Will companies pay millions for naming rights by Charlotte’s bus station?

Would you spend $750,000 to put your name on Charlotte’s new uptown bus station?

A consultant told a City Council committee this week that he expects a company would buy the naming rights to the new facility, scheduled to open by the end of the decade.

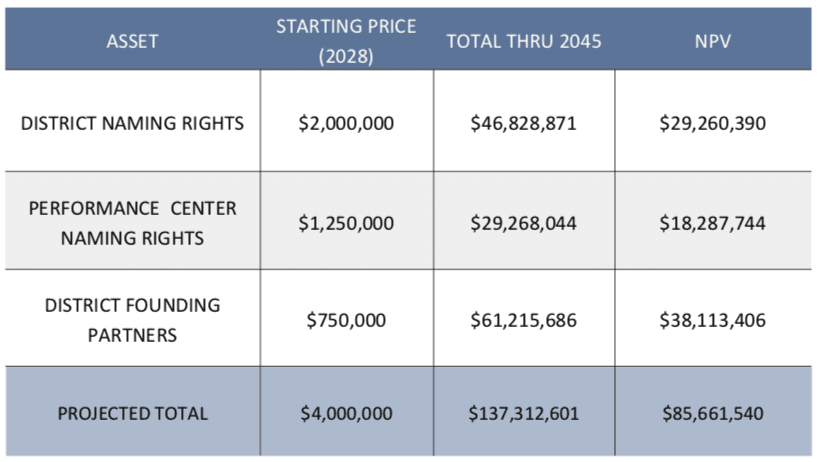

Sean Moran with the Innovative Partnership Group said the city could make a cumulative $137 million by 2045 through selling off naming rights to the bus station and other assets in its planned “festival district” on Brevard Street.

“These are realistic targets,” Moran told City Council members at a committee meeting Monday.

Is that realistic? And would any businesses pay that kind of money?

First, let’s start with the background.

The city plans to tear down the main bus station on Trade Street across from the Spectrum Center.

The Charlotte Area Transit System will rebuild the station underground, clearing the way for a new mixed-use tower on the site, with offices, hotels, stores and apartments or condos. The tower might include a new practice facility for the Charlotte Hornets.

With the buses (and bus passengers) mostly hidden, the city says the area near the arena can become a “festival district,” where people hang out before and after events at the Spectrum Center. It’s an underdeveloped slice of uptown, dotted with surface parking lots and the former Epicentre entertainment complex.

The envisioned “festival district” would be along Brevard Street, between the Spectrum Center and the Charlotte Convention Center. (From City of Charlotte presentation)

The envisioned “festival district” would be along Brevard Street, between the Spectrum Center and the Charlotte Convention Center. (From City of Charlotte presentation)

Moran said the city could sell the naming rights to the entire area – a first for Charlotte. As an example, he pointed to names like “The Bank of America District” or “The District Presented by Bank of America.”

He also said the city could sell naming rights to the NBA practice facility, as well as naming rights to smaller parts of the district, like the Rail Trail, a possible food hall, and, yes, the transit center itself.

The city’s consultant envisions naming rights for the “festival district” to start at $2 million a year, rights for the Hornets’ training facility to start at $1.25 million a year and signing up five “founding partners” at an average of $750,000 each per year. The deals could bring in $137 million by 2045, he estimated.

He projected $4 million in revenue in the first year, with escalating prices annually to keep up with inflation. That would amount to nearly $140 million by 2045.

Let’s start with the main bus station.

Would someone want to sponsor the transit center?

Before the pandemic, some transit agencies did sell naming rights to train stations and even train lines. In San Diego, for instance, the transit agency sold the naming rights to a rail line to a casino. The “Sycuan Green Line” name is expected to generate $25.5 million for the agency over 30 years.

The American Public Transit Association said it’s aware of only two naming rights around buses. One is in Cleveland, where a hospital system bought the naming rights to a bus rapid-transit line. The other is in San Francisco, where Salesforce’s name is on a bus transit center that will eventually have rail.

