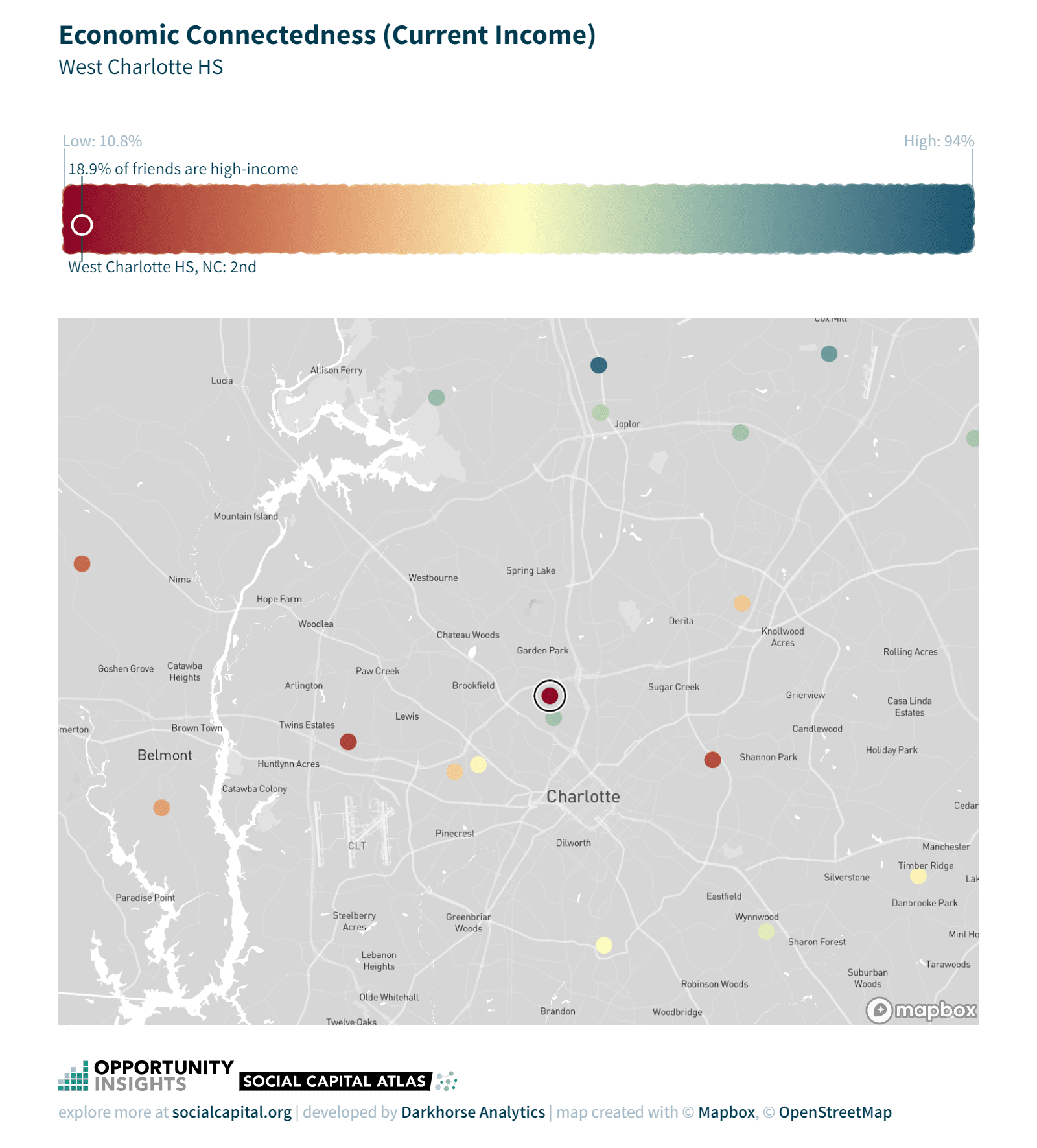

- There’s a big difference between how likely low-income individuals are to be friends with high-income individuals based on where they went to high school. At Providence High School and Hough High School, 84% and 75.6% of low-income individuals’ friends are high-earners. Compare that to 18.9% at West Charlotte High School. Providence and Hough are both relatively high-income schools located in largely White communities, while West Charlotte is lower-income and located in a largely Black neighborhood.

