Will we ever learn from disasters?

The March 11 earthquake and subsequent tsunami that devastated the northeast coastal area of Japan has highlighted the extreme vulnerability of man-made infrastructure to natural hazards. Despite tremendous advances in engineering and construction, disasters of this magnitude lead us to question whether or not we should build infrastructure robust enough to withstand such a devastating disaster.

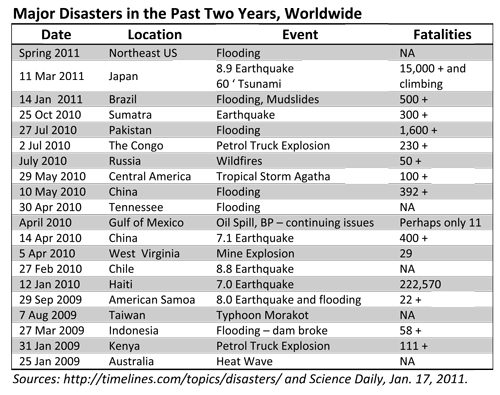

Over the past two years, some 20 major events have resulted in thousands of fatalities and billions of dollars in damages. The cost to replace or restore “critical infrastructure” damaged in such disasters places tremendous financial strain on people and institutions for years after the disaster. Note that in Haiti, there were over 222,000 fatalities! More than a year has passed and hundreds of thousands of victims of that earthquake are still in refugee camps. The listing of disasters in the table below is of course not complete because data are not universally available. Further, we have not listed dozens of major technological or human-induced events that have occurred over the past two years.

This essay focuses on certain aspects of major, high impact, low probability disasters. In one way of looking at such events, the general public views all disasters as low probability, primarily because the general public seldom thinks that any type of traumatic event like those listed in the table will ever affect them personally. In other words, they are not aware that, in the words of political scientist Scott Sagan, “things that have never happened before happen all the time.”1

We often hear professionals directly involved in emergency management state that “all disasters are local.” This means that local emergency response agencies, law enforcement, NGOs, etc. are usually there first with their “boots on the ground.” This relates to the fact that in the aftermath of a disaster, local people are usually in a position to ascertain the specific impacts and problems, and subsequent needs of the local citizenry, more clearly than anyone located in their state capital or even further away in a federal government location. In spite of this reality, there is still the need for local officials to consider working with their regional, state, federal and NGO partners in planning and preparing for a disaster ahead of time; in other words, forging, adopting and regularly updating a local Pre-disaster Mitigation (PDM) Plan.

The challenge to the global community for 2011, as the disaster in Japan brings these issues to the forefront, is to try once again to take a global approach to understanding better the consequences of not being truly prepared for high impact, low probability disasters. The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake, the fifth largest since 1900, the subsequent dozens of aftershocks, the devastating tsunami, and the very real potential for a major contaminant release serve as a stark warning that not planning for the worst can have national, if not global consequences. What is needed is a series of “layers” of PDM planning that takes advantage of the perspectives of professionals in a range of specialties, from those with high-level organizational and leadership skills to those first responders who arrive first at the scene.

The challenge to the global community for 2011, as the disaster in Japan brings these issues to the forefront, is to try once again to take a global approach to understanding better the consequences of not being truly prepared for high impact, low probability disasters. The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake, the fifth largest since 1900, the subsequent dozens of aftershocks, the devastating tsunami, and the very real potential for a major contaminant release serve as a stark warning that not planning for the worst can have national, if not global consequences. What is needed is a series of “layers” of PDM planning that takes advantage of the perspectives of professionals in a range of specialties, from those with high-level organizational and leadership skills to those first responders who arrive first at the scene.

What can we learn from previous disasters? Can we actually learn and apply those lessons and not simply document what happened? The need is for an international, coordinated, collaborative, and comprehensive system to address the processes that create possible turning points in disaster risk reduction. Unfortunately, three problem areas continually seem to interfere with our efforts to make much progress in planning ahead:

1) The complexity of modern, particularly urban life, which often places a greater priority on issues related to the economy, the maintenance and upgrading of our transportation, communication, and utilities systems, and our social networks. In other words, we’re busy keeping up with our daily responsibilities.2

2) Apathy on the part of the general population (except when directly or indirectly affected by a major disaster, of course), also affects elected officials and the public agencies they oversee. This overall apathy results in a lack of interest in the issues, which in turn leads to underfunding for the type of research needed for better understanding of the problems, and little action aimed at correcting those problems.