It’s possible that some transit agencies have had more success selling naming rights to train stations because rail users have higher incomes than bus passengers. In Charlotte, 47% of bus riders are very low-income, making less than $25,000 a year, so there may not be an incentive for a company to spend on naming rights.

Another hurdle to selling naming rights in Charlotte may be crime.

City economic development director Tracy Dodson has said the existing transit center is a “public safety problem.” A 2019 story in the Charlotte Observer about the failing Epicentre noted that “across the street, the Charlotte Transportation Center reported 22 crimes involving a gun. Only the airport had more – and most of them were nonviolent weapons law violations.” More recently, a person was shot there and taken to the hospital in November 2022 following an argument, police said at the time.

The city has said the new underground design will be more secure and safe by allowing only ticketed passengers to enter.

That’s a key point if the city wants to have any chance of selling naming rights to the bus station.

And it’s a key point for the surrounding “festival district” to succeed.

Hornets practice facility naming rights

There is a good track record for selling these rights. In fact, the team’s current practice facility is sponsored by Novant Health (the arena is sponsored by Spectrum).

Moran said most NBA teams have sponsorship deals with healthcare providers already for their practice facilities. Selling the naming rights for a new facility should be relatively easy.

Naming the entire district

This is the biggest piece of the pie. Moran said this could generate $2 million in the first year, with that fee increasing over time.

As an example, he cited the Nashville Yards development, which has three primary sponsors, including Pinnacle Financial Partners.

But Nashville Yards is a massive new development, with 3 million new square feet of office; 1,000 new hotel rooms; 2,000 apartments; and a 4,500-seat theater.

The main difference between Nashville Yards and Charlotte’s planned Brevard festival district is size.

Nashville’s development is 18 acres. The new Charlotte tower (the only announced project for the “festival district”) sits on a little more than 3 acres. (You could count the Spectrum Center as part of Charlotte’s festival district, even though it already has a corporate name and is nearly 20 years old.)

Throwing shade at the NASCAR Hall of Fame

Fifteen years ago, city leaders were touting the NASCAR Hall of Fame as a catalyst like the proposed festival district.

Those plans fizzled.

Attendance at the city-owned museum never met projections. Today, the hall’s main plaza is almost always empty, except for a few people walking into the Buffalo Wild Wings.

But as council members discussed the new festival district, they memory-holed the NASCAR Hall of Fame, which cost nearly $200 million. Most of that was public funds.

The city’s consultant – Moran – cast the Hall as a tacky intrusion on his vision for Charlotte’s festival district. “How do you generate and maximize revenue but in an authentic way?” Moran said. “I think we want to avoid a NASCAR Hall of Fame feel where you are seeing a lot of brands slapped around or a lot of LED signage.”

Under Moran’s proposal, the city would sell naming rights for:

- The overall festival district

- The Hornets facility

- The transit center

- The rail trail

- A food hall

- The festival street

Mentioning NASCAR Hall of Fame reminds us of…

This is not the first time the city of Charlotte has pushed for an entertainment/festival area.

In 2008, Epicentre opened, just two blocks from the site of the proposed “festival district.” Epicentre was a mostly privately led project, though it did receive some public money for infrastructure.

The restaurant/bar cluster peaked in 2012 during the Democratic National Convention and then began a slow death spiral. Today, it’s mostly vacant. Last year, it was renamed “Queen City Quarter,” and its owner is planning repairs and renovations to try to lure new tenants.

Before the Epicentre, there was a true city-led festival concept: CityFair. It opened in 1988 at 6th and College streets as a collection of shops and restaurants. It was demolished a decade later. At the time, the city called it a “festival marketplace.”

A generation later, the city has done a bit of rebranding for today’s proposed project, landing on “festival district.”

Presented by … someone.

Steve Harrison is a reporter with WFAE, Charlotte’s NPR news source. Reach him at sharrison@wfae.com. This story was originally published as part of the Transit Time newsletter, jointly produced by WFAE and the Charlotte Ledger.

Steve Harrison, WFAE