A year later, were tornado lessons learned?

It’s that time of year again – for changing skies and summer storms. A little more than a year ago, early on March 3, 2012, an unannounced tornado blew through parts of Harrisburg and eastern Mecklenburg County. The twister injured four people, destroyed six homes and left 41 others uninhabitable or with major damage – all in a nine-minute rampage. The full impact came to light as the sun rose: Nearly 200 homes had been affected.

Fifteen months later, have we rebuilt? And what lessons were learned? Emergency officials in Cabarrus and Mecklenburg counties said the two-county tornado highlighted a need for better communication between counties. Cabarrus has also worked to improve its ability to assess storm damage. Questions remain about whether Charlotte needs a better tornado warning system – and why the largest city in the Carolinas is so far from the National Weather Service forecast offices, which are in Raleigh, Columbia and Greer, S.C.

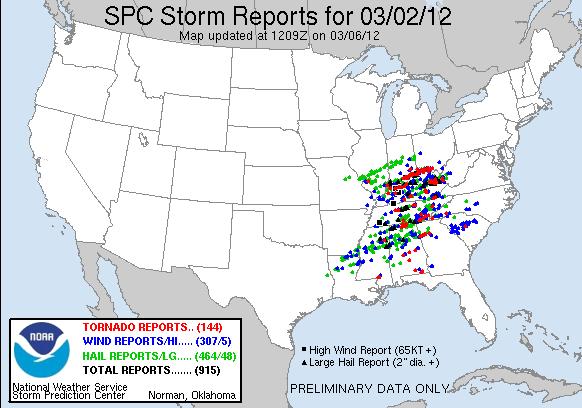

On March 2 and 3, 2012, a sig nificant outbreak of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes swept across the Tennessee and Ohio valleys and the western Appalachian Mountains. More than 100 tornadoes were reported, including several long-track killers across parts of Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky. More than 500 reports of wind damage and large hail were also received (see map at left). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calls the event reminiscent of, though smaller than, the “Super Outbreak” in April 1974.

nificant outbreak of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes swept across the Tennessee and Ohio valleys and the western Appalachian Mountains. More than 100 tornadoes were reported, including several long-track killers across parts of Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky. More than 500 reports of wind damage and large hail were also received (see map at left). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calls the event reminiscent of, though smaller than, the “Super Outbreak” in April 1974.

Part of last year’s outbreak was the Harrisburg tornado, which touched down around 2:30 a.m. near the intersection of Dulin Creek Boulevard and Little Whiteoak Road in eastern Mecklenburg’s Reedy Creek neighborhood (see photos below), just 4 miles southeast of the UNC Charlotte campus. It carved a 3.2-mile northeasterly path through two residential neighborhoods south of Plaza Road Extension, crossed Interstate 485 and continued through neighborhoods off Robinson Church Road in southwest Cabarrus County (see map below).

The tornado lifted around 2:39 a.m. northeast of Peach Orchard Road. Four people had been injured and almost 200 homes were damaged. In Mecklenburg County, 29 homes suffered major damage or were uninhabitable; another four were destroyed. A young boy was plucked from his home and recovered from the debris strewn in Interstate 485. In Cabarrus County, 12 homes sustained major damage and two were destroyed.

The EF-2 tornado, its winds hitting 135 miles an hour, left behind damage later estimated at $3 million, with many families unable to return to homes deemed uninhabitable. The storm’s toll was both physical and emotional.

Ray Carter lives in the Mecklenburg neighborhood of Brookstead, across the street from one of the homes destroyed. He is quoted in a May 2013 news report saying his son “sleeps with his sneakers on just in case it happens again, so it’s definitely an emotional rollercoaster.” While some residents have returned, Carter’s friends and their children have not. “We still stay in touch with them, but it changed our whole community,” he said (see photos below).

Ray Carter lives in the Mecklenburg neighborhood of Brookstead, across the street from one of the homes destroyed. He is quoted in a May 2013 news report saying his son “sleeps with his sneakers on just in case it happens again, so it’s definitely an emotional rollercoaster.” While some residents have returned, Carter’s friends and their children have not. “We still stay in touch with them, but it changed our whole community,” he said (see photos below).

Public reaction was quick following the tornado, and serious questions were raised. Why was no tornado warning issued? Why doesn’t Charlotte have a siren system to alert its citizens of an impending emergency?

Within days, WCNC-TV meteorologist Brad Panovich provided a detailed account of the tornado’s formation and path on his weather blog, and answers to some questions. He followed the storm the entire night, using social media and the station’s online feed after the regular broadcasts ended.

Panovich watched the storm build up and then suddenly appear as a tornado on the TV station’s Doppler radar. Immediately, Panovich began urging people in Cabarrus County to seek shelter, although it was too late for those in Mecklenburg. No warning had come from the National Weather Service.