3) Failure on the part of decision-makers in the public and private sectors involved in disaster management, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), to join forces to integrate knowledge from the fields of science, engineering, and public policy, and to produce effective, continuously maintained local pre-disaster mitigation plans.

We must overcome these barriers, and in doing so,we must involve both researchers and practitioners on a global scale to increase the level of interest and accomplishments in education and research. Documentation of the effects of a disaster evolves over time by tracing every step in the emergency management process, from the time a hazard’s possibility of happening is determined to be eminent, to the following sequence of responses:

1. A warning is issued (if possible) to the populace that lives or works in the path or area of the hazard;

2. Evacuations or “sheltering in place” are carried out with the help of emergency management agencies, if time permits;

3. Emergency response;

4. Search and rescue;

5. Disposition of fatalities;

6. Short-term recovery; and

7. Long-term financial and technical assistance.

It is the last two steps in this emergency management sequential process that stand to benefit most from the careful development and periodic review of a Pre-disaster Mitigation Plan. There is much less attention and fewer resources being addressed at pre-disaster planning, and this is a world-wide issue. Any Pre-disaster plan, when completed, should be integrated with other plans for adjoining areas, and (in the United States) be approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). In effect, the emergency management process should begin with an activity, and a mind-set, that pre-disaster planning is the first in sequence, and most important element, of all the steps.

One critical aspect of major events such as the drastic flooding that has occurred in many areas is the “cascading effect.” This is the primary reason that pre-disaster planning on a global scale is needed. Simply worded, major disasters are complicated, as the following excerpt from a post Hurricane Katrina analysis attests: “(W)hen Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans and the surrounding area in the fall of 2005, the cascade started with hurricane force winds and heavy rainfall; it then spread to overtopped and breached levees; flood waters up to 12 feet; lost electrical power and communication; random fires; random looting; HAZMAT spills in the flood waters; inaccessible transportation routes; untreated sewage in the floodwaters; undrinkable water; submerged petroleum tanks floating to the surface; wild animals, snakes, alligators throughout the area; trapped residents; no supplies or electricity or medical services in hospitals; closed hospitals; closed services; former residents not returning; severely diminished economy.”3 We are now witnessing this same cascading effect in Japan.

While North Carolina is not at risk for high magnitude seismic events like the Tohoku earthquake, our state is subject to other serious hazards such as ice storms, hurricanes, and tornados. Small tremors occur periodically, however. (In fact, a report was issued earlier this week by the U.S. Geological Survey measuring a magnitude 2.9 quake on March 21 along the North Carolina/South Carolina border between Wadesboro, NC and Chesterfield, SC.) Our state and local governments have for decades now been active in developing pre-disaster plans on a county-by-county basis. Recently, the 17-campus University of North Carolina System has initiated this process. The UNC System’s campuses are located in 14 counties from the east coast to the far western corner of the state. Over the past three years, these campuses have begun to collaborate on developing and maintaining their individual Pre-disaster Mitigation Planning (PDM) processes.

UNC Charlotte, through the Regional Center for Disaster Studies and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, plus Zapata, Incorporated, an international consulting firm based in Charlotte, have provided technical support to develop these campus plans. These PDM planning activities have been encouraged and supported by the UNC General Administration. Campuses in the western part of the state have completed their initial drafts; some of the eastern campus plans are still under development. In each case, surrounding local communities and counties serve as coordinating entities to the extent that university campuses are a part of the larger community. Goals and objectives of the campus mitigation plans have started to coordinate with appropriate local governments in the spirit of collaboration and mutuality, reducing vulnerability to natural hazards for our campuses and for their surrounding communities.

In order to inform and educate our university community and the greater Charlotte region on the issues of disasters as outlined in this essay, the UNC Charlotte Regional Center for Disaster Studies will co-sponsor a seminar on campus on Thursday, April 21, featuring Dr. Tom Birkland, William T. Kretzer Professor of Public Policy at the School of Public and International Affairs, North Carolina State University. Dr. Birkland has spent his entire professional career in studies of hazards and disasters.

Brian Zapata wrote this article while a graduate student working at the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute in 2011.

1 http://understandingkatrina.ssrc.org/Clarke

2 http://homelandsecuritynewswire.com/problems-major-disasters

3Hauser, E., Elmes, S., and Swartz, N., “Risk, Preparation, Evacuation and Rescue,” in Richardson, H., Gordon, P., and Moore, J., eds., Natural Disaster Analysis after Hurricane Katrina, Edward Elgar Publishing, Ltd., Cheltenham, UK., p. 114 (2008)

Brian Zapata