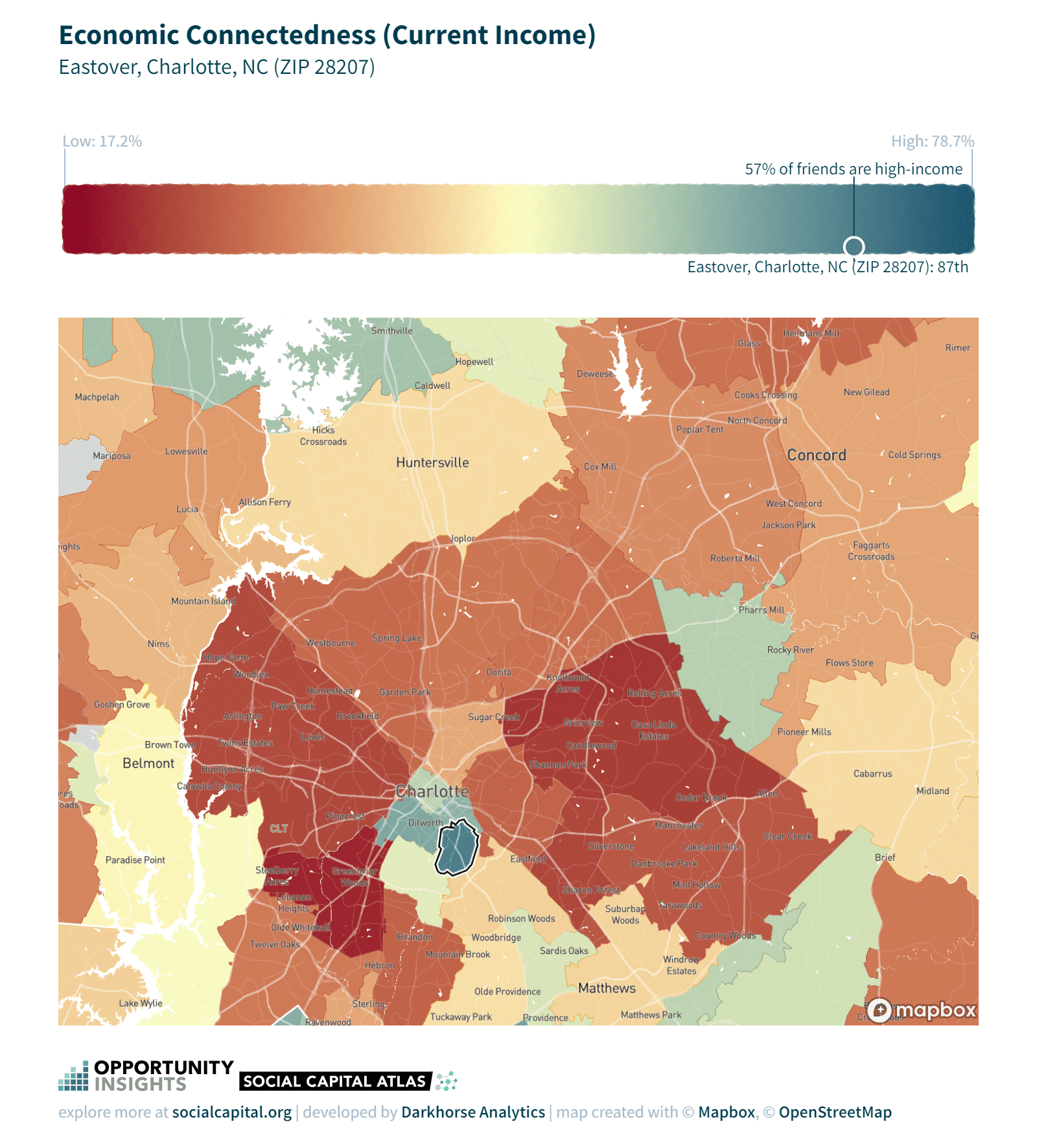

- There are also big differences in ZIP codes. In 28203 (the area encompassing Eastover and Myers Park), 57% of low-income individuals’ friends are high-income. It’s 52.5% in 28277, covering Ballantyne and south Mecklenburg. But in 28217, covering much of west Charlotte, it’s only 27.3%.