In Panovich’s opinion, the tornado spun up so quickly there was no time to issue a warning in Mecklenburg County. “However,” he wrote, “there was no excuse why there shouldn’t have been a severe thunderstorm warning in place for Charlotte and Mecklenburg County … No one should have been unaware that severe weather was possible overnight.” Panovich saw the main reasons for the lack of warning as a combination of meteorological, human error, and political causes.

The way radar images are generated, Panovich explained, involves a 5- to 6-minute lag between scans, which means a fast-forming tornado might not show up on one scan, but then be apparent on the next. And at 2:30 in the morning, human spotters aren’t particularly useful either.

Contributing to the lack of warning, Charlotte is the largest U.S. city not sufficiently covered by Doppler radar.

Charlotte lies on the farthest borders of three different National Weather Service forecast offices. The Greer, S.C., office is 79 miles from uptown Charlotte. Raleigh’s is 130 miles away; Columbia’s is 84 miles away. This means the Doppler radars scanning for tornadoes across the Charlotte area are looking at the outer limits of their capabilities. One dedicated radar owned by the Federal Aviation Administration helps cover Charlotte’s airport, but it has limitations; it’s meant to detect wind shear at close ranges and has much lower power than the NWS Doppler radar. “The lack of a radar, and the area being split between offices, makes for a coordination nightmare,” said Panovich.

Politics may also have played a role in Charlotte’s precarious situation of lacking a local NWS office equipped with a Doppler radar. The weather service previously had an office in Charlotte that used an older type of radar. When Doppler technologies made them obsolete, offices were consolidated closer to large metropolitan areas to accommodate the expanded range of the new radar. Although Charlotte would be a logical choice for an office, radar locations are subject to political influence. In 1995 the winning location for the new consolidated office was Greer, S.C., near the home of the powerful (and now deceased) Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C.

FEMA denies assistance

Within hours of the twister, assessment teams had completed preliminary damage inspections and a “Proclamation of a State of Emergency” was issued jointly by the City of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. The proclamation put the FEMA process in motion for requesting aid after a disaster. But less than two weeks after the twister, FEMA announced that Mecklenburg and Cabarrus counties were ineligible for federal disaster relief. FEMA uses a complex formula to determine eligibility based on dollar amounts of damage, the operating budget of the jurisdiction and the amount of individual insurance coverage in place where the incident occurred.

Bobby Smith, Cabarrus County’s emergency management director, said there must be a minimum number of severely damaged or destroyed homes within a single county to receive aid. The Harrisburg tornado’s destruction was not widespread enough, nor the damage figures high enough to be declared eligible for FEMA assistance. “We appealed the decision,” he said, “and additional federal assessment teams came out. But their assessment reaffirmed the original findings.”

According to Wayne Broome, Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s emergency manager, “with two jurisdictions involved, had one been eligible, for instance Mecklenburg County, FEMA would have automatically included Cabarrus County as an adjoining county, and vice-versa.” But neither county was declared eligible.

Without a disaster or emergency declaration, most damage claims were handled by individuals and their insurance companies. A year after the tornado, some damaged homes had reportedly been torn down, but most had finished, or nearly finished, repairs.

Lessons learned

Smith, the Cabarrus official, said: “Emergency management personnel from both counties, including fire, sheriff’s and police departments, were in constant communication in the days following the tornado, assisting one another whenever needed. However, we learned that establishing a joint command center would have been better,”

The lack of a warning from NWS remains a significant concern. The weather service office in Raleigh issued a warning for Stanly County, but neither Cabarrus nor Mecklenburg was warned.

As a result of the Harrisburg tornado, “Cabarrus County has a better, quicker, in-house assessment process,” said Smith. “We developed programs that tie together data from tax rolls, building permits and other sources to give our teams access to better data.”

The tornado also illuminated the need for more accurate numbers of total damage. “We now go door-to-door surveying damaged areas on the ground and inside buildings. Our teams include building inspectors, tax assessors and the fire department,” Smith said. Additional flights for aerial photography now provide more up-to-date images that can be used to evaluate pre- and post-event conditions.

Broome and Smith both urge residents to be prepared for emergencies. First, they recommend people get weather radios. “Developing a siren system in Charlotte would cost in excess of $50 million, plus another $5-6 million annually to maintain,” said Broome. “It’s just too costly for the public.”

“A tornado develops quickly, and is most often an isolated event,” Broome said. “Individuals become their own best safety net. They may know the situation the same time as emergency management personnel.”

UNC Charlotte does have sirens. The university rolled out its new emergency alert system last August. It includes five sirens on the main campus, which is near Harrisburg, plus scrolling text banners on nearly 1,000 plasma screens across the main and center city campuses, and direct messaging via text and email.