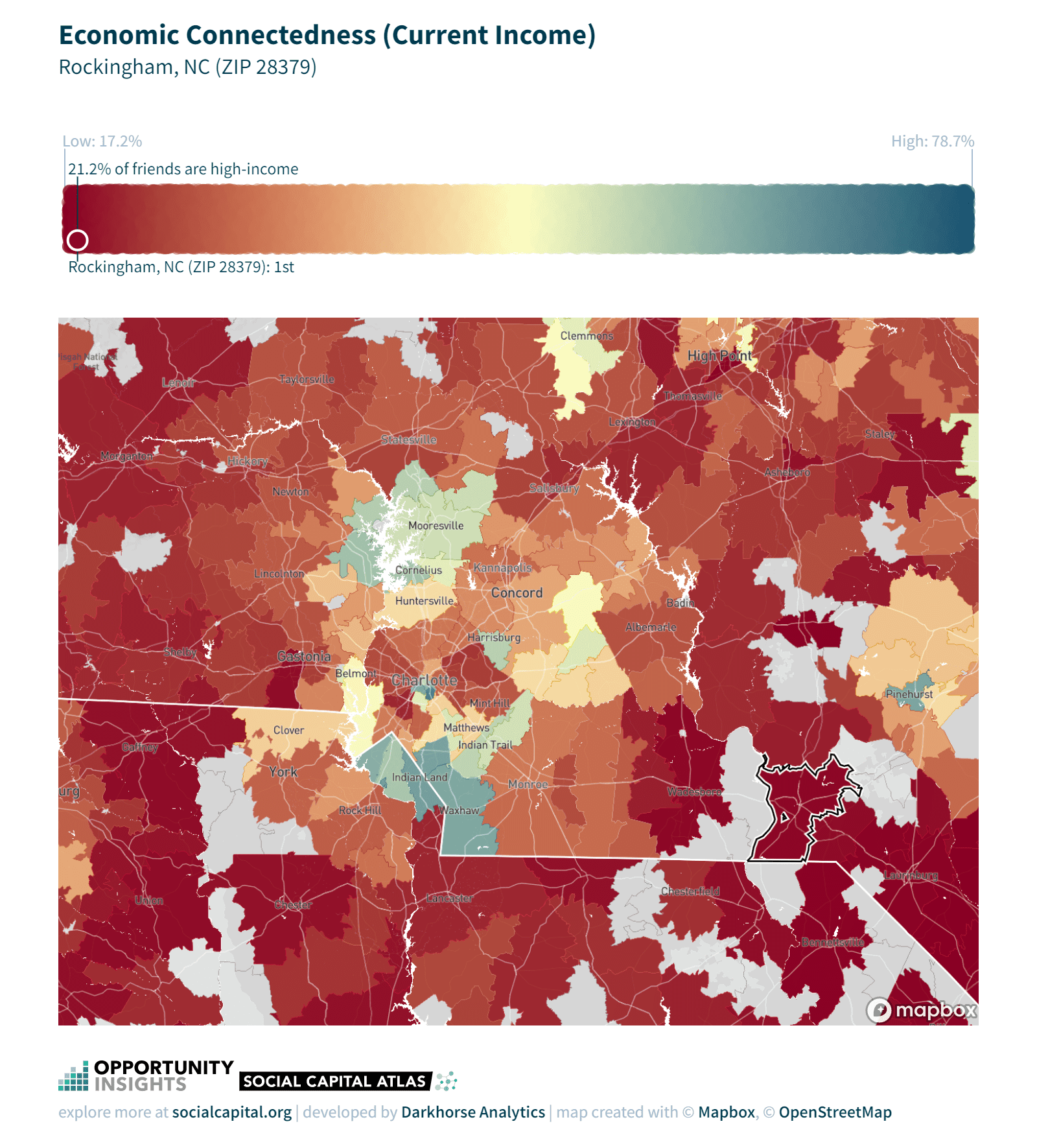

- Beyond Mecklenburg, regional disparities are pronounced as well. For example: While 51.9% of low-income individuals’ friends are high earners in Waxhaw, only 21.2% are in Rockingham.

This de facto segregation by class of who we know is the strongest predictor of economic mobility, the researchers found. And “economic connectedness,” or forming friendships across this divide, appears to be the most powerful way to help children from low-income families climb the economic ladder.

“Growing up in a community connected across class lines improves kids’ outcomes and gives them a better shot at rising out of poverty,” said Chetty, a Harvard University economist and Opportunity Insight’s director, told the New York Times.

Then researchers attributed half of the disconnectedness across class lines they observed to lack of exposure (low- and high-income children going to different schools, for example), and half to friending bias (low-income and high-income children at the same schools forming friendships with people similar to them).

That suggests that, in addition to measures that reduce the segregation of schools and neighborhoods (such as bussing or allowing more density in established single-family neighborhoods), we should also look to promote friendships across class lines once people are in the same location.

“In some communities, it may be more fruitful to focus on increasing integration to increase cross-class interaction; in others, it may be more effective to focus on reducing friending bias,” the researchers wrote. “More broadly, beyond direct efforts to increase cross-class interaction, our analysis suggests that providing relevant bridging social capital may make other programs that seek to increase economic mobility more effective as well. For example, recent programs that have had large impacts in helping families move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods or obtain higher-paying jobs provide bridging social capital and outperform traditional programs that focus solely on economic resources or skills.”

You can find a detailed explanation of the study’s methodology, including how they created their dataset, anonymized data and estimated income levels, as part of the full paper published in Nature.